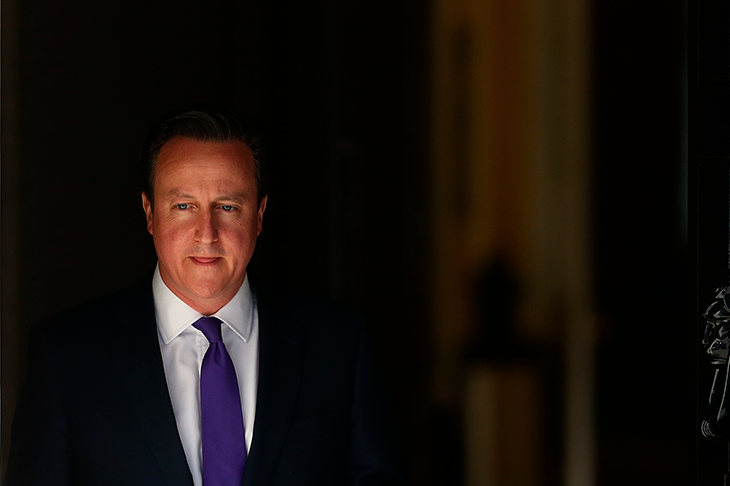

Ex-prime minister David Cameron, ignoring official protocol, though not acting illegally, went directly to the chancellor Rishi Sunak to ask him to give Greens(w)ill Capital access to government-backed loans. Result? No cigar. And that is ‘corruption’? Tell that to the ancients.

For Greeks and Romans, one of the oils which kept social, political and business wheels rolling was reciprocal gift-giving. But how does one draw a line between a ‘gift’ and a ‘bribe’? Those claiming a gift was a bribe would talk of ‘corruption’ or ‘buying’, ‘selling’ and ‘profit’ (trade was seen as a dirty business); those defending it as a gift called it ‘giving’, ‘receiving’ and ‘persuading’. Indeed, so common was bribery that the Greek comic poet Cratinus (519-422 bc) invented its three mock goddesses: Doro, ‘St Give’, Dexo, ‘St Receive’ and Emblo, ‘St Backhander’.

The point is that both public and private benefit could be at stake in a ‘donation’ (bribe or gift). The Greek orator Hyperides (c. 390-322 bc) claimed that Athenians actually encouraged statesman and soldiers to make large ‘personal profits’ from ‘donations’, provided they were ‘used in the public interest, not against it’. Democritus (5th century bc) argued that there was nothing like the rich giving ‘donations’ to the poor to produce concord that strengthened the community. Romans admired wealthy men who put their money to good use: ‘bread and circuses’ were a form of ‘donation’. What about ‘donations’ at election time? Latin ambitio meant ‘going around seeking votes’; ambitus, from the same root, meant ‘bribery’.

Back, then, to Greens(w)ill. No bribery was involved, though Cameron’s interests were; but so it is with all business lobbying. Whatever the wider implications across government, the issue is that Cameron saw nothing even mildly whiffy about his private approach. One wonders why Sunak did not tell him to join the queue. Publius Rutilius (b. 158 bc) would have. He once refused a friend’s unjust request. The friend said: ‘What good is your friendship to me if you don’t do what I want?’ Rutilius replied: ‘And what good is your friendship to me, if I have to act dishonourably because of it?’ Ah, honour…

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in