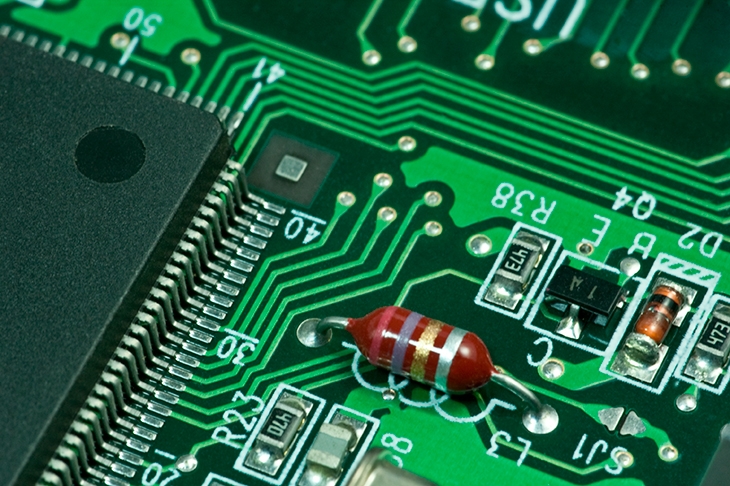

Just as the auto industry embraces the electric future I wrote about last month, it hits a new crisis: a shortage of the microchips that power everything under the bonnet. As a parable of globalisation’s perils, this one has all the ingredients from trade war to fire, drought and Covid pestilence.

When car production slumped last year, chip-makers switched to meet booming demand for parts for smartphones, tablets and laptops. Now car factories are keen to raise output again, but there aren’t enough chips to go round. The leading source, Taiwan, is entangled in US-China tensions and its factories are afflicted by water shortages; other plants have been stricken by fire (in Japan) or extreme cold (Texas). The result is that Ford, Toyota, Volvo and Volkswagen have paused production lines and Nissan’s Sunderland plant has blamed non-delivery of chips for a decision to put 750 workers back on furlough.

Maybe there’s a wider moral here. Cheap labour and just-in-time logistics have accustomed a generation of consumers to miracles of choice and affordability. But now we’re seeing what can go wrong in a supposedly ‘frictionless’ system: trucks gridlocked in Kent, containers stockpiled at the wrong ports, rotting food cargoes, shortages not only of chips but also of minerals needed for electronics, plus vaccine blockades — all point to continuing disruptions and rising costs. Dramatic swings in January’s UK export-import figures were dismissed by some pundits as a Brexit-meets-Covid blip. But they could be the harbinger of an era of fractured trade with ramifications for global prosperity we have yet to discover.

The dignity of ex-PMs

Should former prime ministers ever sully their hands in business? The question arises as the spotlight on the collapse of Greensill Capital swings to David Cameron — whose government appointed the Australian entrepreneur Lex Greensill to ‘sort out the whole supply-chain finance issue for us’ in 2014, and who was in turn hired, after leaving office, as an adviser to Greensill — and rewarded with stock options that might have made him rich if the company had achieved plans for flotation. In that role, Cameron reportedly contacted the Chancellor and the Bank of England seeking access for Greensill to the government’s Covid Corporate Financing Facility for major companies. The fact that his lobbying didn’t actually do the trick and no one is alleging wrongdoing is no impediment to opposition calls for him to be hauled in front of the Treasury select committee to explain himself.

If challenged as to whether his position in public life ought to preclude jobs that risk such embarrassment, he could of course cite Tony Blair’s ‘senior adviser’ title at JP Morgan Chase, Sir John Major’s corporate CV entries ranging from US private equity giant Carlyle to Credit Suisse and the National Bank of Kuwait, and even Gordon Brown’s brooding presence on the advisory board of the Pimco bond fund. But such connections always look a tad uncomfortable: ex-PMs should rest on their dignity — and the cushion of their speaking fees, memoir deals and parliamentary pensions.

Boom town

Talking to north-east business folk last week, I met scepticism in relation to Rishi Sunak’s flagship levelling-up gift to the region: the siting of the Treasury North campus at Darlington and the relocation of at least 750 civil servants from London. The town’s shops and trades will certainly benefit, while accounting and law firms are already chasing office space adjacent to what will become a hub for ‘critical economic departments’ from several ministries, including the Department for International Trade. But the first impact of the announcement, I’m told, was unhealthily speculative: a flurry of buy-to-let investors trying to snap up flats in the vicinity and at least one house seller, immediately after the Budget speech, demanding a £5,000 price hike from a first-time buyer.

Be what you’d rather be

Junior analysts at Goldman Sachs in London have been complaining about 98-hour average working weeks and habitual abuse by their seniors — though their ultimate boss, New York-based chief executive David Solomon, recently praised the investment bank’s ‘collaborative apprenticeship culture’ and dismissed lockdown working from home, which might have partially relieved the youngsters’ stress, as ‘an aberration’. Yes, being expected to work every waking hour under the lash of Goldman’s trading-floor slave-drivers is cruel — but hey, kids, that’s the dream job for which you beat a hundred other applicants, so don’t ask for sympathy.

And I speak from the heart, having taken too long to escape my own first career in investment banking, when I say that if you can’t hack it, get out and reinvent yourself as whatever you’d rather be. As a chef, a vicar, a vet or a start-up entrepreneur, you might still find yourself working 98-hour weeks — and at a fraction of the pay — but you’ll forever have the satisfaction of having raised two fingers to Goldman Sachs.

Strong drink

One answer to last week’s question about favoured suppliers of lockdown distraction and consolation was provided by Kingfisher, parent of the DIY chains B&Q and Screwfix, which reported a winter sales boom and a 44 per cent jump in annual profits. Likewise Lego’s building-set toys, popular with bored adults as well as children, registered a 21 per cent rise in consumer sales, while the FT reported a surge in demand for online MBAs.

This column’s readers tend more towards strong drink — praise for Master of Malt as a supplier and the Scotch Malt Whisky Society for Zoom-based tastings — but at least one of you sobered up for the National Gallery’s virtual exhibitions and lectures. I’ll report your foodie suggestions in next week’s Easter issue. More welcome, to martin@spectator.co.uk.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in