Two markers: ‘Cottages at Auvers-sur-Oise’ (c.1873) is a sweet especial rural scene of faintly slovenly thatched cottages with, at its centre, an outside privy, its door modestly shut. A discreet little detail. Second, early in the exhibition, Corot’s ‘Duck-Pond’ (1855–60), an indicator of the tradition to which Pissarro belongs — a world of unconsidered trifles, granted a quiet importance. Linda Whiteley’s excellent, informative catalogue essay quotes Pissarro on Corot: ‘Happy are those who see beauty in modest places where others see nothing. Everything is beautiful, the whole secret lies in knowing how to interpret.’ He is writing this credo to his son Lucien in 1893. Later, Cézanne described Pissarro as ‘humble and colossal’.

As a painter, his orientation aligns with modernism’s turn towards the banal — Edward Thomas’s ‘Tall Nettles’, T.S. Eliot’s typist laying out her food in tins, Joyce’s Buck Mulligan slicing open a scone and plastering butter ‘across its smoking pith’. You could say this change of focus began with Jane Austen’s attention to pattens and parcels in Emma and is evident in Chekhov and Gogol’s inclusion of card games in their art. Think of Cézanne’s ‘The Card Players’ with their clay pipes. It’s a long way from Delacroix’s ‘The Death of Sardanapalus’ (1827) with its Cecil B. DeMille teeming welter of naked flesh, where everything is a headline. We are now in the world of small print, a world in which we most of us live — a world of bidding two no trumps at bridge.

So Pissarro is a convenient fit. He is a sympathetic figure. But how good is he? This exhibition, edited since Basel to fit the Ashmolean’s three travelling exhibition rooms, is keen to create context and includes work by Pissarro’s contemporaries — Cézanne, Seurat, Degas, Signac, Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin. On the whole, these painters simply outshine Pissarro. ‘Bouquet of Pink Peonies’ (1873) immediately reminds us of Manet, with his royal flush of perfect peonies, and in particular his ‘Peonies in a Vase’ (1864) at the Met in New York. The problem, it seems to me, is Pissarro’s slightly fuzzy version of impressionism, his uncertain execution, his approximism. The great impressionists are all lucid suggestion, touches, dabs, smears that take us accurately and swiftly to the heart of things. Their marks are perfect equivalents, exact approximations. A paradox which is not always true of Pissarro.

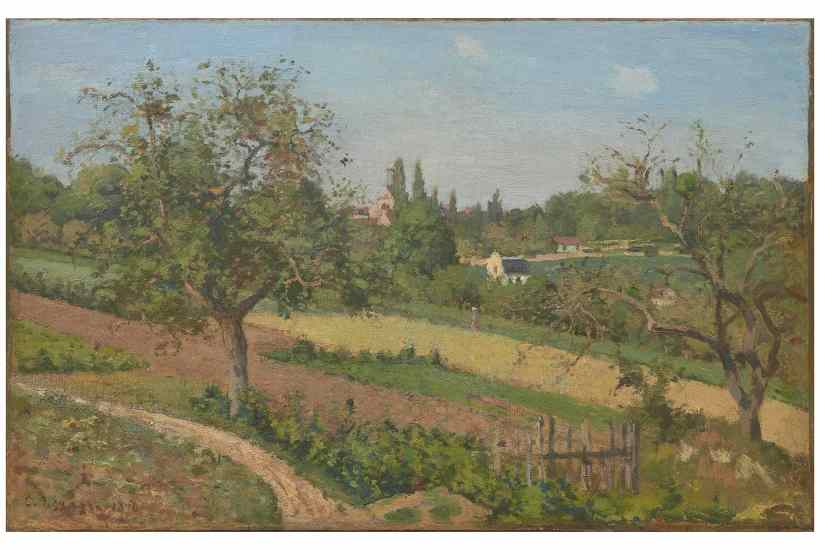

The ‘Countryside near Louveciennes’ (1870) is a case in point. It shows a tomato patch under an apple tree. There is a dead tree on the right — leafless, fruitless. A small fenced-off area might be for compost. At the bottom right, there are white patches and a possibly pink figure, who may be pegging out clothes. I can’t be sure. There is a lithograph, ‘Women Carrying Firewood’ (1896), in which brushwood is carried on shoulder panniers. One woman is also cradling an armful of sticks, her hands joined: her right arm is impossibly long. In the left background are cows. At first, I thought one cow was scratching its neck. Equally, it might be two cow heads, one slightly masking the other. Impossible to be certain. Looking as haggling.

The same thing is true of ‘Design for a Fan’ (1880). One of the best Pissarros, tempera on silk, it shows a harvesting scene. In the background, perfectly readable distanced activity. In the foreground, a frieze of figures, a couple facing away, others tedding the hay with forks and rakes. Everyone is wearing an apron. The colours are delicious and muted like the pastel shades in a packet of Refreshers. Light is indicated with forward-slash brushstrokes. In the left foreground, there is an optical puzzle. A man in a bowler hat appears to be sleeping. A wonderful detail, a brilliant detail — unless it isn’t.

Compare this with Paul Signac’s fan-piece ‘The Seine at Herblay, Morning Mist’ (1889). Best in show — by a mile — in a show which otherwise isn’t the greatest show on Earth. Not to be missed. On the protractor-precise semi-circle, the river’s vista going to its asymmetrical off-centre vanishing point. The roofs of the buildings on the left are little orange-gold lozenges. The trees on the right are a dying chord. The whole is held together by haze. And the blurred reflections in the water create a wonderful duet — no, a descant. A great deal of the silk appears to be empty at first — pure space, an empty mist — until you see a faint shared mottling, so subtle as to be almost invisible. The very texture of emptiness. In the catalogue reproduction, this painting is nothing. In actuality, it is a miracle of beauty.

Everything is perfect here. No haggling. Whereas that outside privy; the enormous ear of his young son Lucien, the size of a second row forward; a botched bonfire — in a way, imperfection is what Pissarro’s art embraces.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in