It is a peculiarity of how France has responded to the Covid pandemic that the unvaccinated, or those who have had only two jabs, are regarded as a greater threat to national security than Islamic extremists.

The Covid passport, which came into effect last week, won overwhelming backing in parliament and in the senate, despite the reservations expressed by the Council of State in December. They said the passport would restrict the unvaccinated’s ‘liberty to come and go’.

Six years ago the Council articulated similar concerns when the then-president, François Hollande, proposed a law that would strip dual nationals of their French citizenship for those convicted of terrorist offences. France was reeling from the Isis-inspired attack on Paris that left 130 dead, but the left still opposed a law they regarded as antithetical to the Republic’s cherished principles of liberté, égalité, and fraternité.

The Guardian reported that human rights organisations were opposed to the move because it ‘would be unconstitutional in creating two different classes of French citizenship, in contravention of the constitution’s founding principle of equality.’

That was forcefully expressed by the left-wing senator Marie-Noëlle Lienemann, who warned of an iniquitous ‘breach in the constitutional principle of equality between citizens.’ She added that ‘what is applied today to terrorists may one day be applied to anyone who is seen as a threat to French values.’

So strongly did the Justice Minister Christiane Taubira feel about the proposed bill she resigned from the government in January 2016, and a few weeks later Hollande abandoned the proposal.

But a few months later there was another outrage, the murder of a policeman and his wife in front of their infant son by a man pledging allegiance to the Islamic State. The killer had become radicalised in prison and for many years had been on an intelligence watch-list.

There was fury on the right and Eric Ciotti, a Republican MP, demanded the establishment of retention centres for the estimated 1,000 extremists under surveillance.

The government had in fact sought advice from the Council of State after the Bataclan attacks about the constitutional legitimacy of some form of retention centre for those extremists who were considered a potential threat but had committed no crime. The Council of State replied that such a measure would contravene the French constitution as well as European Convention of Human Rights.

The Council also examined the possibility of house arrest, but advised that any such restriction must leave the individual a ‘freedom of movement compatible with a normal family and professional life.’ Instead the Prime Minister, Manuel Valls, appealed to the country to show ‘solidarity and collective calm’ and urged people ‘to learn to live with terrorism’.

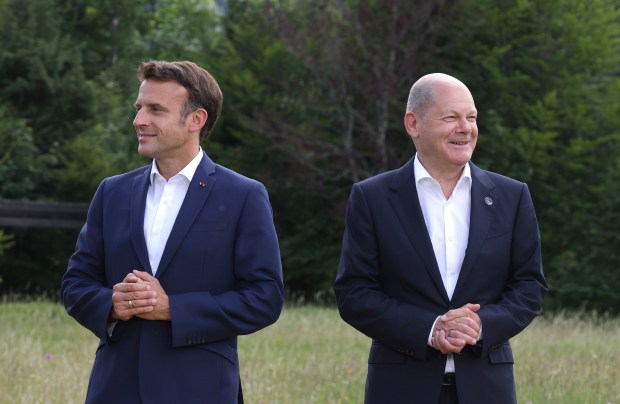

So the French kept calm and carried on, until another murderous Islamist attack, this one in Trèbes in southern France in 2018. Emmanuel Macron was now the president but there was no change in position on the question of depriving extremists of their liberty. ‘The law does not authorise the locking up of people for suspicious behaviour without any tangible evidence,’ said a statement on the official website of En Marche!, Macron’s party. ‘Internment would be a violation of the basis of our law in France.’

Covid has shattered this commitment to individual freedom. For two months in the spring of 2020, Macron confined the French to their homes, allowing them out only to buy groceries or to stretch their legs for an hour within one kilometre of their residence. Anyone who did venture onto the streets had to have about their person a completed form giving details of their name, address and reason for leaving their house.

There was another similar lockdown in the autumn of 2020 and then a night-time curfew in the winter. This winter Macron proscribed his citizens from travelling to Great Britain. How is it possible that an estimated 2,000 French nationals were able to travel overseas to join the Islamic State but no one was allowed to go to the UK to spend Christmas with their families and friends?

The consequences of the institutional indifference of the French State to Islamic extremism was laid bare in a TV documentary aired last week. Viewers saw boys and girls segregated in classrooms, men and women eating in separate cubicles in restaurants and dolls without faces sold in Islamic shops to conform to Salafist teachings. The presenter of the documentary is now under police protection after receiving death threats.

The political class have expressed their indignation but this parallel society within the Republic was first highlighted in 2002 in a book entitled The Lost Territories. That it has flourished is because successive governments have been afraid to interfere in case they were accused of Islamophobia.

Macron is no different. The unvaccinated are an easy target for a president wishing to appear tough and uncompromising against an internal enemy. ‘When my freedoms threaten those of others, I become someone irresponsible, someone irresponsible is not a citizen,’ was how Macron justified the Covid passport last month. He continued: ‘You will no longer be able to go to the restaurant, you will no longer be able to go for a coffee, you will no longer be able to go to the theatre, you will no longer be able to go to the cinema.’

Thousands of nurses, care workers and firefighters have been indefinitely suspended because they refused to take the vaccine; last week a prominent doctor proposed that the unvaccinated should no longer be entitled to free health care.

One of the handful of left-wing senators who voted against the passport was Marie-Noëlle Lienemann; six years ago she railed against the idea of stripping Islamists of their dual citizenship because, as she said at the time, it was a breach of the ‘principle of equality between citizens.’

But whereas in 2016 Lienemann held a majority opinion, today she is in the minority. Her peers regard the unvaccinated as a clear and present danger to the Republic. There is no talk in 2022 of showing ‘solidarity and collective calm’, of learning to live with Covid as they did with Islamic terrorism. Instead there is fear and hysteria and exclusion, and a betrayal of the constitution’s founding principle of equality.

What a peculiar country France has become when its politicians strive to preserve the freedom of Jihadists and vote to restrict the liberty of the unvaccinated.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in