The story of the Cambridge spies has been served up so often that it has become stale — too detailed, too predictable, too firmly etched in Cold War monochrome. So it’s a good idea to seek another angle, through the warmer lens of a love affair involving its main protagonist Kim Philby and his wife Eleanor. It humanises the tale, particularly as it draws on a vivid and neglected personal source — The Spy I Loved— Eleanor’s own book centred on their romance in the Lebanese capital, Beirut.

That was where Philby was despatched in 1956 to play out the penultimate act in a drama stretching back to the 1930s, when he and his fellow Cambridge students were recruited to spy for the Soviet Union. Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess were rumbled, and fled to Moscow in 1951. Philby beat the rap for a bit longer, but was damaged goods. So, needing him out of the way, his MI6 employers arranged him cover as a correspondent for the Observer and the Economist in Beirut, which, like Bucharest in the 1930s and Lisbon during the second world war, was enjoying a post-Suez moment as a hotbed of international espionage.

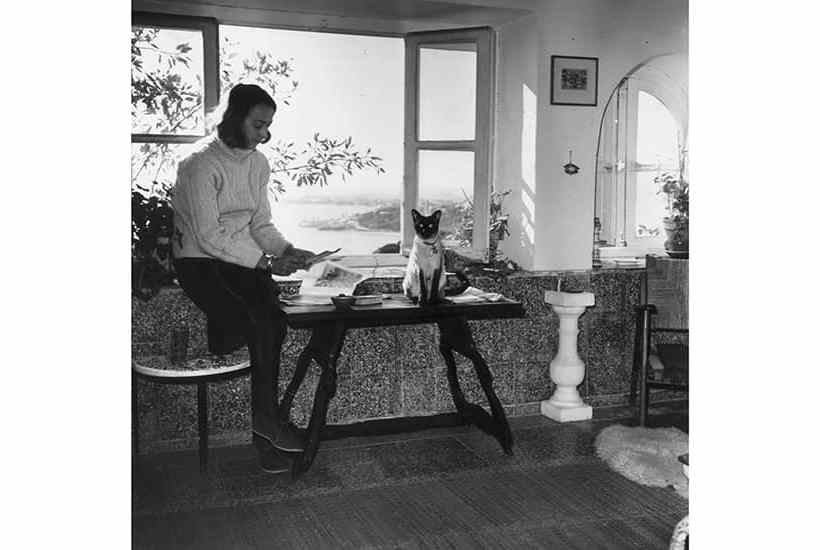

With nothing much to occupy him (he still performed minor tasks for MI6, between journalistic sorties involving, as someone noted, little Observing or Economising), he fell in love with Eleanor Brewer, the bright but frustrated wife of the often absent New York Times bureau chief. It didn’t take the libidinous Philby long to ditch his own spouse Aileen, an embarrassing alcoholic, and hitch up with Eleanor.

James Hanning has a fine feel for the mutually advantageous relationship between newspapermen and spies. With the often sozzled Philbys at the centre, he wheels us through Beirut’s bars and hotels, notably the Normandy and St Georges. We meet flamboyant figures such as Miles Copeland, the former (it appears) CIA man who still relied on Langley for his vast expense account. He, Kim and their families became firm friends. Proof that expatriate women didn’t just stay at home and ‘bake brownies’, Copeland’s wife Lorraine, a gifted Scotswoman who worked for SOE, took Eleanor on archaeological digs. The Copelands’ son, Stewart, drummer with the Police, remembers Eleanor as ‘hot’, although Hanning’s predilection for the recollections of participants’ offspring generally adds little.

On the positive side, he casts his net wide. We learn of hitherto obscure characters such as Myrtle Winter, an indomitable and witty MI6 veteran who had travelled the world, and the deliciously camp British ambassador, Sir Moore Crosthwaite, who put the embassy’s vast Austin Princess at Eleanor’s and Lorraine’s disposal for jaunts in the hills.

Inevitably the back story of the Cambridge spies needs addressing, not least because the book’s second half deals with the finale — Philby’s own disappearance to Moscow, and its aftermath. This followed MI6 obtaining cast-iron evidence of his treachery and sending his friend and one-time colleague Nicholas Elliott to Beirut to obtain his confession. But the old Etonian Elliott was the wrong person for this job. He left Philby with the time and motivation to flee the Lebanese capital on board a Russian freighter in January 1963.

This raises the old conundrum — cock-up or conspiracy? Perhaps the Brits wanted him in Russia where he would be no embarrassment. Or was he tipped off? Hanning believes so, and has his own well-argued take — that Philby was warned that MI6 was now convinced of his treachery by an old accomplice, Anthony Blunt. According to Hanning, Blunt flew to Beirut not once (as is generally known) but twice before Philby’s disappearance. Blunt claimed to be interested in finding a ‘rare Frog orchid’, which Hanning suggests was some sort of gay code (intended for Crosthwaite). More to the point, Blunt had his own reasons, as he was afraid Philby would expose him as a Soviet spy.

As this book is also about Eleanor, her reactions add to the excitement. Of course she was devastated. But Philby sent money and begged her to join him in Moscow. She was delayed by all sorts of impediments, including her ex-husband suing to prevent her seeing their daughter Annie. At one stage she hoped to reach Moscow by secretly changing planes in Prague. This plan was rumbled, most likely by Myrtle Winter, though Hanning puts another person in the frame — Patrick Seale, Philby’s former Observer colleague and Eleanor’s ghost-writer. Hanning raises an old canard that Seale worked for MI6, an idea he plays with but fails to make stick.

All this is conveyed clearly and entertainingly. Indeed its oblique perspective makes Love and Deception as good an introduction to the whole murky Philby business as any. Personal liaisons are sensitively explored, locations brought to life, and it’s all neatly cross-referenced with local and world affairs.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in