Never Not Once has a cold and forbidding title but it starts as an amusing tale set in an LA apartment. We meet Allison, a happily married lesbian, whose grown-up daughter, Eleanor, arrives with a hunky new boyfriend to show off. This set-up has the makings of a flatshare sitcom. You combine a straight younger couple with an older pair of lesbians and you throw in the mother/daughter relationship for extra instability. It could be a laugh. But a new wrinkle appears. Eleanor learns that she was conceived during a one-night stand and she decides to track down her absentee father. But he’s extremely reluctant to discuss what happened that evening. Too much booze, he shrugs, and the major details escape him. Flora disagrees with this version. Eleanor’s father raped her, she claims. Wow. This frothy comedy has turned into a heavyweight examination of consent and coercion. It develops into a poignant knife-edge drama which delivers an excellent ending. The characters discover the nobility of forgiveness and the harmful futility of vengeance.

It’s unusual to find a play that could do with opening itself up a bit, breathing more, taking its time, and exploring the characters further. (The tame boyfriend is a dud who could benefit from extra investigation.) The playwright, Carey Crim, is a gifted comedian who may have suppressed her natural humour in the hope of pleasing a handful of mirthless and puritanical commentators. If so, that mistake should be corrected.

An Evening Without Kate Bush is a song medley delivered by a lifelong fan, Sarah-Louise Young, who first imitated her idol at school in the 1990s. Kate Bush is now her vocation and she takes the show to festivals and small venues around the country. The hits are interspersed with biographical details. Bush was just 13 when she wrote ‘The Man with the Child in His Eyes’. Her breakthrough song, ‘Wuthering Heights’, was released despite the scepticism of record executives who felt it was too weird to prosper. They were over-ruled by Bush, and she became the first British female artist to write and sing a number one hit. Young admits that Bush’s work is ‘easy to parody but hard to understand’, and she delivers a set of satirical tips for anyone wishing to mock Bush’s wacky dance style. But her over-riding attitude is one of depthless adoration. She can sing ‘Babooshka’ in perfect Russian and she explains the correct pronunciation of the key word: ‘bah-boosh-kah’. The stress falls on the first syllable and it rhymes with ‘pa’ and not with ‘cab’.

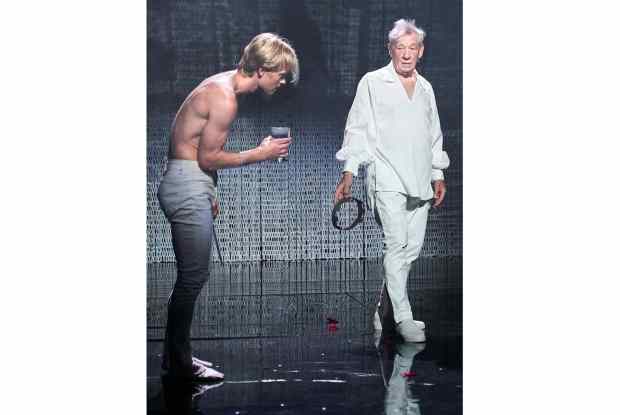

Hamlet at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse is a strange mixture of modern and period costumes. Most of the characters in Elsinore wear fancy-dress outfits with stiff ruffs and long flouncy skirts. They look like playing cards. Other characters are in contemporary street stylings. It’s not clear what this confusion is supposed to explain. And the mismatched clothes make the drama fundamentally unserious. It’s impossible to believe that these giggling clowns are really a crew of medieval gangsters engaged in a power grab that involves adultery, betrayal and assassination. It all looks a bit Blackadder. And any suggestion of religious mystery or menace is lacking.

There are other oddities, too. Why do some of the actors deliver famous speeches as if they hadn’t a clue what they meant? Is there a reason for Ophelia’s swaggering elder brother Laertes to be played by a willowy blonde? And how come Hamlet’s pal Horatio looks at least 30 years older than his closest friend? Anyone watching the play for the first time will find much of this mystifying.

But they’ll relish George Fouracres’s turn in the lead role. He appears as a Goth, clad in black from top to toe, and sporting a sturdy pair of DMs. And he delivers the verse, like Ozzy Osborne, in a rich Brummie accent that may not be too far from Shakespeare’s own patterns of speech. His amusing, joshing style pays a few dividends but it can’t possibly capture the full range of the part. And some of the props defeat him. The decision to make Hamlet fight Laertes using a pair of poison-tipped cricket stumps is an innovation that’s unlikely to be copied by future productions. Fouracres’s best moments come during his verbal jousts with Polonius (John Lightbody), who acts as his straight man. Lightbody brings gravitas and poise to the part, and although he never plays it for laughs he gets a great reaction all the same. Whenever he appears he gives the scene an air of purpose, weight and authenticity. And suddenly this feels like Shakespeare. When he departs, the effervescent dippiness returns. To say that Polonius is the best thing on stage is an unusual comment to make about Hamlet. Don’t take it as a recommendation.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in