Disparate stories illustrate the free speech crisis roiling academe in many democracies. Pratap Bhanu Mehta, former head of the private Ashoka University and a trenchant, equal-opportunity critic of successive governments, resigned as professor when some university founders told him he’d become ‘a political liability’. Around 180 academics from several prestigious US and British universities registered their dismay in an open letter. An Aberdeen University student was banned from student union premises for posting ‘Rule Britannia’ to a webchat: such subconsciously racist language can trigger sensitive students from countries once ruled by Britain. So why would they choose to study in racist Great Britain? Queensland University’s Chancellor Peter Varghese told a Senate inquiry in March that anti-China student activist Drew Pavlou had ‘painted himself as a victim and the university as a villain’. The University of Tasmania allegedly refused to publish a paper by the UQ law dean that departed from transgender orthodoxy. ‘An Apology to J. K. Rowling’ by Melbourne University’s Petra Bueskens was the most read and shared Areo magazine article last year. When the Australian Sociological Association tweeted congratulations, some members accused it and her of transphobia and they deleted the post with an apology.

Universities are the crucibles of ideas. Democracy dies without open debate, viewpoint diversity and robust contestation of ideas. Universities flourish in conditions of free inquiry, critical interrogation, intellectual integrity and firewalls against donor and political pressure. Have they instead become the chief enablers of the long march through institutions? The death in December of James R. Flynn of the ‘Flynn effect’ fame (and my boss at Otago University for 16 years) warranted feature articles in the liberal New York Times and the conservative Wall Street Journal. His last book, In Defence of Free Speech: The University as Censor, was promoted by Emerald Press in 2019 but then pulled on legal advice, picked up by Academica Press in the US and published as A Book Too Risky To Publish: Free Speech and Universities.

For nine years, with Kofi Annan’s backing, I helped protect the institutional autonomy and academic integrity of the UN University, little knowing that reputable Western universities would demonstrate a softer commitment to core university values in the age of microaggressions, trigger warnings and emotional safe spaces. These have transformed the university’s mission from challenging ideas to coddling snowflakes. Academics being de-platformed, cancelled, censured, disciplined, fired and disinvited has become commonplace. Management-speak administrators cower before Twitter, mistaking volume of noise for breadth of support, genuflect to woke fads and are keener to regulate behaviour than defend intellectual freedom. Academic freedom in the UK: Protecting viewpoint diversity had depressing findings: 75 per cent of academics vote for left-leaning parties; there’s ‘widespread… discrimination on political grounds in publication, hiring and promotion’; just 37 per cent are comfortable sitting next to advocates of gender-critical feminist views; and many choose to self-censor for fear of consequences. Civitas too found that over one-third of British universities are very restrictive and half are moderately restrictive on free speech curbs. In Canada and the US, similarly, 40-45 per cent of academics would not hire a Trump supporter. US-sourced Critical Race Theory has been embraced by Universities UK.

The full force of stifling intellectual conformity and punishment of scientific dissent has been felt by critics of Covid lockdowns. Martin Kulldorff of Harvard Medical School wrote: ‘Among infectious disease epidemiologists that I know and interact with, the majority is in favor of an age/risk-targeted strategy of focused protection. For various reasons, some have been uncomfortable speaking out publicly.’ The most egregious example is that of Scott Atlas, a Stanford professor vilified for serving as a Covid adviser to Trump. In an open letter, 98 Stanford colleagues accused him of ‘falsehoods and misrepresentations’ without listing any, making refutation impossible. Fortunately, the President and Provost publicly defended academic freedom. Atlas gave his version of the controversy in a recent lecture. The absence of any hint of embarrassment or shame by those engaged in mob bullying and calls for censorship is striking.

There are some green shoots of resistance. Last year the Free Speech Union intervened successfully to overturn several instances of de-platforming gender-critical speakers at Oxford and Cambridge dons overturned, by a 1,316-162 vote, the effort by administrators to ‘be respectful of the diverse identities of others’. In December, a Court of Appeal ruled that ‘free speech encompasses the right to offend, and indeed to abuse another’. In February the government published a white paper on higher education that prioritises intellectual freedom over ‘emotional safety’. At Toronto, a mob of woke students, relying ‘entirely on intellectually dishonest forms of character assassination’, failed to have Arjun Singh’s scholarship rescinded.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, Heterodox Academy, Academic Freedom Alliance and project ‘DivestU’ are initiatives to combat free speech threats on US campuses. Students at Chicago – the university that gave us the Chicago Principles – launched Critical Thinker, an online journal, demanding that educational experience should ‘rigorously confront and challenge our most deeply-held beliefs’. When Prof. Jonas Ludvigsson of Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute quit research on Covid-19 because of abuse and harassment, the government strengthened protections for academics against ‘cancel’ campaigns.

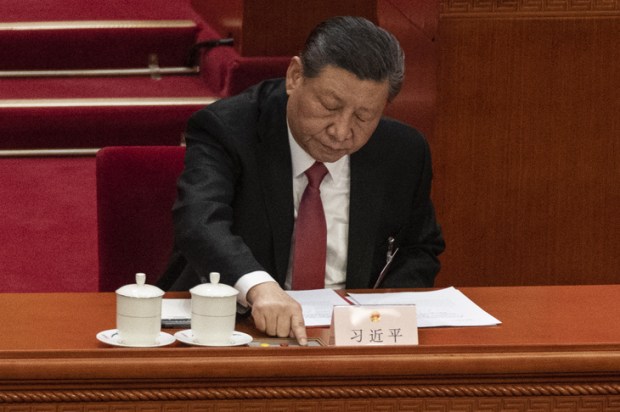

To paraphrase Churchill on Munich, faced with a choice between fighting for principle and dishonour, many universities choose dishonour and get a fight. The High Court decision to entertain Peter Ridd’s appeal against James Cook University indicates that bigger issues of public importance – can academic freedom be enfettered by workplace codes of conduct? – will be adjudicated. In the scramble for overseas student fees and institution-building grants, vice-chancellors can be seduced by Chinese money. Even when some are embarrassed into resigning from one university for having been insufficiently attentive to academic values, they might still be courted by others desperate for leaders with a proven track record of large-scale fundraising and less regard for institutional integrity.

A respectable university should have bottom lines that do not collapse into only the bottom line. University leaders must have the experience and judgment to tell the difference between the two, a moral compass to help navigate these treacherous waters, and the character to act on convictions.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in