Given the ability of Covid-19 to make fools out of everyone, it is not entirely fair to single out an opinion piece penned by Christina Pagel and Martin McKee, members of the self-appointed ‘Independent Sage’ committee on 7 October. But it sums up an attitude which was common just seven weeks ago. ‘England, not for the first time, is the odd one out in Europe,’ they wrote. England had recklessly abandoned Covid restrictions in July, relying on vaccines alone to keep the country open. In contrast, our European neighbours were sensibly employing a ‘relatively light set of extra measures’, such as vaccine passports, to keep infections much lower than England’s. ‘They are demonstrating that there is a way to be open while keeping cases low… It works. And we should be doing it.’

That does not look like such a clever analysis now. Mainland Europe is once again the epicentre of the pandemic. Austria is back in lockdown and many countries face proposals for compulsory vaccination. In Austria, the number of new infections has doubled every fortnight since early October. Daily deaths are higher than they were during the first wave of Covid in the spring of last year. In the Netherlands, where police ended up firing at anti-lockdown protestors in Rotterdam, the autumn spike in infections is just as sharp as in Austria. Germany’s numbers are rapidly catching up. Sweden is offering hospital places to Romanians whose own healthcare system cannot cope with the surge.

What is remarkable about this wave is how quickly it has erupted into a culture war over vaccination. On 8 November, Austria’s new chancellor, Alexander Schallenberg, announced a vaccine passport scheme of the kind already in operation in France and several other countries. Four days later he crossed a line which no other European leader had then dared cross: he announced a lockdown exclusively for the unvaccinated, to take effect from Monday 16 November. A week after that, the country was in full lockdown. Schallenberg then reached for a lever which had been rejected by his youthful predecessor, Sebastian Kurz, who was removed from office in October over bribery allegations: compulsory vaccination, enforced with the threat of €3,600 fines for refuseniks. Even Xi Jinping’s regime rejected compulsory Covid vaccination when several regional Chinese administrations flirted with the idea in the spring. Indonesia, Micronesia and Turkmenistan are the only countries, so far, to have introduced a Covid vaccine mandate for adults.

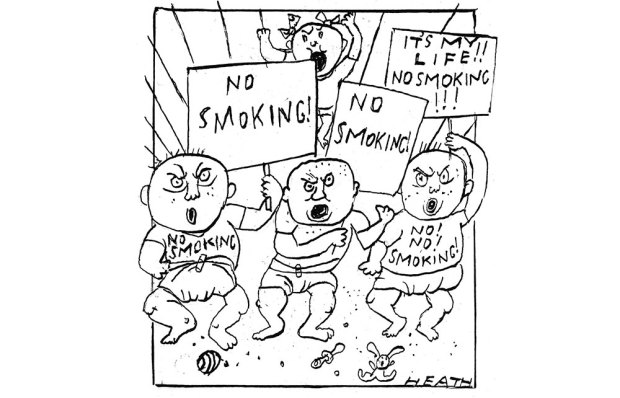

Schallenberg, a dull functionary whose chancellorship might otherwise have gone unnoticed by the outside world, has acquired instant notoriety, which surely he must have foreseen. Within hours, 35,000 people were out on the streets of Vienna, and copycat protests were being held around mainland Europe as their governments, too, discussed the idea. In Brussels, a crowd of 35,000 were repelled by water cannon, but not before they had damaged a police car and thrown objects at the windows of the European Commission.

Much has been made of the involvement in Austria of the right-wing Freedom party, which has been pushing against vaccination for months and whose leader, Herbert Kickl, would have been heading last weekend’s protests had he not tested positive for Covid and obediently put himself into quarantine. Yet to portray Austria’s — and Europe’s — anti-vaxxer movement as a right-wing phenomenon misses the point.

Compulsory vaccination in Austria is also opposed by the newly formed Menschen–Freiheit-Grundrechte (People, Freedom, Rights or MFG party), formed this year specifically to push back against Covid measures. In regional elections in Upper Austria in September, the party won 6.4 per cent of the vote, securing seats in the regional parliament. But it cannot be pigeonholed as a right-wing party: an analysis revealed that while 30 per cent of its supporters had previously voted for far right parties, 30 per cent had voted for moderate conservative parties, 16 per cent for socialist parties and 12 per cent for the greens.

Europe’s anti-vaxxer movement has swept up libertarians on the right and Mother Earth-types on the left. While some have identified a link between vaccine hesitancy in the old East Germany and concentrations of voters for the right-wing AfD party, Germany has long been a hotbed of alternative medicine, with three-quarters of German doctors offering such treatments for people who favour them over drugs that have been proven in clinical trials. It should come as no surprise that a significant minority of Germans have rejected Covid vaccines, too. One thing, though, is for sure: enforcing vaccination by law will solidify support for minor parties which, like the AfD, draw their support from people who feel they have been pushed to the margins of society.

It suits many in government to write off vaccine refuseniks as idiots brainwashed by anti-vaxxers. Justifying his decision to fire unvaccinated care-home staff, the Health Secretary Sajid Javid suggested that they had been ‘listening to these ridiculous theories on the internet or on social media’. But do all people who have declined the vaccine really fit into this category? A University of Erfurt study revealed that 80 per cent of those refusing to be vaccinated said they had no fundamental objection to the vaccine; they just wanted time to weigh up the risks and benefits.

Given that their own government restricted the AstraZeneca vaccine to the over-sixties on the grounds of a rare blood-clotting disorder, it is hardly unreasonable that some Germans should feel wary of taking vaccines which have been developed far quicker than most. The Erfurt findings reinforce an Office for National Statistics (ONS) study which found that only 8 per cent of those who have declined the Covid jab in Britain did so because they had an objection to vaccines in general; most were simply worried about potential side effects. You can argue that they have made the wrong decision — that on the balance of risks they would be far better having the vaccine — but that doesn’t make them victims of anti-vaxxer propaganda.

The idea that low uptake of vaccines in some European countries can be blamed on the far right is further undermined by statistics showing vaccine hesitancy is much higher among some ethnic groups. In February, the ONS found that 44 per cent of ‘black or black British’ adults were hesitant, compared with just 8 per cent of white adults. It is hard to imagine that many have been influenced by the far right.

Nor, of course, do you need to be worried about the Covid vaccines to oppose the principle of compulsory vaccination. The notion of a government forcing medical treatment on citizens is deeply objectionable to many who have chosen to be vaccinated. This argument particularly resonates in Germany and Austria, where the Nazis and the communist regime of East Germany both made vaccination compulsory in some instances. And that’s not to mention more recent memories in Sweden, where compulsory swine flu vaccines led to a slew of lawsuits from those who later claimed to have been harmed.

There is a utilitarian argument that when it comes to vaccination against infectious disease, the rights of the individual ought to be suspended for the benefit of the many. Yet there is a big hole in this argument when it comes to Covid: while the vaccines used so far have proved themselves to be highly effective at preventing serious illness and death, they are much less good at preventing infection. As pointed out in a letter in the Lancet last week by Günter Kampf, an epidemiologist at Greifswald medical school in Germany, 55 per cent of recent Covid cases among Germans over 60 have been in fully vaccinated individuals. Compulsory vaccination, or locking down the unvaccinated, might reduce risk and reduce hospitalisations and deaths but they will hardly take all risk out of circulation — the virus will still spread among large numbers of people. Kamf was especially critical of people lazily asserting that we are now in a ‘pandemic of the unvaccinated’; which he argued is fundamentally untrue.

A word ought to be said about another — surprising — brand of anti-vaccination opinion: that expressed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) against booster jabs. As recently as August the body put out a statement opposing plans by Britain and other western countries that were already planning third doses. ‘Offering booster doses to a large proportion of a population when many have not even received a first dose undermines the principle of national and global equity,’ it stated. By September, the WHO had started to change its mind. Now that the virus has returned with a vengeance to Europe, we don’t hear much of that argument anymore. On the contrary, we hear only complaints that countries are not progressing fast enough with their booster programmes.

Booster jabs is one area in which Britain is ahead. Boris Johnson defied some of his scientific advisers in removing Covid restrictions in July and defied the WHO in planning a booster programme. Yet his decision to rely on vaccines rather than vaccine passports looks at the moment to be vindicated, as Britain is entering winter with many more older people freshly jabbed.

It would be foolish to boast too soon, but Johnson’s policy of opening up society in the summer — exposing those who had declined to be vaccinated to the virus at a point when hospitals were under little pressure — might turn out to have been a better move than keeping restrictions, which in Europe succeeded only in delaying another Covid wave until the autumn. The latest ONS antibody study found in the week beginning 1 November an estimated 93 per cent of UK adults were carrying antibodies to Covid-19, suggesting that Britain has a high level of immunity, gained either through vaccination or recovery from the virus.

The relatively high levels of infection over the summer and early autumn may turn out to be what defends us against the surge being witnessed on mainland Europe — as well as the public disorder that goes with it. We are indeed the odd one out in Europe, but not necessarily in a bad way.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in