If truth were a commodity, you’d short sell it. Think the Coates enquiry into hotel quarantine, cheap renewables and so on ad nauseam. So, what price the Victorian truth-telling extravaganza – the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission?

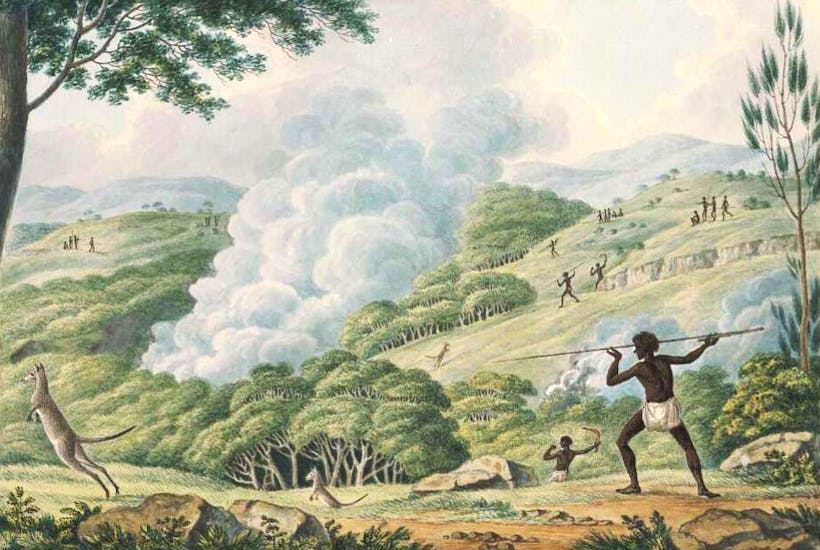

Recently The Guardian on the Yarra (aka The Age) ran a series of articles on this latest talkfest under the headline ‘Time for Truth’. This included articles by Tony Wright extolling the way the Aborigines managed the Victorian landscape for 40,000 years, the tragic story of Kalloongoo, sold as a ‘slave’ to settler William Dutton, and recounting the various massacres and other depredations inflicted on the indigenous inhabitants. It contains a number of other pieces by different Indigenous people recounting their own history.

The Commission is an official inquiry into the impact of colonisation on First Nations peoples in Victoria. It is the first of its kind in Australia. Its purpose is to bring about change for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Victoria through a process of truth-telling and healing. The commission will hear their experiences, helping the broader community understand past wrongs, injustices still happening, how the injustices occurred and who or what is responsible.

There is no doubt that Aboriginal history since colonization is littered with despicable events and tragic outcomes for many indigenous people. The worst of white depredation has already been given great prominence thanks to various historians and activists. Of these, the most unarguably wrong is the initial dispossession. However, that is now a fait accompli and, whatever view you have of it, any attempt to turn it back – which is what this process is all about – is destined to further divide us. Most, if not all, of the loudest voices pushing these agendas owe their comfortable lifestyles, indeed their very existence to colonization.

Colonization was traumatic. There can be no doubt about it. But most of the trauma was visited upon those now long dead. The shape of modern Aboriginal society dates back to 1967, when Australians, at the behest of Indigenour people themselves, voted overwhelmingly to allow the Commonwealth to make laws for the benefit of Aboriginal people. Since that time, Indigenous people have flourished in all walks of life.

In 1968 Lionel Rose became the ninth Australian of the Year and the first of nine Aboriginal recipients of that honour. In 1993, the High Court, discovered the concept of Native Title, as a result of which Aboriginal organizations now have title over more than 30% of the Australian landmass and are on course to achieve 60%. In 1995 the Aboriginal flag was adopted as one of our official flags and now flies outside every public building in the land. In 2008, the Prime Minister of Australia issued an official apology for the so-called ‘stolen generations. That, along with other events, is now enshrined in our calendar.

Not a day goes by that Aboriginal achievement, both past and present, is not celebrated across the country. Every day, somewhere, at least once, an ‘acknowledgement of the traditional owners and elders’ is conducted, or a ‘welcome to country’ ceremony performed. The opening ceremonies of sporting events, such as the Commonwealth Games at the Gold Coast, are replete with Aboriginal themes and participation. Aboriginal sportsmen and entertainers are feted and paid the same as their ‘white’ confreres. Aboriginal academics have access to special resources and programs. Educational curricula across the country have mandated indigenous cross-cultural content in all subjects. I could go on, but you get the picture.

And yet, it seems, we need another commission, at great cost to the long-suffering taxpayers of Victoria, to ‘heal the wounds of the past’.

The Age articles contain a mix of past ‘atrocities’ and personal accounts of racism experienced by people currently alive.

I don’t intend to truth-check all the accounts of historical atrocities, but I can attest that at least two of those cited by Tony Wright are, at the very least, contestable.

The first of these is the so-called Convincing Ground massacre in which a whole tribe was supposedly massacred. In fact, what occurred was a spat between some whalers and a small group of Aborigines over the harpooned carcass of a whale on the south coast of Victoria near what is now Portland. A few Aborigines were killed, principally because their weapons were no match for the whalers whom they attacked. The Henty brothers recounted this incident to Aboriginal Protector George Augustus Robinson a few years after the event. Robinson turned it into the massacre of a whole tribe. Thanks to historian Michael Connor, you can read a detailed account of this incident and the myth it spawned.

Wright also refers to Gippsland pioneer Angus McMillan, now known as the Butcher of Gippsland, disowned by his descendants and stripped of the honour of having a Federal seat named after him. He is accused of forming and leading a vigilante group known as the Highland Brigade in what is now termed the Gippsland Massacres.

These massacres achieved popular recognition through Don Watson’s book Caledonia Australis: Scottish Highlanders on the Frontier of Australia, published in 1984, and Julian Drape’s Our Black History: The Kurnai of Gippsland, published in 1998. Drape claimed that Gippsland’s once-revered pioneer Angus McMillan led others who ‘ambushed as many camps as they could find, killing every man, woman and child’ and that, over 15 years, these depredations reduced the Kurnai population from 2000 to 126. This story also appeared under the heading ‘Massacre of the Kurnai’ on the Ergo website of the State Library of Victoria. McMillan has now been so thoroughly demonised that some of his descendants have disowned him and the federal electorate of McMillan, originally named after him, has now been renamed Monash. His Wikipedia entry also claims that he led many massacres.

But is it true? Historian Andrew Dawson has uncovered an interesting chain of evidence that indicates that most, if not all, of what we are now told about McMillan, the mass murderer, is based purely on conjecture. All the sources for this alleged massacre have their genesis in a 1983 book by Peter Gardner, The Gippsland Massacres: The Destruction of the Kurnai Tribe 1800–1860. The direct evidence for massacres on the scale proposed by Gardner is contradictory, fragmentary and anecdotal. Dawson has shown, in a paper presented to the State Library of Victoria, that the most convincing evidence for the massacres, an eye-witness account by a pastoralist named Parsons, to a Caroline Dawson in the 1860s, is a fabrication. Both Parsons and Caroline Dawson are fictional characters. The State Library of Victoria found Dawson’s case convincing enough that it removed its ‘Massacre of the Kurnai’ article from the Ergo website. It has now contented itself by merely noting, in a different article about Angus McMillan, that he was ‘involved’ in Aboriginal massacres.

It seems undeniable that McMillan was involved in the deaths of some Aborigines killed in reprisal for either killing or stealing stock and/or killing settlers. In this, he was no more nor less culpable than most of his contemporaries. However, thanks to Peter Gardner and others, Angus McMillan has been thoroughly demonized.

But the contention, put by Gardner and a number of other commentators, that he was instrumental in establishing a vigilante force known as the Highland Brigade whose raison d’etre was to wipe out Gipps-land Aborigines is not based on any credible evidence. In fact, the term Highland Brigade, which appears regularly in modern accounts of the ‘Gippsland massacres’, does not appear in any original source that I could find. It gets most prominence in the form of Thicker than Water, a virtue-signalling book by McMillan’s great-great-niece, Cal Flyn.

But if I have still not convinced you that the provenance of Gardner’s work is questionable to say the least, let me conclude with the Tambo Crossing massacre detailed in the University of Newcastle Massacre website.

The website entry states that between November 1843 and June 1844, settlers massacred 70 Aborigines at Tambo Crossing in eastern Victoria. The original source for this is attributed to Aboriginal Protector George Augustus Robinson who travelled through that area in 1844. The website states:

This incident was originally reported by G.A. Robinson Report of a Journey of Two Thousand Two Hundred Miles to the Tribes of the Coast and Eastern Interior during the Year 1844, (Mackaness 1941: 13). Gippsland historian Peter Gardner re-read the report in 1996 and considered that the high number of Aboriginal deaths ‘upwards of seventy’, was not customary in Aboriginal society and that Robinson’s statement: ‘best forget the whole sale slaughter by Christians’, was a clue to the organisation of the slaughter by white people. Carried out by white men assisted by Omeo and Mokellumbeets and Tinnermitum warriors (Gardner 1996:49-51).

In fact, Robinson briefly referred to the event in the report of his trip in 1844:

A deadly animosity exists between them and the natives of the coast; a whole tribe having been destroyed by the Yattemittongs and their allies a short time previous. Blanched human bones strewed the surface and marked the spot where the slaughter happened.

But Gardner takes the view that the enmity between these tribes had existed for generations without them wiping each other out and that it is only white agency that could achieve slaughter on the scale claimed and also, apparently, the degree of organisation required – which seems a rather racist assumption. The only problem with this scenario is that, at the time, there were only five stations, widely separated, in the Omeo district. It is hard to imagine that these settlers would have had the will, the capacity or the motivation to recruit native allies and mount an operation against one particular tribe on the basis of what the University of Newcastle website entry describes as ‘opportunity’.

So, to summarise, Robinson reported a massacre of one Aboriginal tribe by a group of others. That event was described to him, with ‘zest’, by an Aborigine (Charley) who claimed to have been there. Robinson did not say that Charley reported the presence of Europeans. Robinson was a Protector of Aborigines and deplored the mistreatment and killing of blacks.

And yet, based on one cryptic comment, Gardner has exonerated the blacks (other than as possible accomplices) and created a white massacre.

I am not claiming that massacres did not occur, but if three massacres can be contrived out of the written record, one wonders what ‘history’ could not be conjured out of the oral tradition of Aboriginal activists invited to tell their story to the Commission.

As to the story of Kalloongoo, no doubt her life was tragic, certainly by today’s standards, and we can deplore what happened to her. But her story is no more relevant to the plight of individual Aboriginal Australians today than are the stories of the 162,000 convicts transported to Australia, to their descendants today. Life back then was brutal and it wasn’t just the colonizers who perpetrated atrocities. It’s quite possible Kalloongoo was not kidnapped by sealers, as recounted by Tony Wright, but bartered by her tribe. Both Charles Sturt and Thomas Mitchell recount being offered women in gratitude for the gift of a tomahawk. As unwoke as it is to say it, life for Aboriginal people prior to colonization was certainly brutish if not entirely nasty. Here’s some more truth, although I doubt you will see it emerge from the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission. Infanticide and cannibalism, often linked, was commonplace. But don’t take my word for it. Bill Rubenstein provides chapter and verse.

As to the efficacy of commissions getting to the truth, how did that go in the case of say, the ‘stolen generations’? Conservative commentators, notably Keith Windschuttle, Andrew Bolt and Tony Thomas – to name but a few – have been calling out this myth for years. And more importantly, backing up their claims with forensic research. Bolt has issued a challenge for anyone to name just 10 Aborigines taken into care simply because they were Aboriginal. He is still waiting for a response. You can read the latest instalment in this rear-guard action by Tony Thomas here. Tony reveals the anger of Nicholas Hasluck, the son of former 1950’s Minister for the Territories, Sir Paul Hasluck, at having his father effectively accused of genocide by the Wilson report. And yet this myth has achieved CAGW status of unchallengeability. That’s what you get from commissions – particularly in Victoria.

The activists, of course, tell us that racism is by no means confined to the past, and in those Age articles you get many examples of modern-day racism. For example, Gunditjmara man, singer, author and poet Richard Frankland, tells us:

As a peacetime soldier in the ’80s, I witnessed fellow diggers go ‘boong bashing’, saw hundreds if not thousands of my mob living in ‘humpies’ from the far north and the far west to the islands and to the south, those people being excluded from broader society.

As to diggers going ‘boong bashing’, I served in the Army during the 80s and this claim, in the absence of any details, seems doubtful to me. These sorts of claim are easy to make and have no provenance. And hundreds if not thousands of Aborigines live in humpies largely because they choose to do so, and none are excluded from broader society.

Racism certainly exists in Australian society, as does paedophilia, murder, incest, rape, and a myriad of other anti-social activities that are regarded as an aberration. Where examples of racist attacks occur against an individual, and to the extent they are real and not imagined (an increasingly common phenomenon), they may be regarded as hurtful, but no more significant societally, than any of those other offences. A little perspective wouldn’t go astray.

To paraphrase Mark Twain, there is truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. You might get a bit of the first from the Yoo-rrook Commission, but don’t expect any of the other two.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in