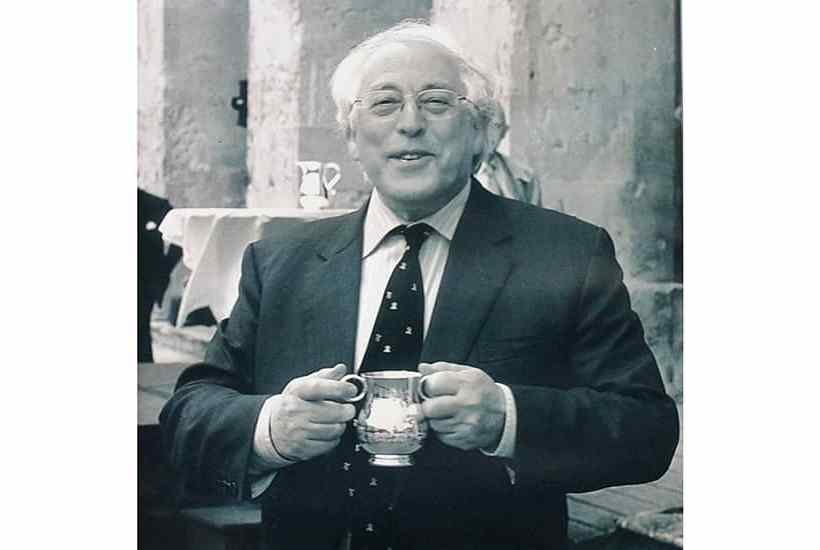

I’m not sure how many readers know the name of Anthony Smith, who died on Sunday aged 83, but a fair number will. He spent almost a decade at the BBC, helped start Channel 4, directed the British Film Institute, chaired many committees and for 17 years was president of Magdalen College, Oxford. But while not every reader will know him, you are lucky if you know the type: that rare person whose passion is helping other people — the type, in other words, who makes the world work.

I first met him when I was a precocious schoolboy of 16. I had asked permission from Magdalen’s librarian to look at some manuscripts for a book I was researching. Tony was clearly alerted to this and made the effort to introduce himself and take me for a walk around the college grounds. He asked me what I intended to do in the coming years, and I said I had a vague idea of applying to Cambridge. Although Tony stressed that he himself could do nothing to facilitate the move, might I not consider applying to Magdalen?

In due course I did, and turned up in my first year with a finished book. On its 20th anniversary reissue last year I noted that it could never have happened without Tony. He introduced me to a friend who was doing some literary agenting, and before long Tina Brown was flying in from New York to acquire the rights for Miramax. Tony made it clear to me that Tina Brown was a big deal and I should try to shine at this meeting.

He was good at preparing you like that. When I first did some public speaking he told me: ‘There is basically only one rule in public speaking. Never appear on a stage before, with or after Christopher Hitchens.’ A lefty himself, Tony had grown up in terrible poverty in wartime Wales. At one stage his mother, sister and he all lived off the meagre allowance that his elder brother sent back from his scholarship money at Oxford: a place to which Tony followed him in due course.

Rather than lament his past, or boast about how he had made good, Tony used his energies to help as many other people as possible to make good too. Whenever kings, ministers, presidents or celebrities visited his Magdalen lodgings, he always made sure it was the students who got the benefit. Paul McCartney, Richard Attenborough and Boris Yeltsin, for example, were brought to the student bar.

On one famous occasion Princess Margaret came to the college. Tony had recently witnessed her at John Paul Getty’s use some exquisite food as an ashtray. Realising she could never be satisfied, he decided that she should eat the same grub as everyone else. She did, and after dinner Tony invited her and a group of students back to his lodgings. Some played for her, others danced with her, and when she got into her car in the early hours the unimpressible Princess was heard to say simply: ‘That was fab.’

Tony never married, but was one of those people who pour their passion into their friendships and especially into the cultivation of young people. At Magdalen he spent every hour working for the students and anyone else he came across. (I once met a builder who Tony had effectively raised himself.) At Thanksgiving he would cook a great feast for any Americans who were around. At Christmas he would cook for students who didn’t have families to go to.

Sometimes his generosity involved introducing people to people he thought they should meet; sometimes it involved introducing them to an experience he thought they should have. He once took a group of us to Ronnie Scott’s to watch an astoundingly drunk George Melly. Another time he told me what to say to a director if their film was a stinker (‘You’ve done it again!’). And he relayed the most charming compliment he’d ever been given. Isaiah Berlin after a dinner: ‘You will ask me again, won’t you?’

Despite his bewildering array of friends, he never dropped a name. If anything he withheld them. Some years back he and I were at a dinner where some bore started talking about Seamus Heaney, who had just died. Nothing could make him stop. Eventually the bore said: ‘Did you ever meet Heaney, Tony?’ ‘He lived with me for five years,’ said Tony, with unusual testiness. He loved the time when Heaney was Oxford Professor of Poetry and stayed at the lodgings. One day they found a bird stuck in the chimney. ‘What do we do?’ Tony asked. ‘Now I may be a nature poet,’ replied the future Nobel laureate, ‘but I never touch the stuff.’ Together they eventually pulled out by its foot what turned out to be a dove, took it to the window and let it fly across the quad.

Tony was not treated by the college as well as he should have been, given everything he had done. Yet he was a stranger to bitterness. He also missed all the major honours he should have received. The last Labour government denied him an expected peerage when Gordon Brown picked an unjust fight with Magdalen over student access. Tony defended his college and its superb access scheme to the hilt, and Brown never forgave. Five years ago one of our friends was knighted, and mentioned that he had no tailcoat suit to wear to the palace. ‘Oh, I have one,’ said Tony. ‘Borrow mine.’ After the event I asked Tony about it and he joked that at least his tailcoat had been knighted, just without him in it.

No one has ever devoted themselves more successfully than Tony to quietly fund-raising for this country’s institutions and working for scholarship schemes for students who needed help most. Right to the end a stream of people would visit him in London for advice. Whether it was a former chancellor or a student starting out, the chances were that they were in the area to visit Tony.

The obituaries will probably say that he had no children. That isn’t true. He had thousands of us.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in