On 26 October, Cricket South Africa (CSA) directed all its players to take the knee at the T20 World Cup or sit on the bench. Wicket keeper and impact batsman Quentin de Kock pulled out of the day’s match against West Indies. His stance sparked moral outrage on both sides: against the threat to constitutionally protected free speech and expression by a compelled gesture of solidarity versus the need for solidarity in the fight against all forms of discrimination, but especially racial. On the 28th, having thought it over, de Kock agreed to take a knee, noted his step-mother is black and his half-sisters are coloured and apologised for the confusion and disharmony caused by his pull-out. In a thoughtful interview on 9 November, the (black) captain Temba Bavuma said: ‘We can all go out there, raise our fists, go on the knee, but if deep down in the heart, you’re not really for the cause and it doesn’t show in your everyday behaviour then I guess it brings into question the authenticity of it all’. He added: ‘Our country has big, big, big problems and that’s where the energy should really be spent’.

That’s the crux of the problem. The gesture no more proves you’re anti-racist in behaviour than refusing it denotes racism. An employer has no right to intrude into matters of personal conscience, prioritise among the challenges confronting a country and compel employees to join in solidarity with its social and political choices regardless of the possibly troubling origins and associations of the gesture. Like other manifestations of ‘solidarity’ with oppressed and marginalised minorities – critical race theory, gender pronouns, gender affirmation – taking the knee is in practice proving extremely divisive. It’s inextricably associated with the BLM movement whose original agenda called for the destruction of the family unit and transformation of society.

While those who want to feel good indulge in gesture politics like that mandated by CSA, others prefer to view cricket’s current reality in the wider social and political context and to prioritise practical action over symbolic statements. All you need to do is look at cricket’s playing fields around the world, all the way from club and county level through first-class provincial and international matches. T20 leagues, both men’s and women’s, are especially prominent, where players from all nationalities, ethnicities and religions share dressing rooms as teammates. On Sunday 8 November, for example, in a Women’s Big Bash League match, the diminutive Indian spinner Poonam Yadav was mobbed and lifted aloft by her jubilant Australian teammates after taking the wicket of star Indian opener Smriti Mandhana. WBBL matches are being broadcast in India both because Indians are cricket mad and also because so many Indian stars are playing in the league this year. That one image of the effervescent celebration of camaraderie will have done more to promote inter-racial harmony and goodwill than any number of taking the knee theatrics.

Or consider India’s iconic captain Virat Kohli with a mind-boggling social media following (45 million on Twitter, 164 million on Instagram). A pre-tournament favourite, India suffered two early setbacks going down to heavy defeats by Pakistan – its first win against India in a World Cup format – and New Zealand that knocked India out in the preliminary rounds. While Kiwis took the knee, the Indian openers remained standing at ease at the crease. In the Pakistan match India’s pacer Mohammad Shami leaked runs and was heavily trolled by a vicious social media mob that attacked him not for having an off-day but for being a Muslim. In the post-match interview, Kohli was generous in his praise of Pakistan’s performance. On 30 October a visibly angry Kohli said Shami had often won matches for India and attacked the trolls in forceful and robust language that’s been conspicuously missing from PM Narendra Modi’s vocabulary. Kohli spoke out despite knowing he’d provoke a backlash. On 10 November police arrested a man for rape threats against Kohli’s 10-month-old daughter, that’s how sick and cowardly these idiots are. In the 2019 ODI World Cup in England, Indian fans booed former Australian captain Stephen Smith for his role in Sandpapergate in South Africa. Kohli first shushed them into silence with finger to lips, then with hand gestures led them into applauding Smith. The defence of Smith and Shami might well be Kohli’s finest legacy as a true leader of men.

There’s similarly contrasting examples in US politics of Kamala Harris and Winsome Sears. Harris thinks of blacks and women as grievance-carrying permanent victims of a systemic oppressor, America. There seems to be no social, political and economic issue that Harris cannot racialise, including trees to be tracked by NASA satellites. Tony Shaffer, a former Defense Department official, tweeted, ‘This woman is a complete hack – and if this is not an act, she is also a moron’. Born in the US to comfortably middle-class immigrant parents who were both professors, Harris blamed the implosion of her campaign for the Democratic nomination on gender and racial prejudice, despite Obama’s election and re-election. Having attacked Biden for supporting racist policies during his long Senate tenure and savaged Brett Kavanaugh during his Supreme Court Senate confirmation hearings for sexual assault allegations that were more distant and less plausible than against Biden, Harris proved her inauthenticity in becoming his running mate and Vice President – and is helping to sink the administration in the polls.

Sears holds black women are empowered with agency in a land where dreams can come true. In a powerful victory speech on being elected Virginia’s first woman and black as Lt. Governor on 2 November, the Jamaican-born Sears recalled her father’s arrival in the US in 1963 with just $1.75, taking any job going and putting himself through school in pursuit of the American dream. Noting the end of restrictions on blacks since 1963, she said: ‘In case you haven’t noticed, I am black, and I have been black all my life’. In words that are music to the ears of a professor, she credited education as the pathway out of poverty.

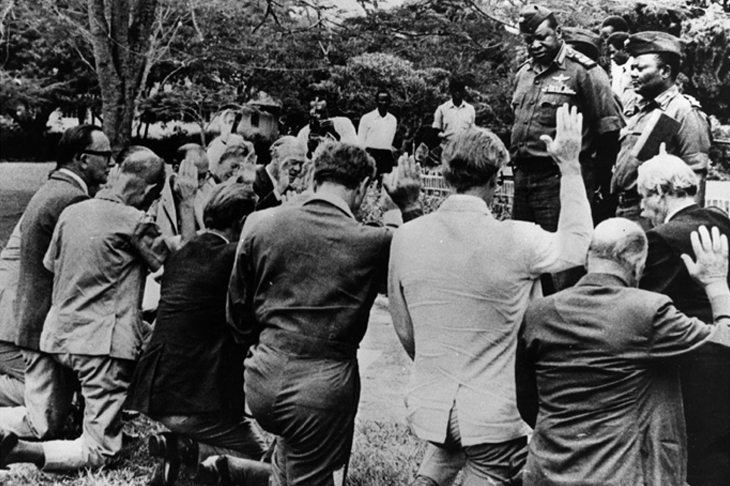

The photo above shows fourteen whites kneeling before Idi Amin in Kampala, Uganda in 1975. Colin Kaepernick was punished for taking a knee during the US national anthem before football games in 2016. The consistent and sensible approach surely is to leave it to the discretion of the individual athletes, neither banning nor mandating politically charged gestures.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in