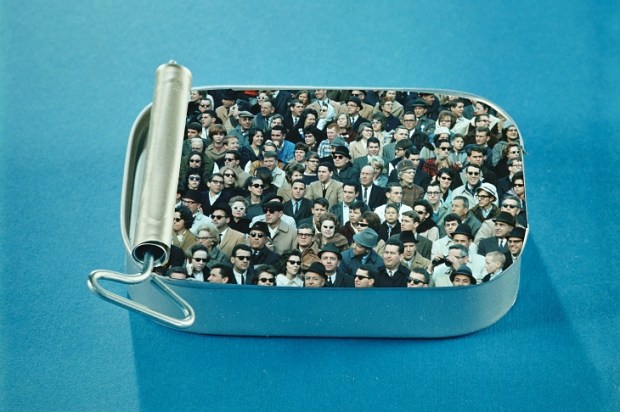

If there were a hint of a silver lining in the Covid-19 pandemic and associated travel restrictions, it may be this: Australian cities and communities have been given a much-needed breather from the frantic immigration-fed population growth imposed on us since the mid-2000s. But this respite will come to an abrupt end soon if Treasury gets its way.

Released last week, Treasury’s 2021 Intergenerational Report appears designed to serve as a propaganda instrument to reboot the ‘Big Australia’ mass immigration program. The IGR forecasts that net overseas migration will remain in reverse during 2021-22 as more people leave than enter the country. But NOM is then forecast to roar back to pre-pandemic levels to reach 235,000 people in 2024-25, and is assumed to stay at this high level for decades. Given Treasury’s role in setting immigration numbers, these forecasts should be viewed as a statement of intent.

Due to the pandemic-induced immigration interruption, Treasury laments that Australia’s population will grow slower than forecast in the previous IGR. Instead of exploding by a whopping 50 per cent to reach 38.8 million by 2054, it will now take an extra six years for the population to hit this mark. Oh, the horror. By 2060, immigration is expected to account for around 74 per cent of total population growth. Although it goes unstated by governments and politicians, Australia will be a very, very different place if this scenario comes to pass. To paraphrase L. P. Hartley, the future is a foreign country.

The IGR’s case for high immigration rests on the notion that, since Australia’s fertility rate is below replacement and the population is ageing, we need to stock the country with a lot more people. The reason we are said to need to import millions more people is to increase the working-age population relative to older Australians and shore up government finances. The insuperable flaw in this argument should be abundantly clear: migrants also age. And when they grow old and move into retirement, even more migrants will be needed to support them, and on it must continue, indefinitely — an obvious Ponzi scheme.

Perhaps the very clever Treasury bureaucrats really believe in population growth for infinity and beyond but, at some point, sanity and necessity will require the Australian population to stabilise (most other developed countries have already achieved this). Even if Australians are willing to stomach dramatic declines in living standards — which overpopulation would inexorably inflict — Australia would still eventually run out of resources to support a population expanding without limits. And once we hit the limit, we would still be left with an elderly population.

What’s more, far from solving our ageing population “problem”, there is evidence that elevated immigration levels have actually driven down the Australian fertility rate. Higher immigration tends to place greater upward pressure on housing costs and downward pressure on wages, thereby making it harder for younger Australians to establish themselves financially. This delays family formation and reduces family size.

Researcher Katharine Betts at the Australian Population Research Institute argues:

The projections show that if policy makers were serious about modifying Australia’s age structure the most cost-effective way to do this would be to support the two-child family. One way to do this would be to prune the immigration intake and, by reducing competition, improve housing affordability. This in itself would promote a modest increase in fertility from its current level of 1.74.

In any case, is an ageing population really such an utter catastrophe? Japan has the highest proportion of elderly citizens of any country in the world and is often cited by immigration boosters as a total horror show. But anybody who’s ever been to the country can see for themselves that it is far from a failed state or a decaying society. The country is rich, highly-advanced, and miles ahead of Australia when it comes to technology and generally delivering things that work well. Its citizens enjoy high living standards.

Compared to Australia, Japan has almost twice the proportion of older residents but nearly the same proportion of people participating in the workforce. With the same demand for workers and fewer working-age people competing for jobs, there is less unemployment and underemployment. And low-immigration Japan has also experienced stronger GDP per capita growth than high-immigration Australia over the last decade.

It is true that an ageing population will result in fewer people of prime working age per those in their retirement years and health care, aged care and pension costs will rise as a share of national spending. But this is offset by the reduced need for infrastructure and housing investment to cater for a growing population.

Conveniently, the IGR fails to account for the huge costs associated with adding an additional 13.1 million people to Australia’s population over the next four decades. Economist Leith van Onselen has pithily observed that “if the federal government was required to internalise the cost of immigration by paying the states $100,000 per permanent migrant that settles in their jurisdiction, so that the states can adequately fund the extra infrastructure and services required, then Treasury would no longer tout the ‘fiscal benefits’ of immigration.”

At some point, Australia’s borders will open again and immigration will resume. But it would be a big mistake to revert back to the extremely high immigration levels of the past decade and a half. Pre-Covid, polls indicated that a majority of Australians wanted lower immigration and slower population growth, with voters believing that high immigration was responsible for the deterioration of the quality of life in Australia’s cities. In addition to concerns over urban overcrowding and housing costs, Australians also had worries about the cultural and environmental impacts of high immigration.

In designing a post-pandemic immigration policy, the Morrison government should listen more to these voices — and less to unelected Canberra bureaucrats and those vested interests hooked on mass immigration as a source of cheaper labour and more customers.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in