Here goes. The Young Vic’s Hamlet, directed by Greg Hersov, is a triumph. This is a pared-back, plain-speaking version done with captivating simplicity and perfect trust in the text. The star is Shakespeare and the production merely opens up an aperture to his dazzling account of human greatness and frailty. The action takes place on a small, level stage that could be covered by two bedspreads. Designer Anna Fleischle adds an oblong arch of distressed stone along with three tall blocks that rotate to create internal hiding places, corridors and cubby-holes. That’s all she needs to suggest a house of horrors, a court of nightmares, a royal palace beset by plots and whispers of secret killings. Every designer should see this Elsinore and learn how to generate a medieval kingdom from a handful of painted uprights. The audience’s imagination is the best material a designer has.

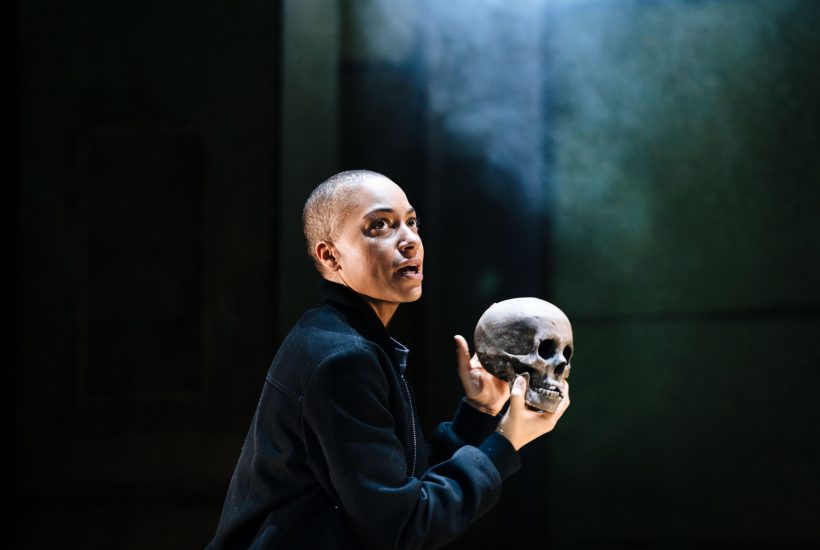

Cush Jumbo’s Hamlet is a shaven-headed, sexless rebel — a student anarchist on the loose. She slouches on stage in Act One (deliberately late for an official meeting) and surveys the court with a gaze full of mischief, anger and malevolence. This is a prince who knows all about depression and suicidal feelings, and who chooses to feign madness as an act of self-protection. But the pretence forces him/her to the point where actual lunacy becomes a danger. At moments of maximum stress, Jumbo twitches her hands and scratches at her temples as if trying to shoo an evil spirit from her skull. But these gestures emerge quite naturally from her performance, without any sense of deliberation or express purpose. It’s as if she hasn’t been directed at all in the role. She just is.

Her Horatio, Jonathan Livingstone, speaks the verse with great clarity and feeling, but he may have been miscast. He has the demeanour of a comedian. Tara Fitzgerald gives Gertrude an icily majestic presence and she benefits from a fabulous array of frocks and designer trouser suits. Joseph Marcell, exquisite and excruciating as Polonius, delivers a masterclass in prolix buffoonery. There’s even a hint of the Fonz about him — an ageing outcast who mingles with youngsters, and tries to muscle in on their pastimes, because the real grown-ups shun him. The casting of a female in the lead role creates difficulties in the final duel scene. Jumbo, who is slender and narrow-shouldered, cannot possibly match the athleticism of Jonathan Ajayi’s pumped-up Laertes. And yet Hamlet must beat him in a deadly sword fight. The answer is to arm the pugilists with short knives, instead of sabres, which neutralise Laertes’s physical superiority and make Hamlet’s victory seem credible.

There are a few minor gripes. Could the death of Gonzago reach its conclusion with more impact? Certainly. (The thunderous line, ‘the king rises’, wasn’t heard on press night.) Might Adrian Dunbar (Claudius) lift his head an inch or two and project his voice at the crowd rather than at his chest hair? Yes, please. Does Ajayi’s Laertes rely too much on the gangsta gestures and cadences of south London? Unfortunately so.

Might the set itself be overly sparse, too devoid of large furnishings? Indeed, yes, but there is method here. Furniture is costly to lug across the Atlantic and the producers seem to have countenanced just such a journey. Good. Their ambitions deserve to be fulfilled.

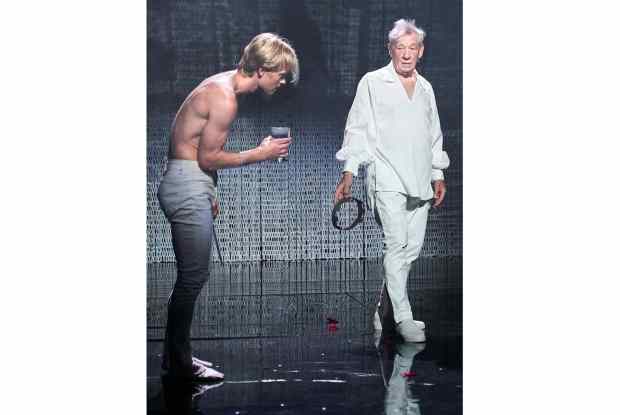

Caryl Churchill returns to the Royal Court with a new play. Or sketch, really. It lasts just 18 minutes. A sorrowing widower, drinking alone at night, begs to be reunited with his dead wife. A female ghost appears. This, however, is not his wife but a metaphysical apparition who stands for the future. Or perhaps she stands for several possible futures. She keeps changing her mind about who she is or what she signifies. The widower collapses and screams at her in anguish. But she keeps rabbiting on at him until the walls of his bedroom start to rise from the ground and a new character appears. A small boy. He represents the present.

Churchill’s effort feels like a stab at a Monty Python routine. And it’s not the first time she has drawn inspiration from their intellectual surrealism. Her 1982 play Top Girls includes a handful of historical figures who indulge in absurd Pythonesque monologues. In this new sketch, John Cleese would be ideal casting as the anguished widower. And Michael Palin could play the annoyingly helpful ghost brilliantly. And the result would be really funny rather than just moderately engaging.

Some may ask why Churchill’s latest work has been produced at all. Samuel Beckett used the word ‘dramaticules’ to describe his minor scribbles, as if their brevity were intentional. Don’t believe it. Dramatists regularly abandon scripts because they lose interest and move on to a more inspiring idea. But few writers are lucky enough to see their discarded jottings put on stage. Be in no hurry to inspect Churchill’s leftovers.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in