Geoffrey Blainey’s famous reference to ‘the tyranny of distance’ — the title of his 1966 history — may resonate less today than it did with previous generations of Australians. In a world of increasingly rapid international transport and almost instantaneous communications, the sense of isolation has markedly decreased in recent decades, although Covid travel restrictions resurrected an historical consciousness of remoteness.

Reflecting on the significant changes wrought by the second world war, Blainey wrote of the Indo-Pacific neighbourhood: ‘The new Asian nations had more vigorous nationalism and far more acute social and economic problems than the average European nation. Australia, after existing in secure isolation for more than a century, had drifted into a new orbit of dangers and uncertainties.’ The war proved that isolation exposed vulnerabilities. The Japanese naval commander Admiral Yamamoto’s plans to cut off Australia’s communications and supplies from the US by establishing control of the South Pacific were never fully realised, but his forces inflicted severe damage, sinking the American fleet at Pearl Harbour and establishing a perimeter from PNG across the ocean. He was driven back in the Battle of the Coral Sea. If his plans to control the Pacific Islands had succeeded, Australia would have been left in an even more dangerous predicament. The Japanese forces were driven from the region by the allies, but the ‘new orbit of dangers and uncertainties’, of which Blainey wrote has been our reality ever since: conflicts in Korea, Malaya, Vietnam and Timor Leste; unrest in Myanmar, Bougainville, Fiji, the Solomon Islands, West Papua, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Remarkably, Australia put aside old enmities towards the Japanese people, and established a strong trading relationship within 15 years of the war. While animosity lingered for those who had suffered at the hands of their former enemy, Australia was blessed by post-war governments which strove to meet the challenges of a new reality. Our growing personal engagement with Asia, something that Blainey was unable to observe in the early 1960s, was built on migration and enhanced by tourism. Despite this, the geographic reality of the Pacific remains as it was in the 1940s: Australia is an isolated continent, significantly dependent on a peaceful, harmonious region and critical maritime trade routes. Any substantial interference to that stability is a threat to our security and prosperity.

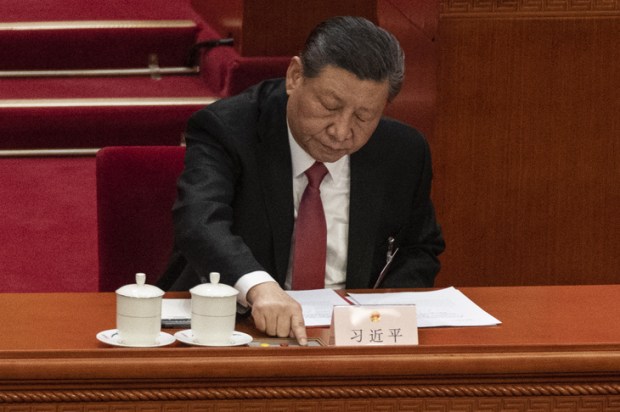

Recent events suggest that stability is being challenged. While ongoing terrorism cannot be underestimated, and ethnic conflicts will continue to simmer in various places, the major threat is from China, which has been pushing its influence in Australia’s Pacific neighbourhood — Tonga, Samoa, Fiji, the Solomons, Kiribati and PNG.

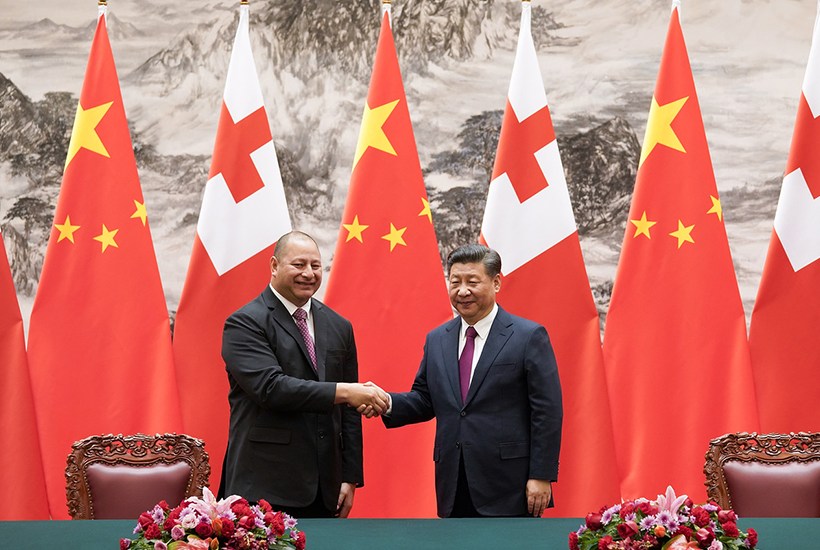

Tonga fell under the influence of China when taking loans to rebuild the capital Nuku’alofa, after riots destroyed much of it in November 2006. Since then, the Chinese Communist Party has feted the islanders, offering many sweeteners to the locals, including training its Olympic athletes. The kingdom is one of the largest Chinese debtors in the region — some two-thirds of the nation’s debt is owed to China. It had to ask for a restructure of the loans in 2020 and stands exposed to making further concessions to the CCP.

By ‘assisting’ Pacific nations to rebuild after regular natural disasters, China has infiltrated the region. In December, the envoys to China from Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, the Federated States of Micronesia, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu attended the launching ceremony of the China-Pacific Island Countries Reserve of Emergency Supplies program in Guangzhou. Chinese ‘assistance’ to Tonga following the recent volcano eruption compounds the nation’s obligation.

Some nations, having observed Tonga’s predicament, have grown wary. The new Prime Minister of Samoa cancelled a $100 million Chinese-financed project to expand the island’s seaport after defeating the Beijing-aligned former government.

Concerns have also been raised in Fiji, which faces an election at the end of 2022.The current Prime Minister, Frank Bainimarama, was courted by China following his military coup in 2006, and offered funding through the China-Pacific Island Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forum. An incident in October 2021, in which Chinese diplomats gate-crashed a Taiwanese National Day reception in Suva, intimidating guests and bashing a Taiwanese official, was covered up by the Fijian government. The exposure of the incident, which expands the meaning of ‘wolf warrior’, has provided fuel for opposition leader Sitiveni Rabuka’s campaign against over-reliance on Beijing.

A week ago, the US Indo-Pacific coordinator, Kurt Campbell, said America had not done enough to assist the region. ‘If you look and if you ask me, where are the places where we are most likely to see certain kinds of strategic surprise — basing or certain kinds of agreements or arrangements — it may well be in the Pacific,’ he said, in what many understood as a reference to Chinese plans to upgrade an airstrip on one of the islands of Kiribati.

Closer to Australia, pressures in the Solomon Islands have been exacerbated by tensions arising from the current government’s ties with China. Ongoing civil unrest in Honiara arises from both economic issues and the decision of the government of Prime Minister Manesseh Sogavare to end diplomatic ties with Taiwan in favour of China in 2019. Both AFP and ADF personnel were deployed to the Solomons in November following civil unrest in the capital. Payments from a Chinese fund to MPs were used to secure votes for the embattled Prime Minister. More recently, Chinese police have been invited to train members of the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force.

The CCP has also wooed PNG, proposing a major city, port infrastructure and a fisheries hub on Daru Island in the Torres Strait, north of Cape York. The scheme did not eventuate, but other proposals have been floated occasionally.

China is entitled to pursue investment opportunities globally, but its pattern of behaviour suggests mixed motives. Ports in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Africa involve not only economic investments, but strategic opportunities. China has invested more than $1.3 trillion in 42 Commonwealth states alone since 2005. The existence of ‘toxic’ clauses in contracts for Belt and Road Initiative projects, such as occurred with Uganda’s Entebbe airport, illustrate the predatory nature of these agreements. Given the convergence of the economic and military interests of the CCP, an otherwise benign investment always carries longer-term dangers.

Australia has responded with the South Pacific step-up – a necessary programme given the new strategic competition in our backyard. The funding of Digicel to provide a communications network in the South Pacific is both sensible and strategic. The recent announcement that Australia will fund major upgrades for seven PNG ports is also significant. But Australia and New Zealand must do more. Otherwise, Admiral Yamamoto’s plan to control the sea lanes of the Pacific will become a reality under the domination of the repressive Chinese regime.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in