Last week’s by-election result in Chesham and Amersham was a slap in the face for Boris Johnson. Fortunately it was a figurative one, unlike the punishment dished out to Emmanuel Macron by a disgruntled voter the previous week during a presidential walkabout. But it’s the fate of Macron’s predecessor in the Elysee that should focus Conservative minds in the wake of their chastisement in Chesham.

A decade ago, François Hollande was in the early stage of campaigning for the 2012 presidential election. He styled himself as ‘Monsieur Normal’, a welcome contrast to Dominique Strauss-Kahn, long tipped as the man who would lead the Socialists to victory in the election. That was before he disgraced himself in a New York hotel room in May 2011.

That same month a left-wing think-tank, Terra Nova, published an 88-page report detailing how the Socialist party might win the election. Among its conclusions was that:

‘The France of tomorrow is above all united by cultural and progressive values. It wants change. It is tolerant, open, optimistic and inclusive…it is opposed to an electorate that defends the present and the past against change.’

One current affairs magazine summed up the report as: ‘When the left said farewell to the workers.’

Not that it seemed to harm Hollande. In May 2012, he became the second Socialist president of the 5th Republic, and how the left celebrated. I had been out for supper in central Paris on the evening of his victory and my metro ride home took me through Solférino, then the HQ of the Socialist party. Hundreds of Hollande’s supporters piled into the metro, singing, dancing and cheering. Overwhelmingly they were young, white, middle-class metropolitans and, mon Dieu, were they glad to be rid of Nicolas Sarkozy.

So was the majority of the country. The brash, strutting Sarko, president Bling-Bling as he was known, was not a popular president and Hollande was seen as a refreshing change. He enjoyed a 61 per cent approval rating on entering office, and it wasn’t hard to understand why. He was a ‘Hail fellow well met’ sort of chap, a man who evidently enjoyed his food and his drink. He was nicknamed ‘flamby’ because of his resemblance to a popular small wobbly pudding in France.

Hollande also had a weakness for women, which further endeared him to voters who saw in him a little bit of themselves. Hollande doesn’t fit the stereotype of the drop-dead gorgeous Gallic lover but apparently humour was his strength as a seducer

He fathered four children with a fellow Socialist MP, Ségolène Royal, before leaving her in 2007 for a glamorous journalist eleven years his junior called Valérie Trierweiler. Not long into Hollande’s presidency, Royal and Trierweiler had a ‘spat’ on Twitter, what the French press called ‘Trierweilergate’. The latter came out worse and she never recovered her reputation. She came to be seen as meddling and self-absorbed, a distraction for the man charged with running the country.

Eventually Hollande tired of her, ending their relationship in January 2014, by which time he had taken up with an actress called Julie Gayet, who was eighteen years his junior. Even now, Trierweiler is still hurting; on a radio show last week she mocked her former beau as ‘small, fat, ugly (and) bald’.

When Hollande and Gayet became an item, his presidency was already in trouble. It turned out that the think-tank was wrong: France was not hankering after change, nor was it united by ‘cultural and progressive values’ espoused by the government. Hollande didn’t care. He was going ‘woke’ and if his core voters didn’t like it, well, they could lump it.

In the first two years of his presidency the priorities were the gay marriage and adoption bill – which achieved the rare feat of uniting conservative Muslims and Catholics – and climate change, culminating in the Paris Agreement of December 2015.

In contrast to his energy and determination in championing those two issues, Hollande was lacklustre in confronting the immigration crisis of 2015 and the wave of Islamist terrorism that erupted in the same year. He was aware of the growing cultural tensions in France, what privately he described as the ‘partition’ of French society. But he was too weak and timid to do anything about it, passing on the problem to his successor.

As for Hollande’s economic policies, they turned France into a laughing stock, as unemployment grew to nearly 11 per cent, and the prime minister, Manuel Valls, was despatched to London in 2014 to plead with the British to stop their ‘French bashing’.

The upshot of Hollande’s indifference to his ‘Red Wall’ supporters was the disintegration of the Socialist party vote in the 2017 election. Hollande didn’t even put himself forward as a candidate because he knew the outcome would be a humiliating rejection. The polls had shown him that; by the end of his presidency his approval rating had fallen from 61 per cent to an unprecedented 22 per cent, making him even more unpopular than Sarko. Monsieur Normal had become Monsieur Nauseous, and the voters were sick of the sight of his grinning geniality.

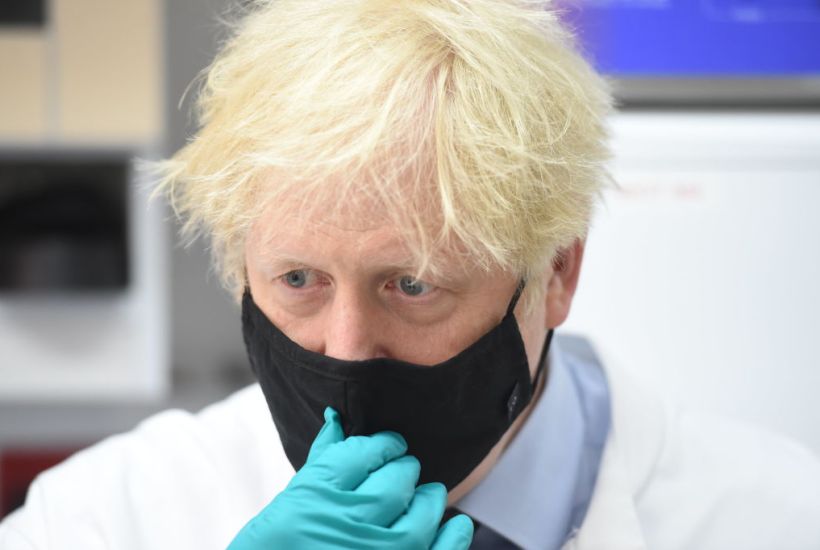

Boris Johnson should take note of François Hollande’s fate. The pair have much in common: their affable but weak characters, their short and stout physiques, their tangled love lives, their eye for a younger woman; the cynic might say their politics, too, what with the Prime Minister risking the ire of traditional Tory supporters with his Green Industrial Revolution and the ‘gender-neutral and feminine’ post-Covid world that he sold to G7 leaders this month.

Meanwhile Boris has remained largely silent over the last year as the culture wars have played out. While there have been attempts to defame Britain’s history and heroes, including his own, Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister has done precious little to speak up for those Brits who are fed up with such attacks.

Last week’s disastrous by-election result in Chesham and Amersham should serve as a warning to Johnson. If you betray your base, if you take their support for granted, then they will turn on you, and your bonhomie will count for nothing at the ballot box.

<//>

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in