The years after the first world war were a boom time for utopian communities. As the survivors of the conflict began to recover, many were drawn towards experimental ways of living. Anna Neima looks at six of these communities, asking what brought them together, what kept them going and what legacy, if any, they left behind. In doing so, she offers an original perspective on the entire period and a new way of navigating its artistic and ideological upheaval.

She begins with Santiniketan Sriniketan, the community founded by the Nobel Prize-winning poet Rabindranath Tagore in West Bengal. Part ashram, part school, part agricultural college, it promoted the twin causes of educational reform and rural regeneration, and went on to influence countless other communities. It also established a pattern of sorts, with a charismatic leader and devoted disciples; a remote setting and uncomfortable accommodation; a mix of ancient wisdom, political radicalism and alternative therapy, along with failed attempts at self-sufficiency and a constant shortage of cash. This pattern is repeated by almost every one of the book’s communities, yet thanks to Neima’s rigorous research, each chapter offers something new.

The most interesting figures were usually the founders, typically idealistic men and women from comfortable backgrounds, who were good at starting social movements but less suited to communal life. Alongside Tagore we meet Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst (she an American heiress, he a failed priest turned trainee agronomist) who started Dartington Hall in Devon. Then there was the Russian mystic George Gurdjieff, who set up the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in the forest of Fontainebleau; the Japanese author Saneatsu Mushanokoji, who began the Atarashiki-mura community on Kyushu island; and the polymath Gerald Heard, who established Trabuco College in the foothills of California’s Santa Ana Mountains.

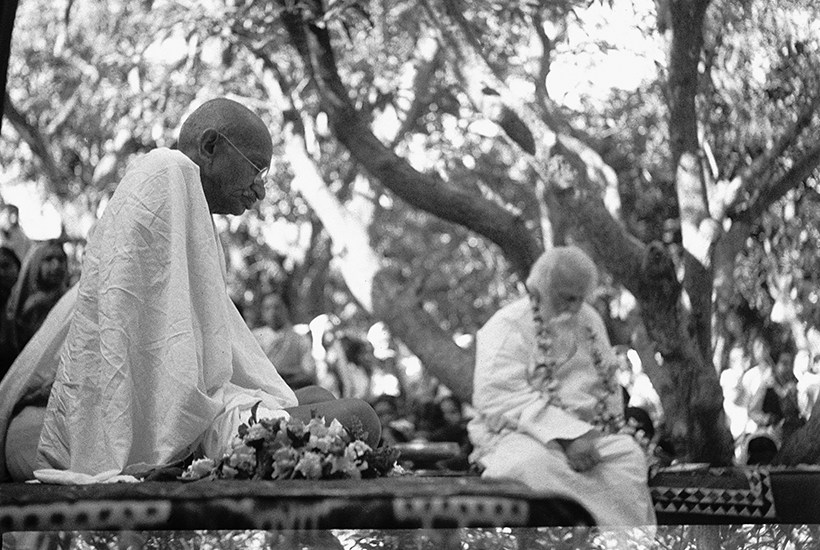

It’s also interesting to learn about the artists, writers, politicians and thinkers who were drawn towards these communities over the years. Ramsay MacDonald and Oswald Mosley both visited Santiniketan Sriniketan, as did Gandhi, while Dartington Hall counted Aldous Huxley, Roger Fry, Vita Sackville-West and W.H. Auden among its guests, along with an entire ballet company in flight from Nazi Germany. Most dramatically, Katherine Mansfield joined Gurdjieff’s community in the last year of her life, watching the sacred dancing from her sickbed.

Neima’s respect for these men and women is clear, though her tone is never pious and her approach never sentimental. She takes seriously their attempts to rebuild society, while also capturing the absurdity of community life. She also understands how eccentric these communities must have seemed to outsiders — such as Mushanokoji’s collective in the mountains of Japan, where ‘a group of intellectuals from Tokyo… attempting to redeem global humanity by farming was so bizarre that it seemed unhinged’. In fact, much of the book’s comedy comes from the contrast between the movements’ lofty aims and the mundane, even amateurish, reality — like the spoilt young visitor to one communal farm trying to make the place look more picturesque by giving away all the manure, unaware that it might be used as fertiliser.

The background of political unrest makes these efforts much more poignant, especially for the Bruderhof community in Germany. This group was founded in 1920, hoping to set a peaceful example to the rest of the country by living in Christian brotherhood. Of course they were powerless to prevent the coming war, and in one of the book’s most moving passages we learn how this collection of Protestant pacifists were treated as communist dissidents by the Gestapo, with several members taken to camps and the rest forced to flee. However, the Bruderhof managed to outlast the Nazi regime, and now boasts some 3,000 members in 26 different communities spread around the world.

The most durable communities often share a religious foundation, which can remain intact long after their founders’ deaths. That said, the rest of the book’s communities also survive in some form, though few would be recognisable to the original members. However, survival is not the only way of measuring their influence, and perhaps they matter more as symbols, the proof that other forms of existence are always possible. Or, as Neima writes towards the end: ‘While few practical utopias last for long, utopian living is extraordinarily generative.’

It’s a convincing conclusion, and I finished the book with only one complaint: the accounts of the first and last communities seem thinner than the rest and the narrative less clear. The positioning of these chapters makes sense chronologically but it weakens the overall impact. However, there are still plenty of fascinating stories here, and by showing how a global crisis can lead people to question tradition and reshape society, the subject remains important to this day.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in