What’s going to happen?

Is everything going to be ok?

What should we do?

Predicting the future has always been fraught with difficulty. One need only look to predictions from the past for how misguided they can be:

“The battle to feed humanity is over. Hundreds of millions will starve to death” Paul Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb, claimed back in 1968.

“If current trends continue, we will reach peak oil by 1995.” Marion King Hubbert, a Shell Oil geologist, dolefully intoned in 1974.

The fact that most health problems are caused by overeating rather than malnutrition and that crude oil is still ubiquitous is proof of how fallible our predictions are.

Still, looking to the future is important. We must at least try to guess which way the wind will blow and adjust our sails accordingly.

One such prediction relates to energy. Where will we get it from in the future?

Leaving aside whether global warming is a credible threat, there are increased calls from policymakers, scientists, and industry leaders that a growing percentage of Australia’s energy needs be sourced from renewables.

Will this be the case? How can we begin looking at such an issue?

Political scientists have frameworks that can be useful.

Marko Papic, a PhD from the University of Texas, posits that policymakers do not make decisions on what they want to do. Rather, they make decisions on what they are forced to do by the restrictions imposed on them by the situation at hand.

Ideology may be ever present in political discourse, but final decisions are made only after considering the political reality.

Papic sets this theory to work often. Not in a dusty library on a university campus. But for hedge fund managers who stake millions of dollars based on his model.

Papic’s theory is known as the Constraints Based Model and considers geopolitics, the economy, the average voter, and other factors that help to shape future decisions. It is these constraints, rather than the whims and desires of ideological politicians, that dictate the future.

Papic’s position as a money maker rather than a pundit or adviser is perhaps most telling. His motive is to make the right investment decisions and is therefore completely transparent. He has no reason to conflate what he wants to happen for what is likely to happen. He’s only trying to make a quid.

For instance, Greece’s Syriza Party may have billed itself as an anarchistic far left faction that wanted to leave the European Union during 2010’s Eurozone crisis. But when it came to power, Greece’s reliance on the rest of Europe to subsidize its economy coupled with the fact that most Greek voters wanted to remain in the community made ‘Grexit’ impossible. Even anarchists must live in the real world. And so it was that Greece remained in the EU.

Seven years later, the United Kingdom, faced with a similar issue chose to leave the EU. Why? The UK’s economy was far more dynamic than Greece’s. It could weather the storm of ‘Brexit’ with minimal damage. Furthermore, after a savvy campaign run by UKIP’s Nigel Farrage, most Britons decided it was time for the UK to leave the EU and voted accordingly. And so it was.

It is these two constraints: the economic realities and the opinion of the average voter (what Papic calls the Median Voter) is what forms the basis of the theory.

So, what does this mean for energy policy?

If we’re to look at the Median Voter in Australia, it’s clear that they demand action on the perceived climate issue. Concerted efforts by the media and academia have convinced Australians that the sky is falling.

According to polling done by the Lowy Institute, sixty percent of Australians agree that global warming is a serious and pressing problem. Fifty-five percent believe that the government should be doing more to reduce carbon emissions.

It’s tempting to look at this data and assume that the government of the day, regardless of their stripes, will have to bend to the will of their voters or else face political oblivion. Afterall, the government is the servant of its people.

But the opinion of the median voter is only half the story. The economic constraints of the situation are also important.

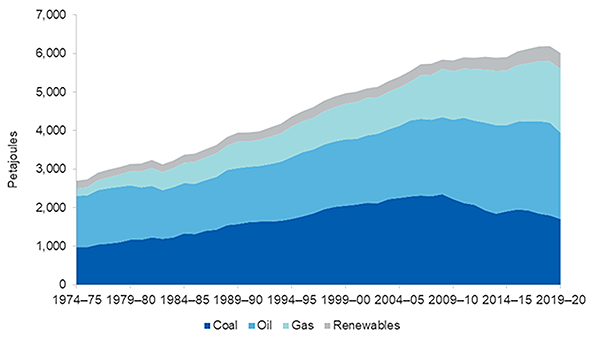

Currently, fossil fuels make up over ninety percent of Australia’s energy consumption. The much-vaunted renewables sector only powers seven percent of Australia. This number has changed little over the last forty-five years, despite the generous subsidies afforded to the industry by the Australian taxpayer. A figure that’s expected to reach $2.8 billion by 2030.

And here lies Australia’s current gridlock. An electorate that, rightly or wrongly (but probably wrongly), demands immediate and drastic action on the climate crisis led by governments that have their hands tied by the economic realities of the day. If we stop using fossil fuels today, our economy and our standard of living will tank tomorrow. There’s no other way of putting it. Renewable energy is not cheap enough or efficient enough to sustain our way of life. When you can’t cook dinner or keep the lights on, suddenly rising sea levels don’t seem so important.

When former US Vice-President Al Gore won an Academy Award for his PowerPoint Presentation, ‘An Inconvenient Truth’ in 2007, climate alarmism really started ramp up. It’s not a coincidence that since that time we have faced a revolving door of prime ministers – a total of six since the film was released.

Put the needs of the environment over the needs of the economy (think Gillard’s carbon tax) and voters will show you the door. Put the economy over the climate (think Abbott declaring ‘coal is good for humanity’ while opening a new coal mine) and voters will show you the door.

The climate question has made the Prime Ministership a poison chalice for even the deftest political operators.

Is there a way forward from our current political impasse? Can we balance the economy with the demands of voters?

The answer is yes. The answer is nuclear power.

In the early 1980s, France made a commitment to nuclear energy. In so doing, it secured its energy future and economy while becoming the lowest per capita carbon emitter in the European Union. Furthermore, it’s a net exporter of electricity which adds 3 billion euros to its bottom line every year.

If a nation that’s smaller than New South Wales with no significant uranium reserves was able to use nuclear to generate seventy per cent of its energy needs forty years ago, why can’t Australia do it today?

The answer lies with the median Australian voter. Sixty two per cent of them are either strongly against or somewhat against building nuclear power plants to cut carbon emissions. They want action but would like it to come from technology that does not work. It’s akin to wanting the cure for your skin condition to come from a witch doctor instead of a dermatologist.

So, what’s going to happen? What’s my prediction for the future?

A lot more bickering. A lot more indecision. A lot more unrealistic demands from voters. A lot more hand wringing from policymakers.

Unless, of course, we as a nation accept the fact that nuclear energy is our only way forward.

Afterall, the best way to predict the future is to create it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in