The last thing Mars needs is Communism.

When the Zhurong rover landed on Mars in May 2021, it created a state of panic amongst the other rovers. Aggressively named after the god of fire, Zhurong ruthlessly tracked down NASA’s rovers and set about collectivising them by spray-painting their exterior casings red against their will.

Just kidding.

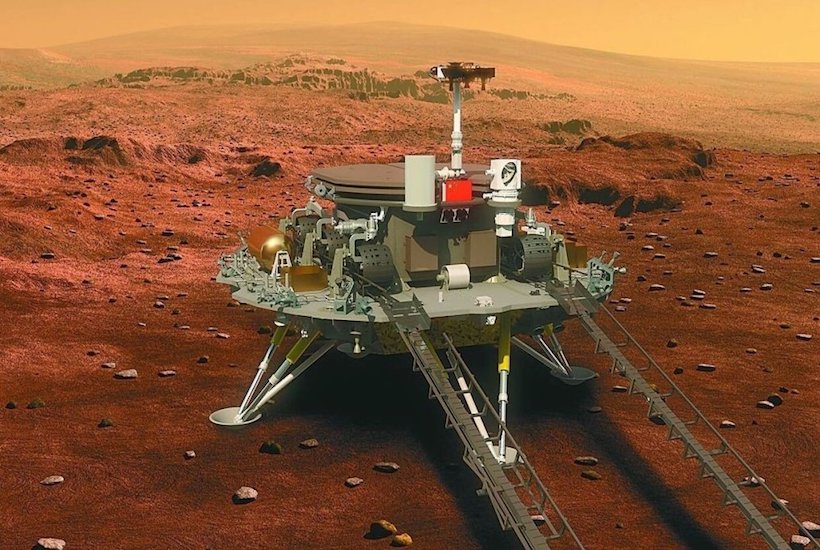

Zhurong, like the Chinese Communist Party who created it, is an anti-social creature. Its Twitter presence is run by fans instead of the government, and the details available on its mission are sketchy at best. It forms part of the Tianwen-1, China’s interplanetary mission run by the China National Space Administration. As with the rest of its robotic brethren, its mission is carefully named. Tianwen roughly translates to the ‘quest for heavenly truth’ in mimic of the other lofty names given to bits of metal flung at the stars.

Upon its landing, Xi Jinping announced, “You were brave enough for the challenge, pursued excellence and placed our country in the advanced ranks of planetary exploration. Your outstanding achievement will forever be etched in the memories of the motherland and the people.”

While all the other rovers chat continuously with each other on Twitter, the new arrival is somewhat of an outsider and likely to remain so under the watch of its secretive parent. Part of this stems from the cultural practice of the Chinese to only release information upon confirmation of success. The American rovers livestream, which means that the full struggle of space exploration is played out on the global stage, including failures (like crashing your $327 million Climate Orbiter after forgetting that the rest of the world use the metric system).

Still, Zhurong survived the journey and will remain in the giant Martian sandpit, mucking about with the other rovers as a member of their extended family.

What does Mars mean for humanity and why are we all so keen to spend billions getting there? It’s like an arms race of glorified toy cars.

In the late 90s, the world re-lived its space fetish with the first Mars rover digging its wheels into the dirt. After the initial buzz of excitement, the exploration of Mars matured into a tame affair, with the occasional headline about water or potential life lurking in the dust.

Humans have become a little more relaxed about space, but many of us paused in wonder when time-lapse colour images showed dust-devils spiralling across the surface, breaking our vision of Mars as a static idea. They were later accompanied by an actual recording from Mars. The hollow scratch of wind sobered us to the reality that these distant worlds are truly alien.

Mars has been a slow burn compared to the instant gratification of the Moon landing, but it will have its globe-stopping moment when a human puts boots on the ground. Until then, it remains a planet inhabited entirely by robots. They rut around in the dirt, eke out a living from their distant sun, and check in on each other from orbit. In 2021, they even post selfies to prove to their anxious parents at Mission Control that they are alive and well.

When they dig a hole, we are proud of them. When they settle in for the winter, we fret. These robots have become humanity’s children. They go where humans cannot and in turn, we live vicariously through them.

The first Martian rover was named Sojourner, after the African-American and women’s civil rights advocate Sojourner Truth. This poor little rover was more of a crash test dummy, sent out to dip its toe in the water. It was, without question, the bravest.

Spirit and its twin Opportunity were the first true explorers. They made the most of their slightly awkward landings and headed off into the craters and sand traps looking for water. It was around this time that the world’s major religions started to panic a little bit, coming up with official action plans in case either of these two robots did something inconvenient – like discover alien life. It was the first hint that Mars might not just be a passive scientific achievement like the Moon, but humanity’s first serious social test since it discovered that it was not the centre of the universe.

If Mars turns out to be a world that housed its own menagerie of life, how is humanity going to shuffle its view of existence? Did Mars have gods and dreams of its own?

Poor little Spirit eventually froze to death, setting itself to sleep one winter. While it is possible that it is still alive, deep in hibernation and waiting for someone to wake it up – NASA may never know its true fate, just like all those great explorers lost at sea.

Opportunity’s last words reached us on February 17th 2019. ‘My battery is low and it’s getting dark.’ He was meant to live for 92 days, but made it to the grand old age of 5498 days. Before signing off forever, NASA played Opportunity a lullaby, ‘I’ll Be Seeing You’ by Billie Holiday. He, along with his robotic friends, will spend 4 billion years waiting for the sun to fade.

Curiosity has been a much larger undertaking, literally and figuratively. Clocking in at the size of a car, he is kitted out to search specifically for water and life. Curiosity has been rolling around for 9 years, checking stuff out. His name was selected by 12-year-old Clara Ma, whose winning essay stated:

Curiosity is an everlasting flame that burns in everyone’s mind. It makes me get out of bed in the morning and wonder what surprises life will throw at me that day. Curiosity is such a powerful force. Without it, we wouldn’t be who we are today. Curiosity is the passion that drives us through our everyday lives. We have become explorers and scientists with our need to ask questions and to wonder.

It is such a shame that today’s children are cultivated in an environment of fear. They have been coached to treat science as a system of immutable absolutes rather than the endless inquisition of the universe’s secrets. If we let them name missions we would probably end up with I-Can’t-Breathe 2.

When Perseverance landed in 2021, it immediately did the Millennial thing and snapped a photo, tweeting out, ‘Hello, world. My first look at my forever home.’ Its much older sibling, Curiosity replied, ‘Bots before boots. So proud of you.’

Perseverance even brought a little helicopter along for company called Ingenuity – which looks a bit like the product of a night full of regrets between a mosquito and a solar panel. It contains a token piece of fabric from the wing of the Wright Flyer – the 1903 Wright Brother’s aeroplane that completed Earth’s first controlled-powered heavier-than-air flight. The area in which Ingenuity took its maiden flight on Mars is named Wright Brothers Field in tribute.

Indeed, the whole planet is littered with the sentimental fragments of human civilisation. It is something humans have done since explorers named new lands with memories of their loved ones. In a way, it helps to familiarize the terror of the unknown. Perhaps we do this because it is harder to fear a frightening vista if it is named after the things that bring us hope.

The way humans explore reveals that we are overwhelmingly a nostalgic species, steeped in affection and humour.

Our rovers are lone explorers on a dying world, but they represent something intangible about humanity – a truth that we feel rather than understand.

The arrival of a Communist nation, and potentially a global aggressor back on Earth, challenges our belief in the neutrality of space exploration and our ability to maintain unity on the frontier of discovery.

Will humanity come together at the fringes of survival, or will Mars become a deadly competition of national ego?

Watching ourselves on the Moon was proof that we could dream beyond our cradle. Of course, when we started planting flags, bureaucracy was forced to catch up by drafting The Outer Space Treaty. Simply put, it means that no one can ‘own’ the Moon – regardless of how many flags are stuck in the ground. It is set up as ‘the province of all mankind’, but if history tells us anything about humans, it is that this era of peace will not last.

Reading the 17 articles of the declaration provides an honest snapshot of humanity. Article 4 bans nuclear arms and weapons of mass destruction while Article 5 follows up, re-iterating that activities are to be ‘peaceful’.

The declaration’s paranoia makes us sound like a bunch of space pirates. Maybe that’s why none of our interstellar neighbours drop in for a visit.

Either that, or they think we are a race of robots.

Alexandra Marshall is an independent writer. If you would like to support her work, shout her a coffee over at Ko-Fi.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in