The row over racism at Yorkshire County Cricket Club has also shone a spotlight on anti-Semitism in the cricketing world. Andrew Gale, the Yorkshire head coach and former captain, has been suspended for having sent a tweet which said: ‘button it, yid’.

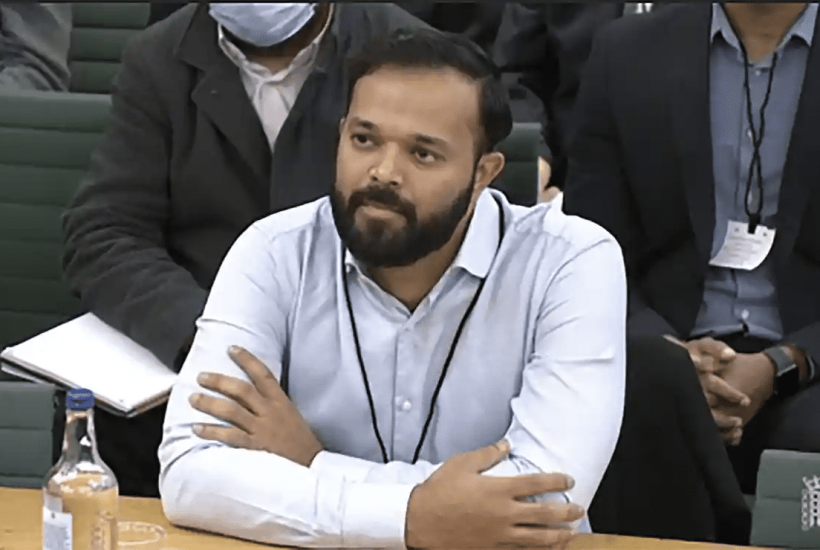

Azeem Rafiq, the former Yorkshire spin-bowler who blew the whistle on racism, was found to have sent a Facebook message in which he labelled a fellow cricketer as a ‘Jew’ for being reluctant to spend money at a team dinner, and went on to assert: ‘Only Jews do (that) sort of shit ha’.

The comedian Mike Yarwood once quipped: ‘I was doing the smallest books in the world. Famous Jewish cricketers, Australian etiquette, that kind of thing.’ Yet despite the absence of many top-level Jewish cricketers – or perhaps because of it – there’s a long history of anti-Semitism in the sport

Fast bowler Norman Gordon was the first openly Jewish South African Test cricketer. The distinguished advocate Sir Sydney Kentridge QC recalls that when Gordon made his Test debut, the South African Jewish community ‘were very proud that a Jew was playing for their country’. Not all shared that view. Gordon, who died in 2014 at the age of 103, told me that when he ran up to bowl the first ball on his Test debut, he heard a heckler in the crowd shout ‘Here comes the Rabbi!’. ‘Fortunately, I took five wickets in that innings’, said Gordon, ‘and that shut him up for the rest of the tour.’

Gordon was the leading wicket-taker on either side in the only Test series in which he played, against England in 1938-39. Many thought his bowling would thrive in England. In his autobiography, Sir Len Hutton stated that he had ‘little doubt that if the war had not intervened Norman Gordon would have made a big name for himself had he toured England’.

South Africa’s 1940 tour of England was cancelled because of the Second World War, and Gordon was not picked for the 1947 tour. Why not? Many years later, Gordon told me, ‘a friend of mine told me that he had heard from one of the tour selectors that (the South Africa and Sussex batsman) Alan Melville had told them not to select me as there might be anti-Semitism and unpleasantness in England and he thought it expedient to let me out of the tour. I am sure that my friend wouldn’t have told me if it wasn’t true. There was quite a bit of feeling about Jews even after the War in England.’

It was also widely believed that the reason why Percy Fender did not captain England was because he was thought to be Jewish. On his death in 1985, the sports writer Frank Keating said:

‘He played in 13 Tests – indeed, he should have captained England regularly, many said, but he knew he never would when he overheard an MCC president at Lord’s referring to him as ‘the smarmy Jew boy”.

Fender denied that he had a Jewish background or that it would have been held against him if he had. In the 1920s, however, cricketing authorities wanted England cricket captains who fitted the mould, who accorded with their preconceptions of what a captain should look like. Fender didn’t fit that mould for various reasons, of which perceived Jewishness may well have been one.

Out of a fear of anti-Semitism, a number of Jewish cricketers hid their heritage. Fred Susskind, who was educated in England but went on to play five Tests for South Africa on its 1924 tour of England, took pains not to publicise his Jewishness. Norman Gordon, who knew him well, told me that Susskind ‘was Jewish but didn’t profess to be Jewish, didn’t admit to it. The South African papers never mentioned he was Jewish.’

Sid O’Linn, who played both cricket and soccer for South Africa was in fact born Sydney Olinsky in 1927 in Oudtshoorn, a small town in the Cape where his father ran a kosher butcher shop. By changing his surname, Sid was able to pass himself off as a non-Jew of seemingly Irish, rather than Jewish origin.

Derek Ufton, who had played cricket with O’Linn for Kent and football for Charlton Athletic, told me:

‘Sid kept himself to himself. It was hard to get to know much about him. You have to remember that in South Africa at that time — he was from the Cape — you wouldn’t get into certain clubs if you had different blood in you.’

Anti-Semitism continues periodically to be reported among the cricketing establishment. In 1995, the commentator Henry Blofeld was censored when he stated that onlookers watching the match from the balcony of two buildings outside the ground at Headingley were in ‘the Jewish stand’, because they had avoided having to pay to watch the match: he later admitted that he ‘was mercifully not cast into the outer darkness I probably deserved’.

Azeem Rafiq’s bigoted messages suggest that anti-Semitism is still present in top-level cricket. Yet as a victim himself of prejudice, Rafiq’s response to his own exposure gives hope for the future. He promptly issued an apology, said he was ‘ashamed’ and committed himself to learning about the Jewish faith and gaining an understanding of anti-Semitism. The game could learn a lot from that.

<//>

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Daniel Lightman is a QC and the co-author of Cricket Grounds from the Air

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in