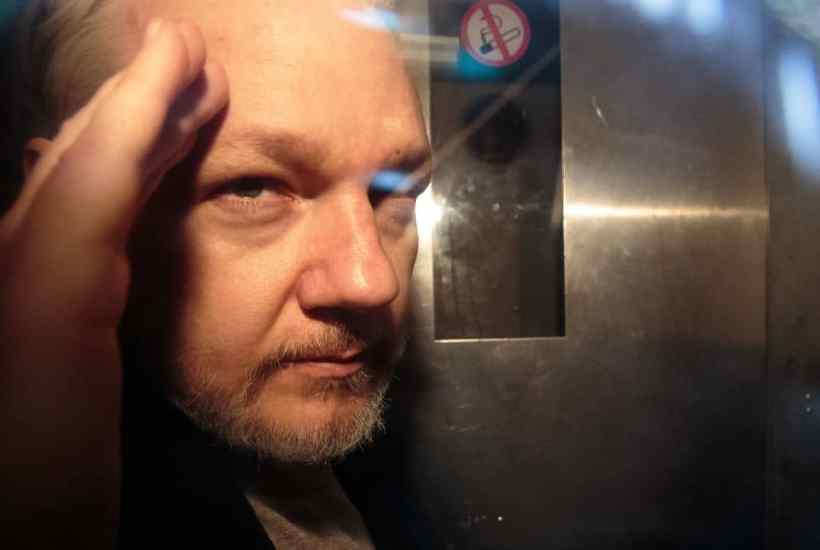

Julian Assange is facing extradition after the high court ruled there is no legal impediment to him facing espionage charges in the United States. The decision would seem to justify the fears that the WikiLeaks founder and his supporters have long harboured: that the UK has essentially served as a holding pen until such time as a legal mechanism could be found to enable his dispatch to the US.

Assange has always believed that the US would not stop until it had exacted retribution. His former lawyer and now fiancee, Stella Morris, said after the latest ruling that they would appeal, if possible, to the UK Supreme Court. The extradition case now returns to Westminster Magistrates’ Court where it began. It remains to be seen if there will be further opportunities to appeal.

Whether or not you support Assange, however – and he is certainly a figure who attracts strong opinions for and against – there are compelling reasons why his extradition would be a travesty, not just of justice, but of the ‘values’ the UK repeatedly claims it represents.

The case presented on behalf of Assange, which has now been rejected, rested on his mental state and the risk that he might take his life if subject to the special regime of a US top security prison. The narrowness of this case proved its weakness. And the judge found for the US, having secured assurances that he would not face any special regime while in a US prison and would be able to serve any sentence in his native Australia.

The first qualm would have to be how far those US undertakings can be trusted. Once Assange was transferred to US jurisdiction, he would be beyond any protection those UK court undertakings could give. It is not hard to imagine circumstances where they could be breached.

A second relates to the US justice system itself. Once a defendant is in the system, it is common practice for US prosecutors to threaten the defendant with a mammoth sentence in the effort to obtain a guilty plea – a plea bargain – they can notch up as a success. Unsurprisingly, this can lead to miscarriages of justice, especially where – as in Assange’s case – there are likely to be elements of emotion and vengeance that commonly attach to what would be presented as treachery.

Which leads to a third, and perhaps the most compelling, reason why Assange’s extradition should be resisted. The US initially applied for Assange’s extradition from the UK on the far less serious charge of computer misuse. Part of the point here might be that courts will often not extradite people on espionage charges, which they may regard as political. Assange and his lawyers always saw the lesser charge as a ploy to get him to the US, after which the charges could be augmented or changed at will.

It was only after time ran out on Sweden’s attempts to extradite Assange that the US upped its charge-sheet to add 17 charges of espionage. But the argument is as valid now as it was when the US did not include it in its initial application. The secrets that WikiLeaks placed in the public domain are highly political. They serve to discredit sections of the US military and US diplomacy. Does that make their release a crime? Should the UK be protecting the secrets of the US, major ally or not?

As presented, the espionage charges seem flimsy. It is hard to see how a US court could make them stick. The precedent consistently cited here is that of the so-called Pentagon Papers, published by the Washington Post and the New York Times in 1971. The Post, which could have been bankrupted or closed, after its publisher, Katharine Graham, took the decision to ‘publish and be damned’, was vindicated in what has been seen as a landmark ruling that protects a free press.

According to this, someone who divulges secrets they are contracted to keep has committed a crime, but anyone who subsequently publishes it or facilitates its publication has not, if its release can be judged to be in the public interest. This crucial distinction is one that endures to this day on both sides of the Atlantic. This is a vital protection for investigative journalists everywhere. If either the receipt or the publication of secret information in itself becomes a crime, the balance will have shifted significantly in the favour of the powers that be and against people’s right to know – and the journalist’s right, even obligation, to tell them.

These are all factors that should count against the UK extraditing Julian Assange to the US – and why, in the end, the UK Supreme Court, might rule against it, if the case were to get that far. But the notoriously lop-sided nature of the UK-US extradition agreement makes it easier for the UK to grant US requests than the other way round. There is also, of course, the equally lop-sided political and diplomatic relationship between the two countries, where refusing extradition to Assange could be seen as a tantamount to a hostile act. The auguries do not look good.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in