China reacted to the news of the US government’s diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics with predictable fury — a foreign ministry spokesman described it as a ‘naked political provocation’. He then added that US officials had jumped the gun because they had not even been invited. That seemed like a bit of added petulance, but it is entirely in keeping with China’s growing mood of self-isolation — a mood that is beginning to have some bizarre and dangerous consequences.

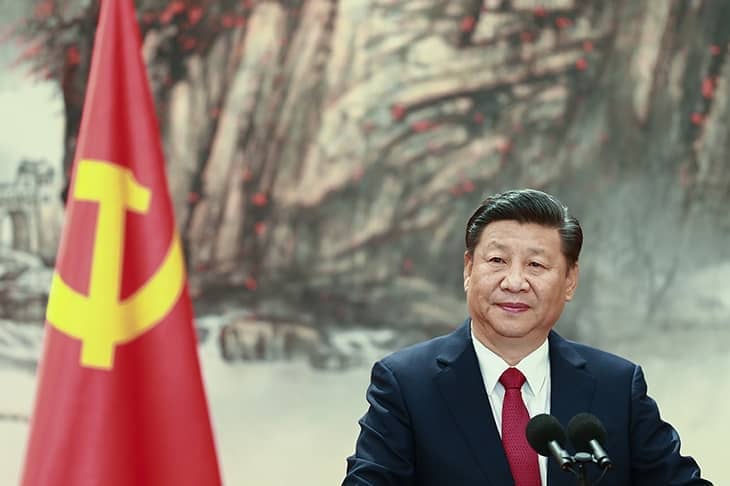

The Chinese Communist party has always been a paranoid organisation, with a deep suspicion towards the outside world, but President Xi Jinping has taken this to new heights. Western policy-makers are alarmed. Richard Moore, the new head of MI6, alluded to this in a speech last month when he warned: ‘Beijing believes its own propaganda about western frailties and underestimates Washington’s resolve. The risk of Chinese mis-calculation through overconfidence is real.’

Moore did not explicitly name Taiwan in his speech, but the risks of China’s bunker mentality for the island are evident. Last month alone, the Chinese government was twice forced to deny that it is about to go to war over Taiwan. ‘To concoct such military-related rumours on certain online platforms is extremely irresponsible and illegal,’ thundered the Defence Ministry.

The rumours ricocheted around Chinese social media after the Commerce Ministry urged citizens to stockpile rice, noodles, vegetables and other essentials for the winter, and then again after reports that the military was re-enlisting former soldiers. The government insisted the stockpiling guidance was a Covid-19 precaution and flatly denied the reports of re-enlistment. China’s heavily censored online world is a febrile place at the best of times, but these rumours and reports are also a symptom of the country increasingly turning in on itself.

Why is China turning its back on the world? The immediate reason is Covid. China’s border has been virtually sealed for nearly two years, and there is little sign of it re-opening any time soon. Foreign visitors are largely banned, and most people in China have not been allowed to travel overseas. Xi has not left the country since a visit to Myanmar in January 2020. China has maintained a ‘zero tolerance’ approach to Covid since the start of the pandemic. Local outbreaks are tackled with severe lockdowns which are enforced by claustrophobic surveillance of movement and contacts. Lanzhou, a city of four million people, was locked down in October after six cases were detected. In the same month, more than 30,000 visitors were locked inside Shanghai’s Disneyland theme park after a single customer tested positive. They were all required to undergo tests before being allowed to leave.

‘Zero tolerance’ is now as much about politics as it is about health. Xi has become a prisoner of his own triumphalist rhetoric. The CCP has presented the containment of Covid-19 as evidence of the superiority of the China’s authoritarian political system. At the same time, China’s homegrown vaccines (where data is available) have a lower efficacy than their western counterparts. Xi doesn’t dare to let his guard down.

Foreigners are leaving China in droves. Over the past decade, the number of expatriates in Shanghai, China’s financial centre, fell by 20 per cent to around 163,000. The decline in Beijing was even steeper, falling by 40 per cent to about 63,000, according to Ker Gibbs, the president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai. In Hong Kong, where the city’s ‘one country, two systems’ formula was shredded by China’s security law last summer, an American Chamber of Commerce survey in May found that 42 per cent of the expats questioned were considering leaving.

While Covid-19 has accelerated the exodus, the broader reason for it is that China is becoming a less hospitable place for western business and foreigners in general. Some of this is down to the business environment — tax policies have become harsher, and the party is now armed with new laws which empower it to take out through the front door what it used to steal from the back — but it is also a result of a growing and narrow-minded nationalism that is hostile to foreign ideas.

China’s inward turn suits Xi’s immediate purposes. National self-reliance, particularly in technology, has become a party mantra, as has a desire to inoculate the population against dangerous foreign influences. The months ahead are also crucial to his consolidation of absolute power in China. The groundwork has been laid. A 12,000-word homage, published by the state news agency Xinhua ahead of the CCP’s central committee meeting last month, described Xi as ‘a man of determination and action, a man of profound thoughts and feelings, a man who inherited a legacy but dares to innovate and a man who has forward-looking vision and is committed to working tirelessly’.

The party gathering passed a resolution on history, a power grab that elevated Xi’s status to the level of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. A communiqué stated that ‘establishing comrade Xi Jinping’s position as the core of the central committee as well as of the whole party… was of decisive significance in advancing toward the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’. A party congress to be held in late 2022 will effectively allow him to remain in power for life.

During the two years that Xi has sealed China off from the world, the world has grown far more wary of China. There are multiple reasons for this, ranging from repression in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, to Beijing’s initial cover-up of Covid-19, to the economic bullying of Australia. A Pew Research Center survey found that unfavourable views of China are at record highs in most advanced countries since polling on this topic began more than a decade ago.

The West’s increasingly cautious view of China has in turn fuelled CCP paranoia. This does not bode well for attempts by Joe Biden to engage Xi in talks on nuclear weapons, following China’s testing of a hypersonic weapon and assessments that China is rapidly expanding its nuclear arsenal. Beijing has consistently rejected conversations about arms control. There is no nuclear hotline, and none of the protocols or depth of mutual knowledge that existed during the last Cold War.

Xi is now engaged in a significant reversal of ‘reform and opening up’, the approach that has mostly characterised Chinese policy to the world since Deng Xiaoping. The barriers erected to keep out Covid are the embodiment of a wider and growing mentality. China is retreating into a dangerous bunker of Xi’s making.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in