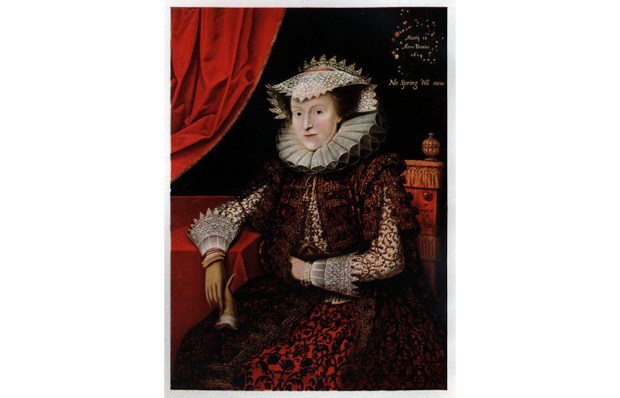

When Caroline Sheridan married George Chapple Norton in 1827 she ceased to exist. According to the legal status quo, as a wife she no longer had any rights separate to her husband. He could abuse her, claim her work as his own, spend her earnings and prevent her from seeing their children — and still be on the right side of the law.

The Case of the Married Woman is the third book in Antonia Fraser’s unofficial trilogy about the major legal upheavals of the 19th century. The previous two volumes have dealt with the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1829 and the Reform Act of 1832 — both turning points in the understanding of individual rights. This volume is necessarily more diffuse, since Caroline Norton’s campaigning for the rights of married women resulted in more incremental changes.

Caroline was the granddaughter of the Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan and the middle of three sisters celebrated across London as the ‘three graces’. Although her husband was only the second son of a baronet, as a barrister and a Tory MP he could at least provide the position in society that Caroline craved. Whig politics were in her blood and the Nortons’ home at Storey’s Gate in Westminster soon became a favoured salon of the political elite.

In this new study of Caroline’s life, Fraser takes care to sketch the character of her subject prior to the great tragedy that would come to define her. All of the Sheridans had ‘a whiff of the stage about them, along with an impressive reputation for brilliance,’ she writes, and Caroline was no different. A published novelist before her marriage, she specialised in sparkling conversation and ‘romantic teasing friendships’ with high-profile men.

As Fraser makes clear, however, the charming laughter didn’t always continue once the guests had departed. Norton was physically abusive to his wife, at one point assaulting her so violently that she had a miscarriage. They argued about their lack of money and the fact that Caroline had the higher earnings: ‘I made more in a month by writing than [Norton] did in a year as a barrister,’ she later recalled.

The tipping point came in 1836. Caroline was preparing to leave her husband and take her children, but he preempted her plans and bundled the three boys away in a carriage. She left anyway, and tried to support herself with her writing, while Norton used the courts to enforce his entitlement as her husband to her copyrights and earnings. In a move typical of her daring and courage, Caroline responded by running up debts all over the city. She informed her creditors that since she had no right to her own income or property, they must go to her husband for their money.

William Lamb, Viscount Melbourne, had been a frequent visitor to Storey’s Gate and although 30 years Caroline’s senior was her friend and regular correspondent. Her husband had initially profited from this relationship, encouraging his wife to use the connection to secure him an appointment as a magistrate and the right to be referred to as ‘Honourable’. After their separation, however, Norton attempted to blackmail Melbourne — who was now prime minister — alleging that there had been an affair.

Melbourne refused to pay the £10,000 demanded (around a million in today’s money), so Norton sued him for ‘criminal conversation’ with his wife. With divorce only available to a rarefied few via a special Act of Parliament, this action was the common remedy for adultery at the time. The nine-day trial caused a sensation and the judge ultimately decided in Melbourne’s favour; but as Fraser is careful to note, this victory had little impact on Caroline’s situation. Estranged but still married, she had no access to her children or right to the money she earned.

Rather than retreating into obscurity, she took up her pen and tried to ensure that no other woman should have to suffer the same tribulations. Her ardent pamphleteering on the ‘natural right’ of mothers to be with their young children helped to pass the Custody of Infants Act of 1839, which allowed women to petition for custody of children under seven and gave them access to their older offspring. It wasn’t until 1857, though, that an attempt was made via the Matrimonial Causes Act to provide better access to divorce, and even then it was heavily weighted in the husband’s favour. The Married Women’s Property Act took even longer: Caroline was 62 when it passed in 1870, finally giving her ownership of her literary works and earnings.

Caroline Norton is difficult to claim as a feminist hero. She did not question women’s overall subservience to men, arguing that the fairer sex needed ‘protection’, and some of her beliefs are incompatible with today’s understanding of women’s rights. She lived in a contradictory age: for much of her life, Britain had a female head of state, yet a Victorian woman had no separate legal identity.

There are both more scholarly biographies of Caroline and more titillating page-turners about the society affairs of this time. Those in search of extensive legal analysis or salacious scandal will not find it here. What Fraser does bring to the subject is her trademark blend of adroit character study and readable prose. She humanises the intricacies of Victorian legal precedent and makes it comprehensible to the lay reader.

She also avoids the trap of judging this 19th-century woman by today’s standards. Instead, she rightly draws attention to the way in which Caroline used her personal story to effect systemic change. Though widely criticised for deploying ‘woman’s tears’ and for caring only about improving her own situation, Caroline kept pushing for better legislation regardless. In this retelling, she is revealed in all her complexity: as a flawed, difficult woman who, against the odds, still managed to make the world better for the women who came after her.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in