Two members of parliament have been killed in the past five and a half years. This, one long-serving MP laments, is the kind of statistic you would expect in a failing state.

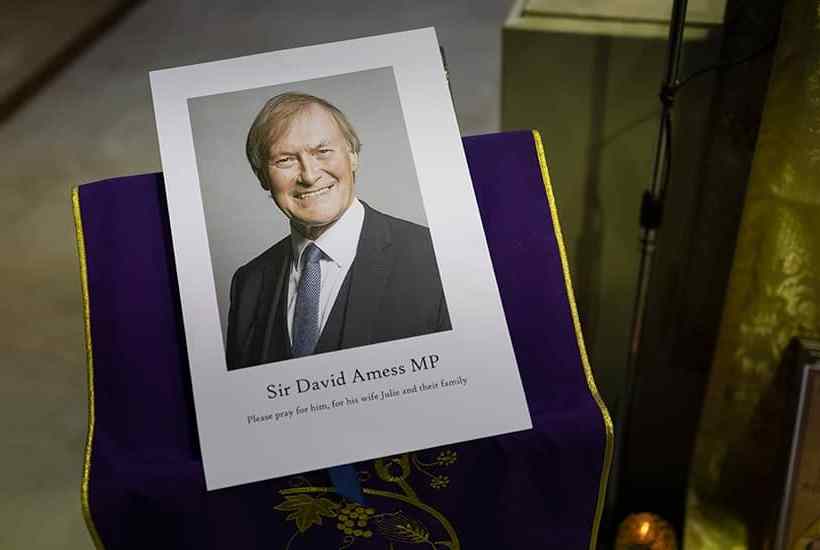

One of the shocking things about Sir David Amess’s murder is that many MPs weren’t surprised by it. Parliamentarians are acutely aware that when they are away from the Palace of Westminster, with its armed guards and security scanners, they are a soft target. Their job requires them to mix with the public and that involves a certain level of risk. One senior Tory MP points to how during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, MPs who were thought to be in particular danger were offered a firearm for personal protection, and argues that an offer like this should be extended to all MPs today. Few would go this far, but the comment reveals how much concern there is about the situation.

Whenever a killing is investigated as an act of terror there is always a tendency to declare that any change to how things are done would be a victory for terrorism. While a few MPs have called for changes to how constituency surgeries are held, many more want them to carry on as they were.

Given the circumstances, the rethink of safety procedures for MPs should be a practical exercise, not a philosophical one. When in response to the IRA bombing campaign Margaret Thatcher put a gate across Downing Street, without which an IRA mortar would have killed the war cabinet in 1991, it was not a ‘victory’ for the terrorists but a prudent security measure. The same applies to the protective cars for US presidents: open-top vehicles were ditched after Kennedy’s assassination.

Jo Cox and David Amess were killed either at a surgery or on the way to one. Stephen Timms, the Labour MP for East Ham, survived a stabbing at his constituency surgery in 2010. Privately, several police forces have advised MPs to move away from openly advertised events. In the modern era, when MPs are more contactable than ever before, such a move shouldn’t cut politicians off from the public. Constituents would still be able to see their MPs, but meetings would have to be arranged in advance. This change would be in all of our interests. If the current sense of danger persists, more and more good people will decide that they cannot subject their families to the risk that political service now incurs.

Another change many MPs would like to see is an end to internet anonymity. The Tory MP Mark Francois argued in the Commons that this would be a fitting tribute to Amess, a ‘David’s law’ which would help restore some civility to politics. Francois suggested that the government’s forthcoming ‘online harms’ legislation provides an obvious vehicle for this.

At the moment, many MPs — even some who are normally quite libertarian — are sympathetic to ‘David’s law’. This is quite an understandable reaction, given the abuse they receive from anonymous accounts on social media, but there are risks to the end of anonymity. Many MPs argue that a person should be able to use social media accounts under a pseudonym but the platform should have a record of who that person is. The problem with this approach is that any database of who is linked to what account could be hacked. The rocketing levels of online banking fraud are a reminder of how difficult it is to achieve failsafe online security.

Then there is the question of whistle-blowers. Genuine anonymity makes it far easier for people to alert others to malpractice in their own organisation. There is an international consideration too: if Britain were to ban online anonymity, the precedent would be seized on by repressive regimes around the world to justify their actions.

Online anonymity might mean people are more abusive than they would be if they had to use their own name, but the costs of ending anonymity are so high that MPs should not consider it. But there does need to be a cultural change. Online threats of violence need to be taken more seriously by both the police and technology companies.

The biggest online issue is how the internet speeds up the process of radicalisation, taking people further and faster down the path of extremism than they might otherwise have gone. One former minister who has examined the question of online regulation argues that ‘the root cause of the problem is the algorithm’. Social media companies use algorithms which attempt to serve people more content that they might like. In most cases, this process is harmless. But in some cases, it can lead people to dark places.

The security services have warned that lockdown means that they worry that more people will have been radicalised online in the past year. They are particularly concerned about how many young men might have been lured into Islamist extremism. Those who are radicalised on the internet are harder for security services to track, since they don’t leave behind a physical trail.

This is a hard problem to solve. Tech firms don’t want to publish their algorithm because that is their most valuable piece of intellectual property. But it is evident many of them are contributing to the current unhealthy culture of political polarisation and, at worst, they might be hurrying some damaged individuals towards violent extremism.

There needs to be far more transparency about how these algorithms work. There is also a strong case for, as the Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen has argued, appointing external figures to supervise social media companies from the inside.

The polarisation of our political culture and the threat of terrorism are not the same problem. Yet the solution to both problems relies on working out how to effectively regulate social media without descending into authoritarianism — something that no liberal democracy has yet found a way to do.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in