Back to the Globe after more than a year. The theatre has zealously maintained its pre–Covid staffing levels. On press night, there were eight sentries patrolling the forecourt where just 42 masked spectators watched a revival of Sean Holmes’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The Globe describes his show as ‘raucous’. The action is set in a forest near Athens during the classical era but the text uses 16th-century English. So it seems crazy to add a third time zone but most directors do so unquestioningly.

This modernised production features an array of multicoloured stylings inspired by funfairs and Caribbean carnivals. The palette is a mad rainbow of acid pinks, savage yellows, eye-stabbing greens and brutal scarlets. Several costumes seem to have been made out of Liquorice Allsorts glued to strips of fabric. A few of the garments are attractive, in an over-the-top fashion, but the relentless barrage of colour overwhelms the text of this delicate and absurdly over-complicated drama. Only a viewer who knows the story backwards will derive much pleasure here. And the cast of 11 are obliged to play more than 17 parts, which makes for some awkward doubling.

Extra snags have been added. Titania enters wearing a cap marked ‘Queen’. Beside her comes an attendant, disguised in a turquoise burqa, who holds a parasol embroidered with the word ‘Titania’. Experts will know which is the real character. Newcomers will be mystified. The role of Puck is shared by half a dozen players in T-shirts identifying them all as ‘Puck.’ The last thing this play needs is a fresh layer of encryption.

In a famous scene, Titania is duped by Oberon into falling in love with a donkey but the animal’s costume is an attractive confection of pink, saffron and lavender. The couple look rather sweet together so the cruelty of the prank is lost. Then Oberon feels a pang of remorse. ‘Her dotage now I do begin to pity,’ he says. It sounds meaningless.

The rude mechanicals, as usual, lay on a strain of anti-comedic comedy which is painful to watch. On the upside, the excellent music is delivered by a terrific brass and woodwind ensemble. The best moments arrive when the actors go off-piste and banter with the crowd. A Dutchman in the forecourt was recruited to play a cameo role. That was fun. A punctured sun lounger got a good laugh. Titania hid herself in a massive wheelie bin out of which she climbed with great difficulty. ‘I can do Parkour,’ she quipped. It’s strange to see a Shakespeare play whose best features have nothing to do with Shakespeare.

Villain in Tinseltown is adapted from the memoirs of George Sanders. We meet the Hollywood star in his dressing room during the making of a rubbishy Roman epic in which he plays a heartless baddie with an upper-class English accent. ‘I’m a drifter,’ he says, ‘who drifted into fame.’ He asks himself a question. Everyone in the world wants what he has, so why doesn’t he? Some of his self-directed barbs might have been written by Noël Coward. ‘An actor is a muddle–headed peacock chasing after the rainbow of his own narcissism.’

Sanders killed himself at the age of 65 — one of his suicide notes read ‘I’m leaving because I’m bored’ — but he seems not to have suffered from a mental disorder other than pathological cynicism. ‘I defy any producer to send me a good script.’ He made about five films a year for decades, most of them forgettable. He didn’t mind being typecast because he was lazy and proud of it.

His role as a scheming theatre critic in All About Eve won him an Oscar but the prize brought no boost to his earnings. ‘Hollywood admires people who win awards but hires people who make money.’ All About Eve failed at the box office, as he points out, because the characters were unpleasant and the film-going public doesn’t care about ambitious, wrangling thesps. He was briefly married to Zsa Zsa Gabor whom he described as, ‘champagne… I had to keep up with her standard of effervescence’. Towards the end he likened himself to ‘a crumbling 13th-century castle that survives by being viewed’.

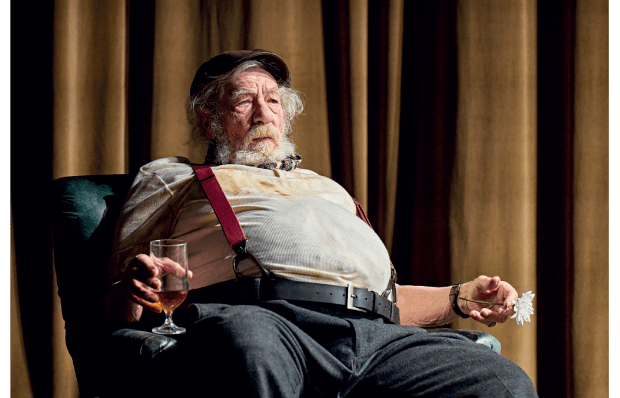

This show offers a wonderful insight into a complex, creative and highly intelligent man who was scathingly honest about his selfish, amoral character. Jonathan Hansler plays him with some strange visual touches. He’s unshaven and his reddish hair seems to have been attached to his scalp with lard. But he’s superb at capturing the spirit of Sanders, the languid bitterness, the elegant froideur. As he prowls the stage he adds a hint of campness and creepiness too. What he can’t get is the smoky, purring, sinister voice. That would require an impersonator. Sanders might be a good subject for a Steve Coogan biopic. But although he’s fascinating to study, he’s very hard to love.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in