In the 1964 film My Fair Lady after Colonel Pickering has secured the help of an old friend to pull strings at the Home Office (plus ça change) in the hope of finding the absconded Eliza Doolittle, Professor Higgins snaps:

Why is thinking something women never do?

And why is logic never even tried?

Straightening up their hair is all they ever do.

Why don’t they straighten up the mess that’s inside?

Today the sex and gender wars are more nuanced than that, at least in public, but the charge of stupidity and unthinkingness has found many other targets: anti-vaxxers, Brexiteers, conspiracy theorists, climate- change activists on the M25, Republicans, Democrats and the Prime Minister (if only he’d straighten up his hair).

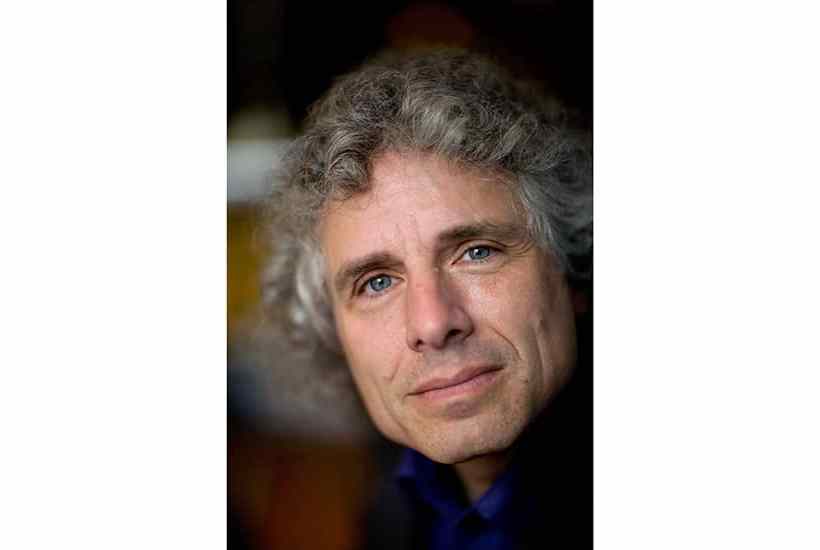

Unlike Henry Higgins’s pointed criticism, Steven Pinker, a Harvard professor of cognitive psychology and seasoned populariser of subjects far beyond, sees a mess inside every one of us. He takes an evolutionary perspective to argue that the mess is getting worse; humans aren’t used to the volume, immediacy and pace of information that fuels our connected lives. In essence, we fail woefully to be rational. But do we really want to fare better? Rational personalities can seem dull and inhibited. And there’s entertainment to be had in spurning the fact-checkers and half believing the outrageous stories that reach our Twitter feeds.

What is rationality? Pinker settles on the definition that it’s ‘the ability to use knowledge to attain goals’, or to work with the truth to get where we want. The opposite of rationality is harder to define. It’s not strictly unreasonableness, or illogic, or emotionality, as all of these can be rational (Pinker does a good job in explaining how). Rationality cannot tell us what to value, at least not directly. But assuming our values are well-intentioned, people can be ‘goaded into applying their best habits of thinking’ to avoid the ‘siren songs that lure us from good decisions’. Rationality is a muscle of sorts, or rather a collaborative group of muscles. Pinker has the noble aim of making cognitive exercise as aspirational and appealing as working on your six-pack.

There’s a skill in identifying tempting wrong answers to a question that lead you to the right one. Imagine buying a smartphone and a case, costing $110 in total. ‘The phone costs $100 more than the case. How much does the case cost?’ You know that if the answer were $10, Pinker wouldn’t be asking the question. It’s easier to resist the round numbers ($10) when the scenario is packaged as a test, and you want the dopamine hit of getting it right ($5). But when these scenarios are woven through our daily lives — in sales pitches, investment opportunities, the six o’clock news — with less predictable rewards, our brains are rash and vulnerable.

Pinker is indebted to the psychologist Daniel Kahneman, who wrote the 2011 smash-hit Thinking, Fast and Slow, that describes how humans are crippled by cognitive biases. We tend to think linearly rather than exponentially, underestimating the value of saving money over the long haul or the rapid spread of a virus. If we have examples to hand, we overestimate both risks and benefits. After hearing about a drowning accident, we’re more likely to fret about our next wild swim.

It’s very hard to put probabilities into words. Even Pinker’s use of ‘scarce’ in the book’s title hints at this difficulty (is that less common than rare?). Data, while much more precise, and therefore essential to public communication, can also be highly misleading. Pinker’s discussion of Bayesian reasoning, like much of the book, is fascinating. His example emphasises why rationing medical tests is often a public good, particularly for hypochondriacs. Investigations on request can spiral rather than quell our anxieties. Imagine the prevalence of breast cancer among women is 1 per cent (it isn’t), and all women are to be screened. When the test result says ‘cancer’, it’s correct 90 per cent of the time, while the rate of false positives — the test says ‘cancer’ when it’s not — is 9 per cent. If a patient’s test comes back positive, how likely is it that she has the disease? A group of doctors, trained in interpreting and communicating risk, said 80 to 90 per cent. But it’s just 9 per cent.

The key is to look at the base rate of the disease. In this scenario, not having cancer is 99 times more likely than having cancer. If you neglect your ‘priors’ — Silicon Valley slang for your sense of how likely something is based on what you know before you look at a lab result or read new information — you can easily be led astray. Faulty memories, faulty perceptions and faulty tests are more common than tragedies and miracles.

Rationality doesn’t only outline our flaws, but also suggests ways to minimise them. Deriving and storing knowledge in communities — colleges, think-tanks, the media — prevents the biases of individuals running riot. The randomised controlled trial, for example, is ‘an impeccable way to cut these knots’ of irrationality, Pinker argues, because the randomising, double-blind design and the intervention vs control arms of the experiment minimise human meddling.

Still, these collective efforts need to win our confidence. I’m a doctor, but my understanding of how the Covid vaccines work is superficial. I took my vaccine not because I reasoned my way there from first principles: I trusted, and was led. Pinker advises we choose our company well, as it feels better and safer to make decisions that align with those around us. For me that’s a tribe of compassionate nerds, not people who watch Fox News. Vaccine uptake is higher in the UK than the US not because we’re more rational. We have a health system with many vulnerabilities, but corruption and profiteering are not chief among them. Trust is a resource. But at any time, the public may no longer care to trust if they suspect that institutions no longer care for them.

Pinker, as his book would predict, deviates from his own standards of rationality when discussing issues close to his heart. He makes straw men out of the ‘cultural anthropologists’ and ‘literary scholars’ who ‘avow that the truths of science are merely the narratives of one culture’ yet ‘have their child’s infection treated with antibiotics’: a farcical presentation of those whose research argues that scientific knowledge is touched by the contexts in which it’s produced. Pinker demonstrates the availability heuristic when he states that ‘universities have turned themselves into laughing stocks for their assaults on common sense’ and are at the ‘forefront of finding ways to suppress opinions’.

The forefront? Really? He overstates the problem by the number of examples he can produce, prompted by his own stakes in this debate. A rational life also requires ‘epistemic humility’, a humility which Pinker is not always willing to extend to the social sciences and humanities. As a result, he oversimplifies the current challenges we face about knowledge — the suspicion of expertise, the bias in our data collection — which these academic disciplines work hard to explain and unmask.

Rationality reminds us that ‘good cognitive habits’ are a daily grind which is worth the effort. But beware the Professor Higginses of this world, exasperated by everyone else’s fallacies and fancies, while remaining comfortably blind to their own. We should follow reason, but not those voices — online and offline — shouting at us to be reasonable.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in