Will no one rid us of our Covid-dementors? Gladys Berejiklian says restrictions could remain in place after 80 per cent full vaccination. Yet after weeks and weeks of ever-tightening restrictions, case numbers were still rising and last Friday crashed through the 800 daily ceiling. How does she think this will combat vaccine hesitancy?

Daniel Andrews has, if anything, become even more arrogant. The Doherty Institute’s Jodie McVernon and ANU’s Peter Collignon have seen no evidence that overnight curfews curb the virus spread. Andrews airily dismissed them: ‘It is not for me to prove the efficacy of any one measure’. Police Association Victoria Secretary Wayne Gatt wrote in The Herald Sun: ‘I hope that our members do not have to ever actively enforce this ban on playgrounds.’ He fears that enforcing ‘unpopular and deeply restrictive rules for a prolonged period’ would harm community support for the force.

In Canberra, suffering perhaps from relevance deprivation syndrome while macho state premiers imposed tough lockdowns to increased popularity, Andrew Barr declared a shutdown on 12 August based on one case. Yet a week later, with 67 active cases, there was not a single Covid hospitalisation in the ACT. Not to be outdone, across the ditch Jacinda Ardern shut down the whole country based on just one case.

Many of us have family (parents, siblings, children) in neighbouring and far-flung countries. Politicians and health bureaucrats cannot decide for us the balance of risks of dying from a virus and the joys of spending time with family in our remaining years. As a short-term holding operation while the world tried to figure out what was happening, the harsh restrictions were perhaps tolerable, if barely. Now, as data accumulates and the rest of the world opens up with significantly reduced deaths that contradict the embarrassment-proof Henny Pennies of the epidemiological community, the stubborn devotion to the cult of zero Covid is unforgivable. Remember news anchor Howard Beale in the 1975 film classic Network? ‘I’m a human being, Goddammit. My life has value … I’m as mad as Hell and I’m not going to take it anymore’.

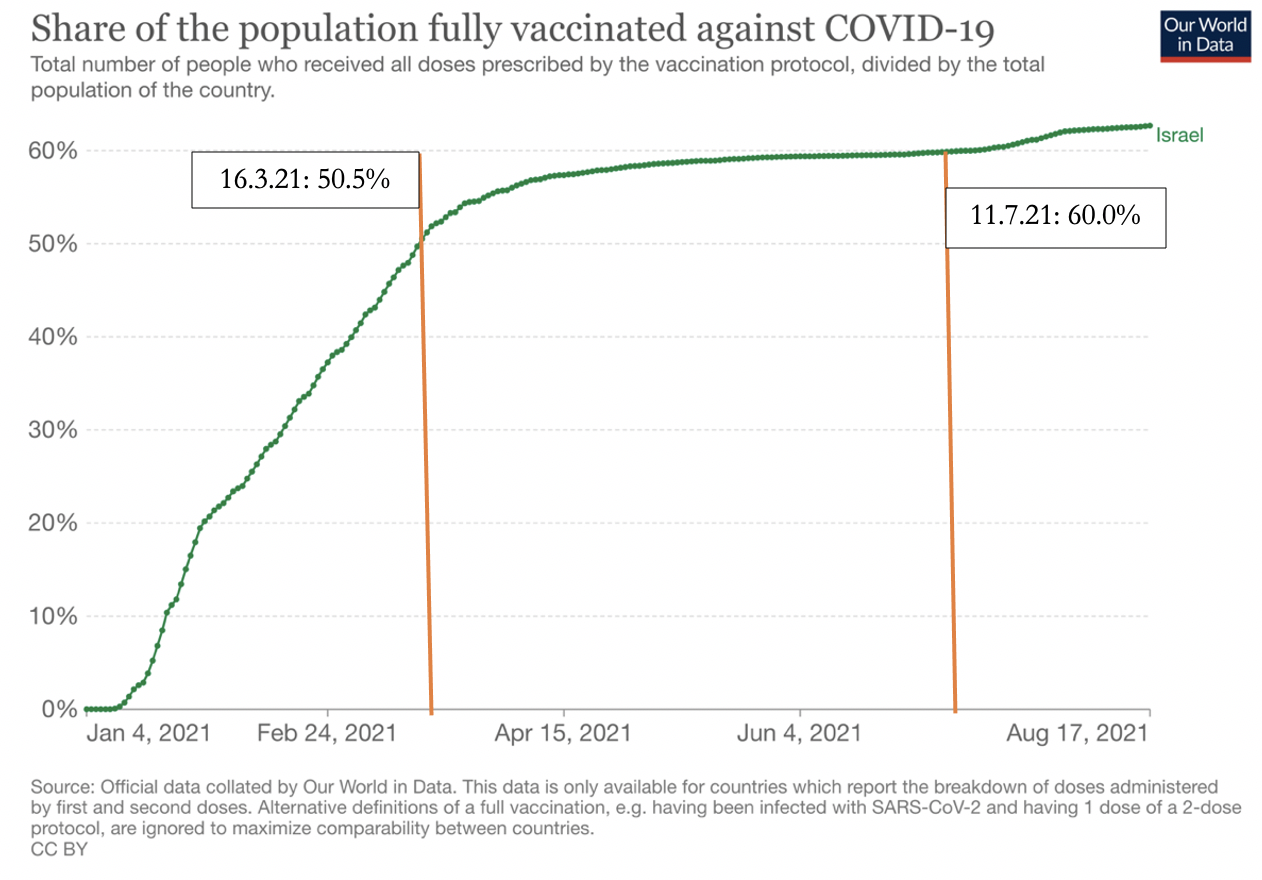

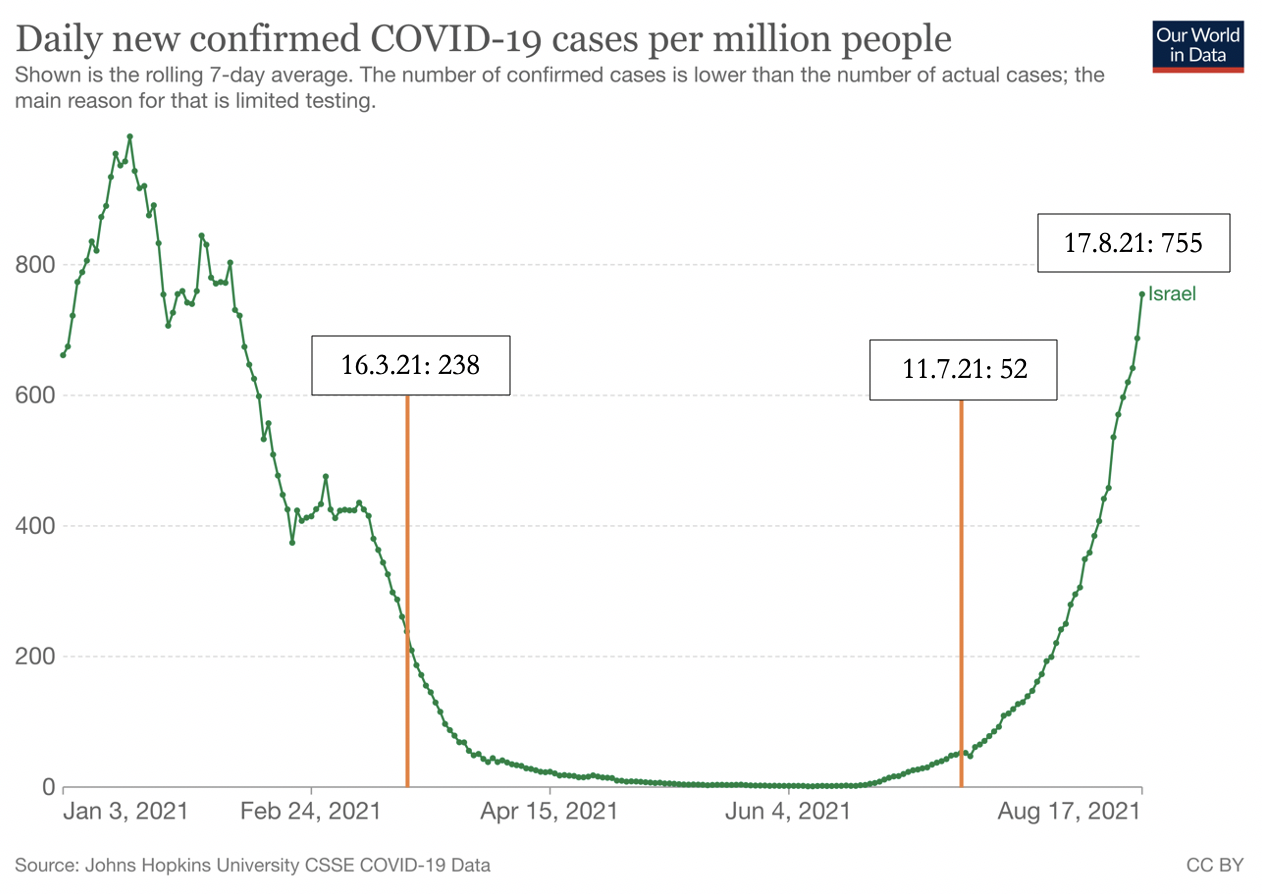

Iceland and Israel are two of the most heavily vaccinated countries in the world. Recently, 30 of a group of vaccinated Israelis who flew to Iceland contracted coronavirus. Half of Israel’s population was fully vaccinated on 16 March and, as of 17 August, 62.7 per cent of people – around 80 per cent of adults – were fully vaccinated (Figure 1). On 12 August, The Times of Israel reported, Israeli health officials warned that hospitals must prepare for an influx of nearly 5,000 coronavirus patients within weeks, half of whom will need acute care to deal with severe bouts of Covid-19. On the 18th, Coronavirus Commissioner Professor Salman Zarka said: ‘Morbidity is rising daily; I believe we are at war’. He foreshadowed the possibility of another round of tough lockdown during the High Holidays in September.

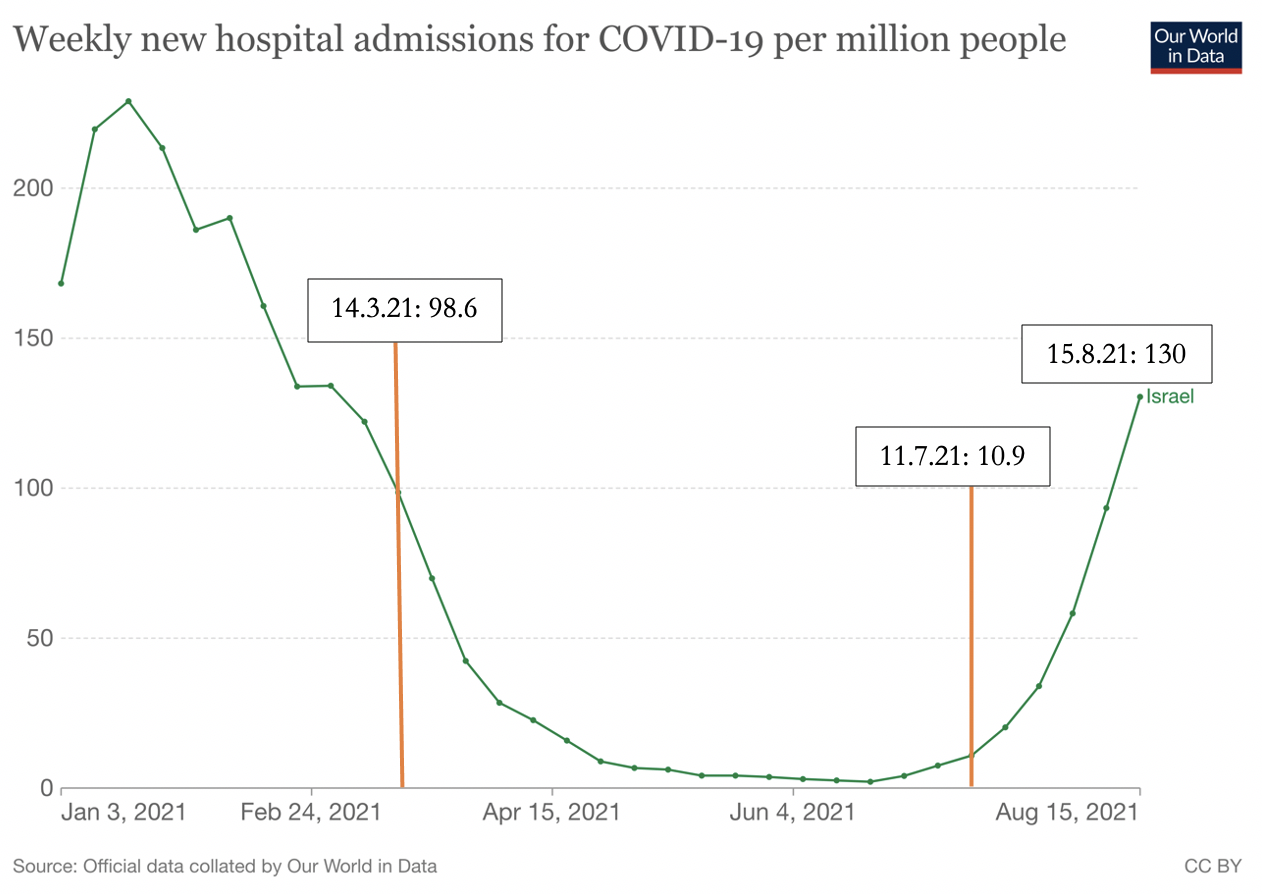

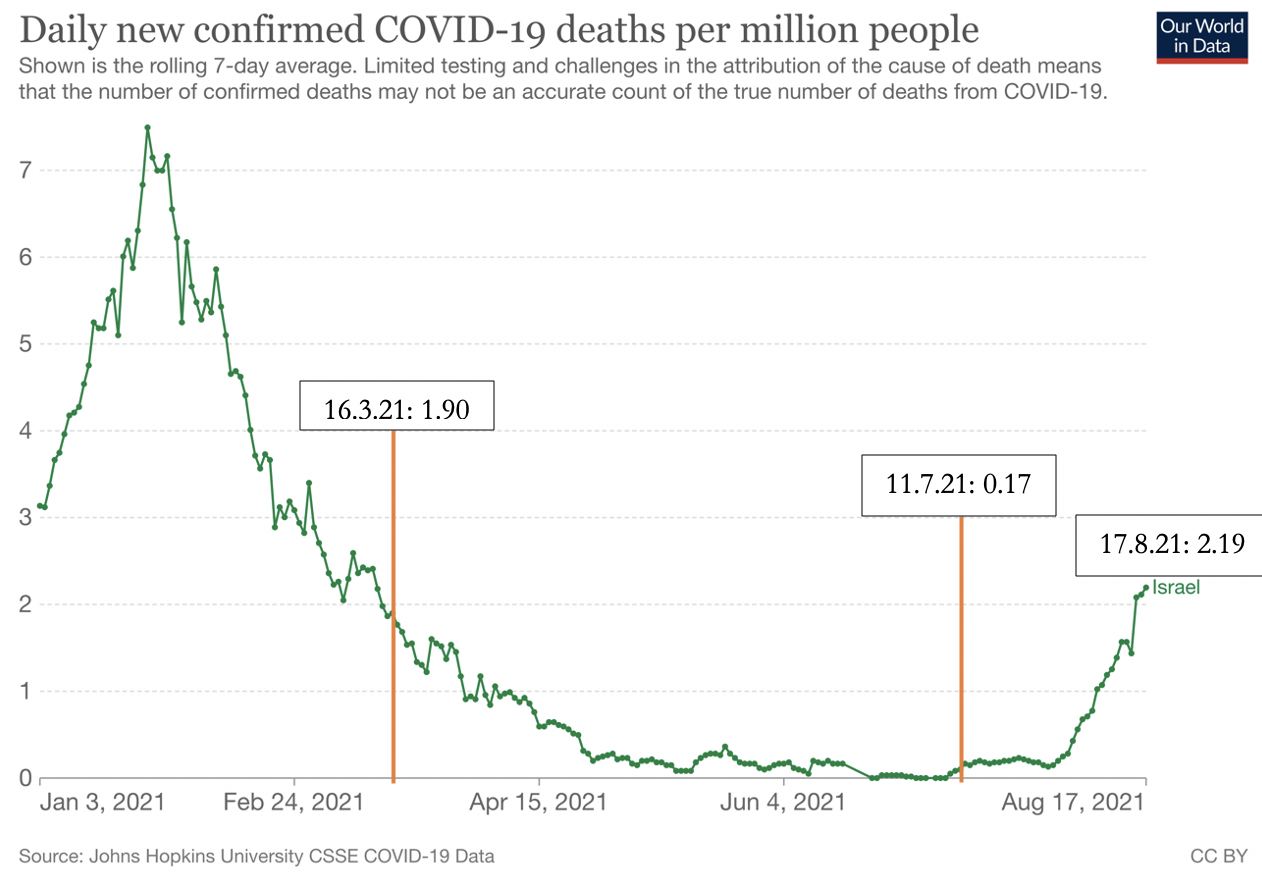

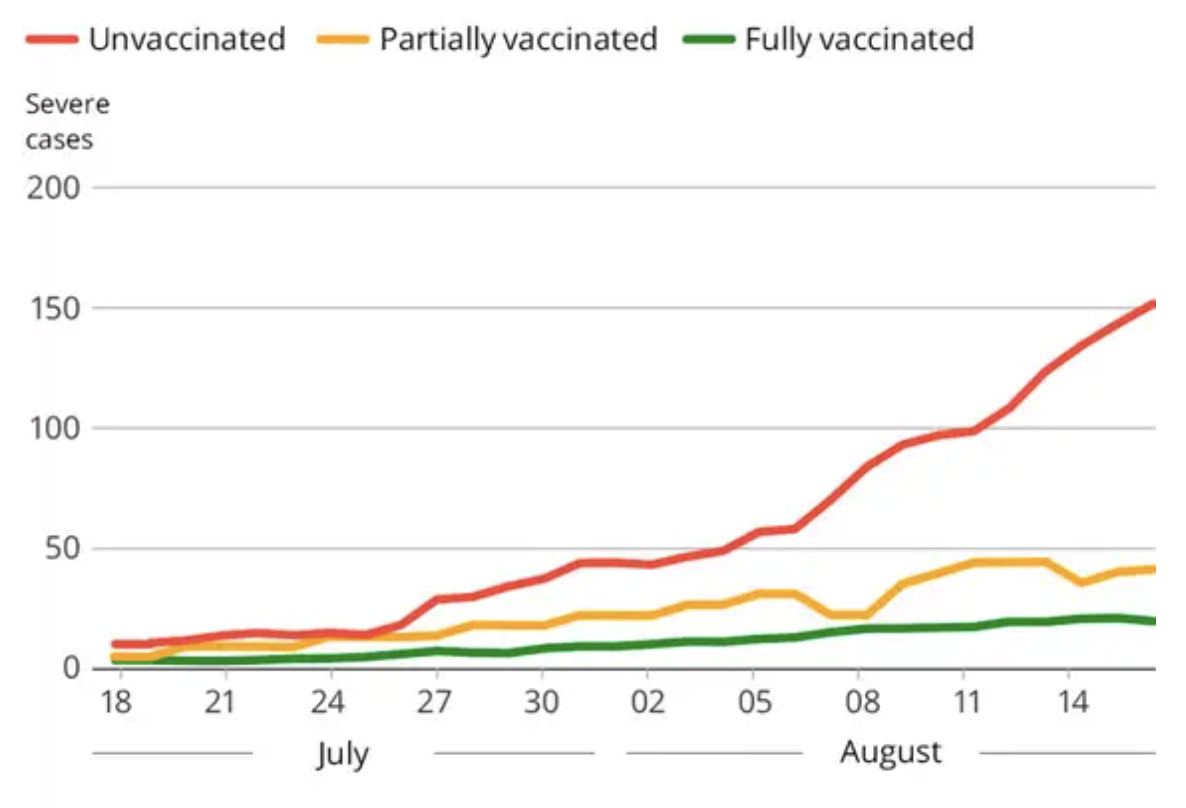

When Israel’s cases and hospitalisations peaked on 17 January (deaths peaked on 25 January), under 4 per cent had been fully vaccinated. Consequently, vaccinations cannot be solely credited for the second wave receding; other factors were also clearly at play. It’s equally true that even with over 60 per cent full vaccination, cases have exceeded the first wave peak and are nearing the second wave peak. But hospitalisations are 66 and 56 per cent of the first and second wave, respectively; and deaths are less than half the first wave and only about one quarter that of the second wave (Figures 2-4). From under 10 per cent on 31 May, Delta became the dominant variant of the virus a week later and currently accounts for 99 per cent of all cases. Thus the resurgence of the disease is largely explained by the far more aggressive Delta variant. The comparatively reduced hospitalisation and morbidity is likely explained by a combination of the high vaccine take-up and Delta being less deadly.

In earlier articles I referenced findings by Public Health England and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showing that vaccination reduces but doesn’t prevent infections. Moreover, fully- and un-vaccinated people have similar viral loads and so they spread Covid similarly. Both findings have been strengthened by a major new study from Oxford University based on data from 700,000 Britons, the largest yet to evaluate vaccine effectiveness against the Delta variant. Another important finding, relevant to Australian hesitancy over choice of vaccines, is that although Pfizer initially has greater effectiveness, this declines more quickly than AstraZeneca’s efficacy. The most important policy conclusion is that vaccines confer protection on the individual (Figure 5) but are not the pathway to herd immunity as they don’t significantly reduce transmission of the virus. There is no justification therefore for vaccine apartheid and these could be open to legal challenge.

Dr Michael Segal explains that vaccines injected into the muscles are very effective at stimulating internal immunity to protect the inside of the body, including lungs,, which helps protect the body of an infected person from being overwhelmed by the virus. By contrast, mucosal immunity protects the nose and mouth, and thereby reduces spread to others. Because jabs in the arm don’t bolster mucosal immunity, they don’t protect against infections in the mucous membranes and the infected people can spread the virus to others. Natural immunity from prior infection offers better protection than intramuscular vaccination against nasal infection and onwards spread. If this is true – only the medical scientists can answer that – the policy implication is that vaccines are better for personal protection but natural immunity is better for stopping the spread. A ‘downstream’ policy implication may then also follow: if the morbidity risks of Covid are highly age-segregated, is it better for society overall not to push vaccination in the low-risk young and healthy?

On 18 August, Israel’s 7-day moving average daily new cases was 6,110 – ten times as many as NSW; the daily new deaths were 20. Scaled up to Australia’s population, this would work out to nearly 17,000 new cases and 55 deaths daily. Australia’s actual total on 20 August for all of 2021 was 67 deaths. With these sorts of numbers of infected and dead on current policy settings, not one of the states or territories would open up even with 80% of the adult population fully vaccinated. That’s how tightly we’ve mousetrapped ourselves in pursuit of the illusory cheese of Zero Covid.

Figure 5: The graph that shows Pfizer vaccines work (Haaretz, 18 August 2021).

To escape the mousetrap, we should do the following:

- Set a hard target date for vaccines to be offered to all adults, with the date to shift if, but only if, the vaccine rollout hits a roadblock;

- Proclaim in advance the end of all restrictions throughout Australia on that date. Those fully vaccinated are better protected against infections and, if infected, against severity of illness. Those who have chosen not to be vaccinated are solely responsible for their decision and its consequences for their own health, but no more likely than the vaccinated to spread the virus;

- Announce that based on everything we now know about transmissibility and breakthrough infections, especially by new variants, domestic vaccination certificates are pointless and will not be required for any purpose. Similarly, there will be no compulsion as a condition of employment,, with the possible exception of aged care facilities;

- Terminate testing and contact tracing for asymptomatic people. It sustains a state of fear without serving any useful medical purpose;

- Issue clear and coherent guidelines on voluntary best practice personal hygiene and social interactions to reduce spread. This should include prompt testing with the onset of symptoms and isolation following clinical diagnosis;

- Loosen international travel but require rigorous protocols, including inexpensive and quick-results testing;

- Invest in high-quality assessments of the efficacy of newly developed and repurposed early treatment drugs;

- Invest in a substantial upgrade of the health, hospital and ICU infrastructure at the national level, with clear protocols for moving patients as required from infection hotspots to where there is spare capacity with guaranteed open state borders.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in