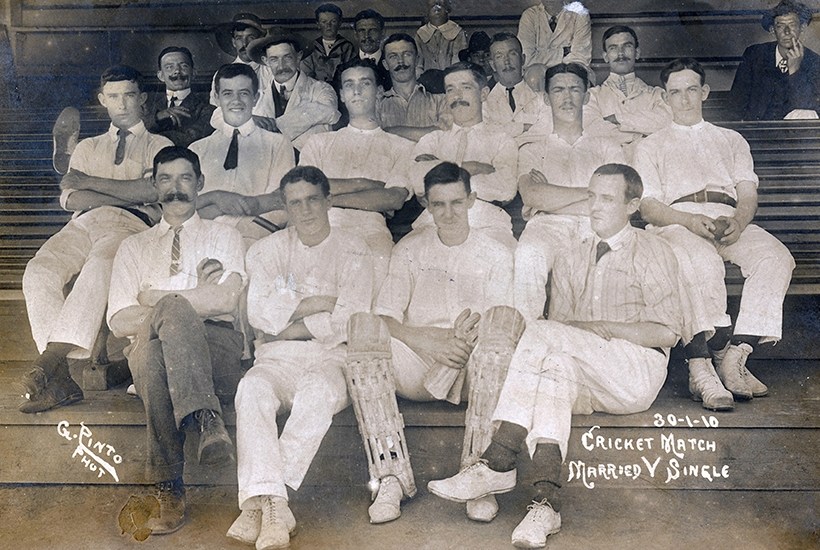

Cricket in Latin America sounds like an oxymoron. Yet in almost every country in the region willow was hitting leather before feet were kicking pigs’ bladders. England vs Australia, first played in 1877, may be cricket’s iconic series, but the Ashes cedes ten years of history to the contest between Argentina and Uruguay — the rivalry of the River Plate.

In Evita Burned Down Our Pavilion, James Coyne and Timothy Abraham, cricket journalists with a fondness for Latin America, travel from Mexico to Argentina with bat in rucksack and dates with fusty archives. A social history with elements of travelogue, the book tells a story of new horizons and false dawns, as the most English of pastimes tried to drop anchor amid scorpions, populist regimes and general bafflement.

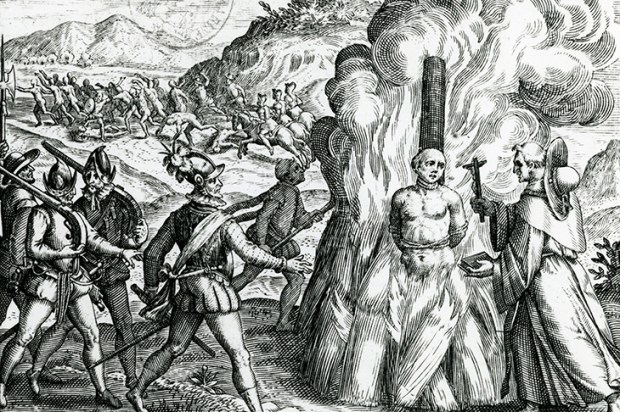

Despite the head start, England’s summer pastime didn’t catch on. In contrast to association football, the Victorian pioneers of cricket in Latin America were more concerned with preserving the game’s quixotic mores than expanding the franchise beyond fellow expats and the local elites, many of whom played at English boarding schools. Not even imperial patronage in the mid 19th century — by Brazil’s emperor Pedro II and Maximilian of Habsburg (he of the execution painted by Manet) could solidify cricketing foundations. Cricket grounds became football stadiums and, with a helping of Yankee neo-imperialism, baseball won the battle for the Caribbean. And in 1947, when Buenos Aires CC (est. 1864) refused to acquiesce with Eva Perón’s sweeping social schemes, she had the pavilion set ablaze.

Fires are not uncommon at Latin American cricket grounds, but they usually serve a more sporting purpose. To dry the wicket after tropical rainstorms, players light kerosene on the venerated strip. Try it yourself the next time some aquaphobic umpire stops play for rain. When the skies clear, Latin America’s cricketers enjoy some of the most distinctive playing conditions in the world. It’s a region where players can go out to bat applauded by the opposition but jeered by howler monkeys. By the sound of it, neither St John’s Wood nor Cape Town can match El Salvador’s El Quequeisque for beauty. Overlooking the Pacific ocean and flanked by a volcano, players and spectators can pick cacao buds from the trees and find shade under the coffee shrubs and jacarandas.

In such pristine settings, Coyne and Abraham meet flamboyant cricketing characters such as Phillip Barkhuizen, a South African who plays beside the jungle in Cancún. ‘In there are snakes of all different colours, panthers, pumas and animals you wouldn’t see in the zoo,’ Barkhuizen says, pointing beyond the boundary. ‘You can even get a crocodile straying from the lagoon. There is a four-step rule. If you can’t see the ball within four steps you give it up for lost. Or send in someone disposable.’ No wonder: Cancún (or ‘Kaan Kun’ in the original Maya) means ‘nest of snakes’.

Happier in a state of nature was Warwickshire’s all-rounder of the 1980s and 1990s, Paul Smith, who was sacked from his role as the professional at Buenos Aires’s Hurlingham Club for presiding over training dressed only in Speedos. Smith also hung out in the city’s nocturnal establishments with a fellow named Pablo Escobar.

Escobar reappears in the book as the biological father of Phillip Witcomb — a Colombian adopted by an MI6 agent. Witcomb, who boarded at Lucton in Herefordshire, was a handy wicketkeeper; which is to say, a picaro:

I was always looking to use sneaky little cheats to get batsmen out in school games. My favourite trick was using a piece of thread and matchstick under the bails, which I’d pull, and then we’d all celebrate a player being bowled. It must have been my Colombian genes.

Evita Burned Down Our Pavilion is full of diverting titbits: Pope Francis has a hand-crafted bat in his office, Jonners kept wicket for the State of São Paulo, and Rio’s cricketers joke that the statue of Christ the Redeemer is signalling a wide. But the humour and the editorial asides regularly stymie the innings. Short histories and episodes make the book feel staccato. The story of Mrs Perón’s pyrotechnics, which only runs to a few pages, is representative.

At the same time, the book sprawls like a Latin American megalopolis. The length of the acknowledgements section demonstrates Coyne and Abraham’s dedication, meticulous research and humility before their subject.

The book is a serious social history, sprinkled with cliché-free travel writing. However, like cricket’s 19th-century evangelists, the authors’ mission may be ill-fated. Apart from the eye-opening trivia, Evita Burned Down Our Pavilion will mainly interest professional historians of sport in Latin America. Cricket badgers may find the book too Latin American. Enthusiasts of Latin America will probably find it too cricketing.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in