Thirty years ago the Soviet Union was guttering to its close. Those of us who were there remember the exhilarating hope, the apprehension, the illusion. For everyone else it is a distant echo.

Russia was always likely to lose the Cold War competition with America. It was unmanageably large, too poor and too reliant on too few products. Stalin’s bloody grip had enabled the Soviet Union to defeat the Germans at a terrible cost to his people. When he died in 1953 his system entered a protracted agony.

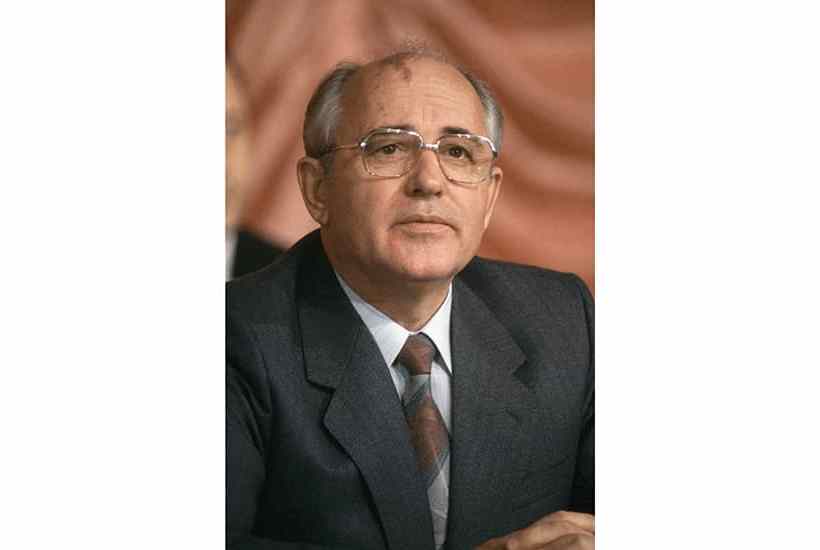

Over the next decade Nikita Khrushchev tinkered with half-baked solutions. They misfired, and he was overthrown by the hard men in the party, the KGB, and the army. His more cautious successors managed to equal America’s military might. They had successes among the uncommitted nations. But the concessions they made to their consumers could not compete with the ideas, the music, the films and the jeans that carried American influence throughout the world. Soviet teenagers and intellectuals looked to the West, convinced that its streets were paved with gold and freedom. Doubts grew even among the bureaucrats and the generals. In March 1985 the old men of the Politburo — conservative, but not stupid — chose Mikhail Gorbachev to put things right.

Gorbachev was open, optimistic and more charming than any previous Soviet leader. At first he was wildly popular abroad and, though they now forget it, among his own people too. He believed that the system could be saved by cutting the crippling burden of defence expenditure, reaching out to the Americans to wind down the Cold War, reforming the economy and introducing a degree of democracy. He had some bittersweet successes and some devastating failures.

He and President Reagan did begin to get the nuclear confrontation under control: but on every issue he faced America’s superior negotiating clout. Among the Soviet Union’s unwilling partners in Eastern Europe and the subject peoples within the Union itself, his tinkerings ignited the hope of independence. The economy nosedived.

By August 1991, Gorbachev’s credit was in tatters. The hard men tried to oust him, as they had ousted Khrushchev. They failed ignominiously, because even the military feared civil war. In December, Boris Yeltsin, his implacable rival, declared that the Soviet Union had been replaced by Russia under his command. The subject peoples raced for the exit. Gorbachev resigned.

Yeltsin took decisive action on the economy: shops emptied, social services broke down, people stopped getting paid, and he himself declined into incoherent alcoholism. Vladimir Putin took over in January 2000. He restored Russia’s prestige abroad and turned Yeltsin’s reforms towards prosperity at home. Most of his people welcomed that. They weren’t too worried by his authoritarianism: they had come to regard democracy as a western sham designed to destroy their country.

That is an oft-told story. But basic questions remain. Was the collapse inevitable? Was it all Gorbachev’s fault? Should Russia have adopted state capitalism, Chinese-style? Could a more generous American policy have ensured a better outcome?

As long as people write history the debate will continue. Vladislav Zubok has made many distinguished contributions to it already. His latest book draws on new details from the archives and many other sources (including my diary, which mixes useful facts and uncomfortable misjudgments). His narrative is limpid, his judgments balanced, all backed by meticulous research. As a Russian, he brings a usefully different viewpoint. He believes that by the time Gorbachev took over, the Soviet elite was already paralysed by doubt. The men who tried to overthrow him had no better plans than he did. The Chinese model — modest authoritarianism combined with radical market liberalisation — was available. But the ‘hapless captain’, as Zubok calls him, had neither the courage nor resolution to preserve the Union and compel reform, if necessary by a ‘resolute use of force’.

I am sceptical. No one man could have solved the existential problems of the Soviet Union on his own: that is a task for generations. Gorbachev had many faults, but his was an honourable failure. He opened up the country. He refused to shed blood. He contributed decisively towards damping down the nuclear nightmare. For that Russians too can be grateful.

As for the Americans, victory in the Cold War had left them free to promote their interests as they saw fit. They tried to build a liberal Russia, as they had rebuilt defeated Germany. That was good policy; it was never intended to recreate a rival. They enlarged Nato, bombed Serbia, invaded Afghanistan and dismantled the arms control system with little regard for Russian concerns. But the attempt to re-engineer Russia’s politics was beyond even their powers. Only the Russians themselves can do that: the failure so far to overcome the burden of the past and build a workable democracy is their failure.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in