A spectre is haunting the former Soviet Union — the spectre of people power. Every time it appears, Vladimir Putin leads an unholy alliance of all the reactionary autocrats of the former Soviet space to try to exorcise it. Last week, Putin sent 3,000 Russian paratroopers to Kazakhstan at the request of its president to crush a sudden revolution that left at least 160 protestors and 12 security officers dead.

For the time being, it looks like Putin’s timely intervention — as well as an internet shutdown that paralysed protestors’ ability to coordinate — has successfully quelled the flames. Kazakhstan 2022 has not joined the list of ‘colour revolutions’ that toppled the corrupt, mostly pro-Russian governments in Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004, Kyrgyzstan in 2010, Ukraine (again) in 2014, Armenia in 2018 and Kyrgyzstan (again) in 2020. A combination of swift and ruthless violence against protestors, mass arrests and military help from Moscow has beaten the genie of revolution back into its bottle and saved the regime — just as it did in 2020 when the Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko succeeded in thrashing his opponents into submission.

Nonetheless, the explosion of violence in Kazakhstan must have Putin worried — not only for the present, but for the future of Russia if and when he ever hands over power. Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan’s founding president, resigned in 2019 after 28 years. His successor Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, handpicked for his loyalty to the Nazarbayev clan and willingness to obey his old boss, lost control in little more than two. Protestors’ anger was channelled as much at Nazarbayev as at his sock-puppet heir. A Nazarbayev statue in the city of Taldykorgan was pulled down in scenes reminiscent of the fall of Saddam Hussein. And the sock-puppet’s reaction should give Putin food for thought too. In a vain attempt to quell the protests, Tokayev sacked Nazarbayev from his post as head of Kazakhstan’s Security Council, from where he had exercised behind-the-scenes control — a move that managed to be both grossly disloyal and ineffective at the same time.

The key problem for Putin is that modern Kazakhstan’s economy and politics are disturbingly similar to Russia’s. Georgia, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia were all chaotically democratic before their various people-power revolutions. But Kazakhstan is an authoritarian petro-state run by a small clique of billionaire bureaucrats with ties to the Soviet KGB. Like Putin’s inner circle, Nazarbayev’s family and cronies have stashed billions abroad. The Sunday Telegraph recently revealed that the former president’s daughter Aliya Nazarbayeva spent £18 million on a luxury jet, £8.75 million on a Highgate mansion and £14 million on a property in Dubai — part of some £220 million moved out of Kazakhstan in 2006. Nazarbayev’s son-in-law paid £15 million for Sunninghill Park, Prince Andrew’s former marital home, in 2007.

And just like in Russia, Kazakhstan’s police have been relentlessly cracking down on the opposition for decades. The media is firmly in the hands of the state and its allies. Elections are closely controlled. Yet the thunder clapped, as the Russians say, apparently out of a clear blue sky. Protests over rising petrol prices quickly escalated into car-burning riots across the country — shades of France’s gilets jaunes — fuelled by widespread resentment at corruption, inflation, and the wholesale plundering of their country by the elites. Most worryingly of all for Putin, the revolution materialised apparently without coordination, leadership or warning.

Kremlin propagandists were quick to identify the meddling hand of the West. The unrest was a flanking attack organised by the West to distract Russia from its attempts to bring Ukraine into Nato, agreed the pundits on Rossiya 1’s 60 Minut political talk show. The latest move in the US state department’s ongoing campaign to take over the former Soviet space by fomenting unrest via Trojan-horse human rights NGOs has been thwarted by Putin’s swift intervention, was the verdict of NTV’s Mesto Vstrechi.

Equating opposition and protest with foreign meddling has been a central part of Putin’s ideology for almost as long as he has been in power. Kremlin strategists firmly believe that the colour revolutions in the former Soviet Union — as well as successful popular uprisings in Tunisia, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon, Libya and Yemen — are the result of a ‘hybrid war’ policy by the West to remove inconvenient foreign regimes from power without direct military interventions.

Indeed, every step that the Kremlin has taken to shut down Russia’s domestic opposition and strengthen the state’s defences against subversion can be linked directly to various people-power revolutions. After the Rose and Orange revolutions in Tbilisi and Kiev in 2003-04, Putin ordered his ideological chief Vladislav Surkov to formulate the new national creed of ‘sovereign democracy’ and form Nashi, a nationwide patriotic youth group designed to mobilise its members against pro-democracy protests at home. In the wake of the 2014 Maidan revolution in Kiev, Putin launched a crackdown on the remaining vestiges of free press at home and stepped up policing of online dissent, arresting bloggers and social media users for anti-regime posts. He also launched Russia’s own counter-attack — a hybrid war against the US fought by proxy by trolls, hackers and social media manipulation targeting Hillary Clinton’s 2016 election campaign — and formed the Russian National Guard, a 340,000 strong security force under his personal control designed precisely to stem street protests.

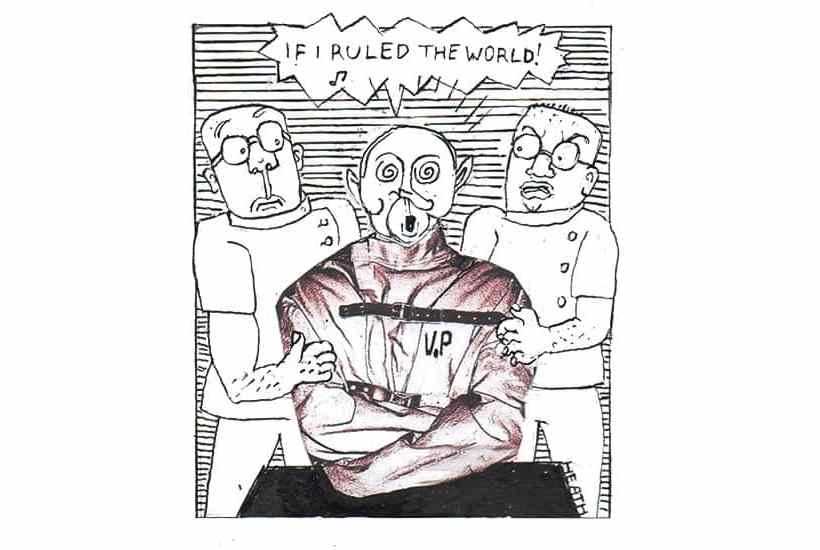

Putin’s predecessor Tsar Nicholas I reacted to the stalking spectre of revolution by styling himself the ‘gendarme of Europe’ dedicated to preserving autocracy. Similarly, Putin has made Russia the arsenal of anti-democracy by offering military support to any member of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), a post-Soviet military alliance led by Russia. With Moscow’s encouragement, CSTO member states Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan also sent troop contingents to Kazakhstan after an appeal by Tokayev for help against ‘external attack’ from ‘bands of terrorists’.

Putin’s paratroops are in Kazakhstan at the invitation of that country’s government. But cross-border troop movements on the pretext of quelling unrest are an uncomfortable reminder of the events of 2014, when Russian troops in uniforms without insignia were deployed in Crimea, allegedly to preserve the Russian-speaking population from an ongoing ‘genocide’ perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists. The genocide was nonexistent, yet the troops remained to annexe the whole territory to Russia. ‘One lesson of recent history is that once Russians are in your house, it’s sometimes very difficult to get them to leave,’ the US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said last week of Putin’s intervention — a remark that Russia’s foreign ministry called ‘typically offensive’. And in the context of Kazakhstan, Blinken’s jibe is also nonsensical. Though Russians form nearly 20 per cent of Kazakhstan’s population, there is no serious suggestion that Putin intends to carve off any slices of its close ally’s territory.

But the Kazakh intervention does make for a tense start to a week of negotiations between Russia and the US on the future of Nato deployments in eastern Europe and Ukraine. Putin has been massing more than 100,000 troops on Ukraine’s border since late October, and before Christmas demanded that Nato give ‘legal guarantees’ that it would stop military assistance to Ukraine or deployment of offensive weapons in frontline Nato states in eastern Europe.

For understandable historical reasons, the leaders of Ukraine, Georgia, Poland, Lithuania and many former territories of the Russian and Soviet empires firmly believe that Putin’s intention is to recreate the USSR by steadily taking back chunks of territory from his neighbours. Putin ‘shows a determination to carry out the scenario of rebuilding the Russian empire’, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki told his parliament in November. ‘A scenario that we, all Poles, have to forcefully oppose.’

Putin has always insisted that all he wants to do is defend Russia from western aggression. In a press conference last month he accused the West of ‘coming with its missiles to our doorstep’ — and repeated his mantra that all Russia wants is an end to Nato’s commitment to Ukraine’s eventual membership. Is that just a cynical bluff to cover his imperial ambitions, or does Putin truly believe that he is just defending his country?

The answer lies in Putin’s personal history, and the worldview it created. On the night of 5 December 1989, Putin faced down a small group of protestors who had appeared at the Dresden villa that housed the local KGB headquarters — part of a much larger crowd who earlier that day had stormed and sacked the local Stasi office. Two years later he stood behind his then-boss, St Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak, as hundreds of thousands of people turned out to protest against an August 1991 coup by communist hardliners — Russia’s own people-power revolution. Putin knows from direct personal experience how crowds can change history — and how quickly a state’s apparently formidable security force can melt away.

And he also knows from his own later political career how easily crowds and populations can be manipulated. At the beginning of 1996, Boris Yeltsin’s approval rating stood at just 9 per cent. Yet Yeltsin won presidential elections in June that year after a sustained campaign of propaganda mounted by the media, whose still-independent oligarch owners remained bitterly divided against each other but united in their opposition to the resurgent communists. Putin, on coming to power in 2000, immediately brought Russia’s television under Kremlin control, and used and perfected the techniques of manipulation to cement his own popularity. By 2003 he was already trying to export the same ‘political technologies’ of media messaging and vote manipulation to influence elections in neighbouring Ukraine in an (ultimately unsuccessful) attempt to get a pro-Moscow candidate into power.

Yeltsin stayed in power through manipulation of popular opinion via the media — and that propaganda machine has remained the basis of Putin’s power for two decades. No wonder, then, that Putin has little respect for democracy. Or that he has difficulty in conceiving that Ukrainians who fought and died on the barricades of Kiev’s Maidan could have done so from personal convictions or a belief in freedom. As a lifelong KGB officer surrounded by men of a similar background, Putin is a natural conspiracy theorist. His training instilled a deep belief that public politics are the result of machinations by secret services. As he wrote in a long essay on Ukraine last year, Kiev’s attempts to assert its sovereignty are part of a western-imposed ‘anti-Russia project’.

Putin may be ill-informed. He may be paranoid. But by his own logic both his intervention in Kazakhstan and his heavy-metal diplomacy on Ukraine’s border are defensive acts intended to fend off a western campaign to subvert and depose him and his neighbours. That threat is, in reality, nonexistent. But as the West engages in crucial diplomacy in Geneva with Russian officials on the future of Nato, it’s important to remember that Putin’s actions are driven more by nightmares of revolution than dreams of empire.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in