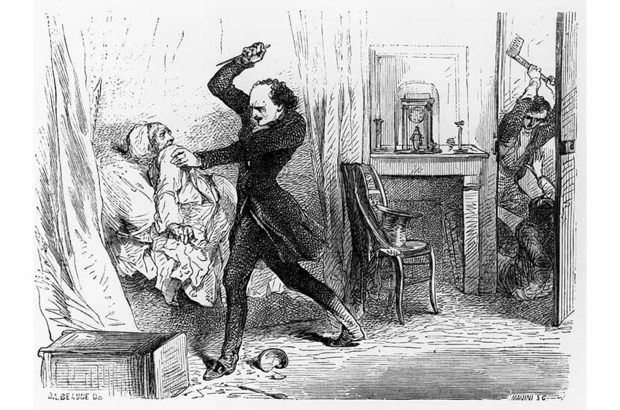

In January 1780 the news reached London that Captain Cook had been killed and eaten in Hawaii. The story of his death was met with morbid fascination by the general public, inspiring paintings, poems and even a ballet. This ballet was so violent that one of the dancers accidentally stabbed another during the scene of the attack, yet it was also a fantastic success, touring the theatres of Europe and America. Soon aristocratic women were wearing dresses modelled on the natives who killed Cook, and interest in the explorer’s death continued into the 19th century, until one wit noted that every museum in the world contained a copy of the club that killed him. So, who was it that really deified Cook: the Hawaiians who murdered him or the Europeans who made a martyr of his memory?

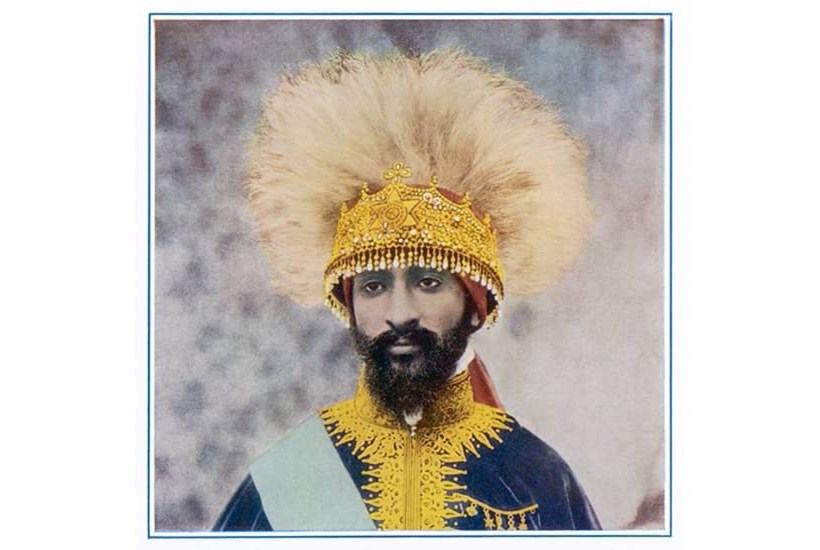

Anna Della Subin’s Accidental Gods is filled with soldiers and sailors, rulers and royals, who found themselves worshipped in their own lifetimes. Some of these are well known, such as the Emperor Haile Selassie, appointed by the Rastafari religion as its saviour; or Prince Philip, anointed as their messiah by the Melanesian islanders in Vanuatu. Other cults are more obscure, such as the four different ones that emerged around the figure of General Stanley MacArthur — in Panama and Korea, New Guinea and Japan — or the more recent religion devoted to Donald Trump, which boasts just a single member. Taken together, they offer a fascinating tour through the endless diversity of the divine.

The book is divided into three parts. The first looks at a scattering of 20th-century gods; the second focuses largely on India and the age of empire; the third on the Americas and the age of exploration. Each chapter takes a new deity as its subject, while drawing together a vast range of sources — the high and the low, the sacred and the profane — to create beautiful passages of rhythmical prose. In the process, we encounter a remarkable range of beliefs, from the spells of Aleister Crowley to the prophecies of Annie Besant, via phrenology, demonology and Robert Baden- Powell’s Scouting for Boys.

Deification was common in antiquity, with cults surrounding emperors and celebrated generals; but Subin focuses on the modern era, when traditional societies confronted the wealth, technology and power of the western world and created new gods:

Though the idea that a man could become deified may appear an arcane theological puzzle, a dream jettisoned from an enchanted past with the accident that was the alleged dawn of the modern age, the flood of sanctifications began to rise.

There are several extraordinary members of this modern pantheon, but it’s a mistake to think that they shared some exceptional quality which marked them out as worthy of godhood. Instead, Subin turns her attention from the worshipped to the worshippers, asking what complicated needs these figures filled for their devotees. In doing so, she untangles many of the assumptions shared by the colonisers, missionaries and scholars who first recorded these cults, and whose views on indigenous religions were often lazy or misguided. According to Subin, because most of these scholars were raised in a Christian context, the words they translated as god and the practices they described as religion became ‘vessels of Europeans’ own monotheism’.

Though the book is scrupulous in attending to the many varieties of belief, concepts such as ‘empire’ and ‘western’ are used in an undifferentiated fashion. However, the colonial experience ranged from trading partnerships to military suppression. Such distinctions matter, because Subin argues that many of these men were made gods in response to the imperial presence, as a way of reclaiming or even taming their power. But this implies that the experience of living under imperial rule was everywhere the same, reducing rather than enriching the complex motives behind belief.

Monotheism makes a stranger of god, a vast and distant deity who withdrew from human affairs long ago. By contrast, there’s something exhilarating about the proximity of these living gods, who eat and sleep and walk the streets, but might, just might, be touched with the divine. When touring Morocco with Nathaniel Tarn — an anthropologist who was deified while conducting research in the Guatemalan highlands — Subin writes: ‘Rather than some place unlocatable, unfathomably high above us, perhaps transcendence is all around us, and so the sacred stays within reach for us to grasp when we need it.’

The final pages of the book take this further, suggesting that true equality will only be achieved when people other than white men can be celebrated as divine. But you don’t need to end up bludgeoned and barbequed like Captain Cook to conclude that being worshipped is nothing to be wished for.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in