In his first book, How to Argue With a Racist, the geneticist Adam Rutherford set out a lucid account of how the basis for many widely held and apparently commonsensical ideas about race are pseudoscientific; and he lightly sketched, along the way, the historical context in which they arose and the ideological prejudices that nourished them. We might have some half-baked ideas about how evolution works — and have unthinkingly accepted racial categories invented by 18th-century imperialists — but, he assured us in perhaps the standout line of the book, the underlying genetics is ‘wickedly complicated’.

Control is a companion piece to that one. It again looks at the way in which ideological and political ideas co-opt science, or a half-baked understanding of it. These days, thanks to the Nazis, ‘eugenics’ is so dirty a word that it tends to blight anything it touches; and to that end it’s applied in newspaper scare stories to a whole range of interventions and ideas. Anything involving experimentation with embryos or stem cells will tend to ‘raise the shadow of eugenics’ — and give the reader a pleasant little shudder of horror.

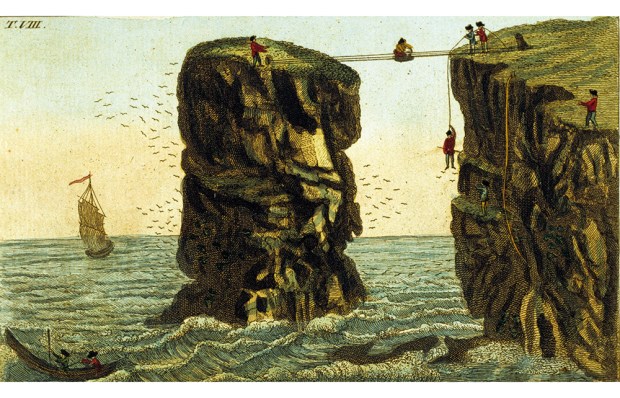

It was not always so. In the early part of the 20th century eugenics was seen by many eminent people across the political spectrum as a definite, even an obvious, good. Selective breeding — to be nudged along, perhaps, by discouraging those deemed to have undesirable characteristics from having babies — could surely increase the intelligence, health and prosperity of the mass of humanity. It was not a new idea: Plato’s Republic imagined an overclass of the bright and the beautiful making bright and beautiful babies; the Spartans, at least apocryphally, liked to drop weedy infants off cliffs. With the arrival of Mendelian and Darwinian ideas about heredity and the mechanisms of heredity, though, this old impulse gained a new respectability.

The founding father of the discipline in the UK was Francis Galton, who not only minted the term but invented twin studies and many of the statistical techniques that have since, ironically, been used to discredit his work. Rutherford doesn’t demonise the modern pioneers of eugenics, though he doesn’t mind calling them racists. Galton was a man of brilliance — but his Hereditary Genius was a ‘superlative showcasing of confirmation bias’. His disciple Karl Pearson’s ‘impact on the history of science was titanic’. Ronald Ayler Fisher ‘sits comfortably in the top tier of scientists of all time’. Yet all three tumbled down the rabbit hole of eugenics.

Definitions — particularly with a term so loaded — are going to be a problem. Can eugenics be usefully enough defined to be the subject of a book? Can a distinction be drawn between, say, the idea of euthanising the lame, the halt and the mentally disadvantaged for the good of the tribe — which most of us will now agree is not on — and what sound on the face of it like benign interventions? We screen in early pregnancy for Down Syndrome, for instance, and many parents use that to decide whether to carry the pregnancy to term. It’s at least theoretically possible in vitro to select for implantation an embryo with the lowest chance of having a hereditary illness. And as science advances, we’re talking about the possibility of editing the genome of an embryo immediately after conception to prevent it getting a hereditary disease. Gene-editing techniques gave us Covid vaccines. Are all those ‘eugenics’?

Rutherford draws a distinction, which I think just about holds, between ‘the alleviation of suffering in individuals, both parents and children […] rather than the overall improvement of the people as decreed by the state’. That is, if I understand him rightly: population-level interventions bad; individual interventions… well, at least more up for discussion.

The book’s great strength is explaining why. At population level, as he points out, decisions about what ‘improving’ a community might look like are not scientific but ideological ones. They imply a hierarchy of human value — and even where they do not end in Treblinka, they will tend to send you smartly in the direction of racism, ableism and classism.

Underpinning these theories, historically, was the fear that the diseased, the disabled, the undeserving poor or the racially other would ‘swamp’, contaminate or outbreed the bright and good. Rutherford links them — sketchily but not unconvincingly — to Victorian anxieties about a newly industrialised world with a growing and very visible underclass, swelled by immigration. Many, betraying their cultural biases, believed that Rome was done for by its lower orders outbreeding its rulers. Galton thought that the church fathers boobed by keeping their best theologians celibate.

The thought does occur that eugenicists have a version of the same problem as those Marxists who simultaneously claim to believe in the historical inevitability of capitalism’s collapse and agitate for armed revolution. If you really do believe the Nordic races have better and more vigorous bloodstock (or even that evolutionary pressures favour higher intelligence), why would you bother loading the dice? Wouldn’t you expect survival of the fittest to bring the master race out on top automatically?

In general, though, eugenicists have not been so relaxed: rather, they have imagined that just as we’ve managed to breed nice plump chickens for KFC, we can and should do something similar for Hom sap. They built plans for policy on a foundation of ideological nonsense, some of it well-intentioned and some of it very much less so. Garbage in, garbage out, as programmers say. Playground insults such as ‘imbecile’, ‘idiot’ and ‘moron’ were once held to be diagnostic categories — and all sorts of conditions, from mental retardation or psychological illness and other forms of disability to criminal recidivism, were conflated as signs of hereditary degeneration that warranted incarceration or sterilisation. The fat end of that wedge was ‘racial hygiene’ and the termination of what the Nazis called Lebensunwerten Lebens — ‘lives unworthy of living’.

But this book hasn’t settled for the fish-in-a-barrel project of making the case that something we’ve all learnt to think of as wicked is wicked. Rutherford is fair-minded enough, or at least scientifically minded enough, to be interested in trickier questions, such as: even if we decided that ‘positive eugenics’ was a good thing, would it actually work?

The answer is, so far, a resounding nope. It was a nope back then — when scientists proposed policies on the basis of over-confident guesses about how heredity worked that were just plain wrong. And it’s still a nope now. We know more about how genes shape us than ever before: and that has given us a much better sense of how little we know. The heritable components of general intelligence, say, or of susceptibility to schizophrenia, are associated with dozens or hundreds of genes we know about and many more we don’t. And their effects are plural and complexly interdependent. Here is where Rutherford, on home turf (‘When scientists play historian,’ he says wryly, ‘the risks are great’), is at his most fascinating.

Most popular ideas about heredity are fed by what he calls ‘monogenetic determinism’: the headline-friendly idea that ‘there’s a gene for X’: if there’s a ‘gene’ for blue eyes, then it seems to follow that you could deliberately select for blue eyes. But even examples like eye colour and hair colour — which GCSE students are taught in simplified form — aren’t even close to being so straight-forward. ‘It’s a fallacy in three dimensions,’ Rutherford writes:

Complex traits rarely have single genetic causes; they always involve the non-genetic environment, and genetics is probabilistic, not deterministic. This is a key reason why the eugenics project was always on precarious ground: the conditions under scrutiny, whether it was feeblemindedness or epilepsy or alcoholism, do have a genetic component to them — almost everything in human biology and psychology does — though they are never single genes; and those genetic causes are rarely if ever deterministic.

Rutherford argues that the tech-infatuated futurists who seem keenest on reviving a ‘nice’ version of eugenics for the 21st century (our own Toby Young gets a spanking, and Dominic Cummings a ticking off) just don’t understand the science well enough to really know what they’re talking about. At least for the foreseeable future, ‘designer babies’ are science fantasies; CRISPR gene-editing isn’t yet nearly the infallible DNA-typewriter of hype, and experiments that would get us further down the road to Gattaca are not only impractical and unreliable but hair-raisingly unethical in all sorts of ways.

Besides, it’s not practical, says Rutherford, to start fertilising great swathes of the general population in test tubes: the traditional method is easier and more fun. If you want to improve a population’s general intelligence, it’s cheaper, more effective and more humane — if, admittedly, more boring — to invest in education, nutrition, clean air and water, and to let evolution get on with its work. If we suddenly could eliminate Down’s or Huntingdon’s at a stroke, should we? Rutherford fence-sits on such questions, and you can’t blame him. But we’re nothing like there yet.

There are many involving arguments, historical surprises, detailed case studies and amiable jokes in this book, and you’ll finish it with renewed respect for, and interest in, what real scientists do. I’m afraid it defies a one-line summation because, well, it’s wickedly complicated.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in