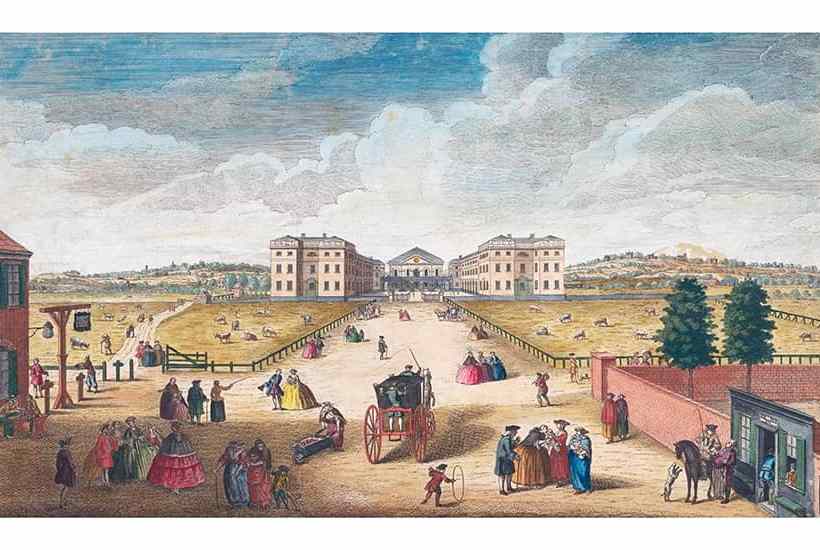

Rose Tremain’s 15th novel begins with a favoured schmaltzy image of high Victoriana: it is a night (if not dark and stormy, then certainly dark and wet) in the year 1850, and a baby has been left at the gates of Victoria Park. Then we have an uncanny detail: the baby is sniffed out by a pack of wolves, one of which bites off her little toe. Thankfully, a police constable finds her and walks through the night to Coram’s Fields to deliver her to the Foundling Hospital. From there she is sent to be fostered by a loving family on a farm in Suffolk for six years, only to return to the Hospital for a childhood of cruelty and abuse at the hands of the staff. We have already encountered her working as a wig-maker by day and dreaming at night of her execution by hanging.

Her crime is murder. This proves a weak drive for the narrative, however, as the novel moves at such a muddled clip, flitting back and forth in time, that the plot is a series of anti-climaxes. Lily’s childhood is intercut with her life as a young adult, but the former is elided to such an extent in the latter that its primary purpose seems to be to demonstrate that Tremain has done extensive research on the workings of the Foundling Hospital, its affiliated fostering system and the practice of stone-picking.

The novel is packed with treacly images and cliché. Consider, for instance: ‘She had no words anymore, only a feeling of sorrow and despair unlike anything she had ever known’; and ‘they clung together, crying and rocking to the rhythm of their broken hearts, until at last they were still and the nurse returned to snatch at Lily’s curls and pull her away by her hair’. Supposed seven-year-olds speak with a queasy maturity (‘It’s too painful for her’; ‘You’re meant to be sisters of mercy’). An eight-year-old hangs herself with a hand-knitted scarf 17ft long.

This is pulpy, mawkish pastiche veering on the penny dreadful, more Lemony Snicket than Charles Dickens. In what’s billed as a ‘tale of revenge’, the abuse that merits Lily’s crime is stuffed in at such speed it feels almost flippant, and the murder itself fails to hold the whole taut. Add to this a bizarre, para-paedophilic love plot and the result is a confused, disappointing novel.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in