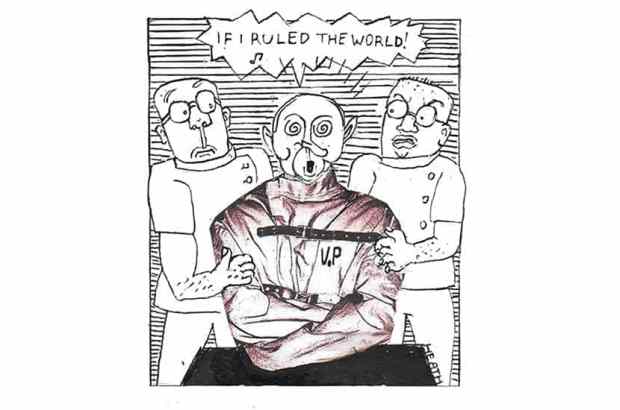

We are always cautioned against comparing a modern political event with those that led up to the second world war. One can see the risk of hyperbole and slander. But as Vladimir ‘Inky Poops’ Putin re-invades Ukraine, he will be making such comparisons himself. His long and bitter address on Monday showed his taste, common in tyrants, for historical disquisitions designed to turn grievance into aggression. He lambasted the foolishness of the Soviet leadership in the 1920s and 1930s which had laid ‘a mine to destroy state immunity to the disease of nationalism’. With the collapse of the Soviet Union from 1989, he went on, this had led to the rise in Kiev of ‘aggressive Russophobia and neo-Nazism’ and ‘a parasitic attitude acting at all times in an extremely brash manner’. Wicked oligarchs (yes, the President hates them, apparently) ‘embezzled the legacy inherited not only from the Soviet era, but also from the Russian empire’. Nato fastened on this, making Ukraine ‘a colony’ run by ‘puppets’. This makes it positively virtuous, in Putin’s view, for Russia now to intervene as ‘peacemakers’ in ‘independent’ Donetsk and Luhansk. Putin is displaying a righteous anger similar to Hitler’s as he invaded to ‘help’ Germans in the Sudetenland or Danzig. Like Hitler, Putin has long published his extreme versions of history, yet the democratic West paid little attention and neglected the international order. Hitler was emboldened by encountering western leaders. He said: ‘Our enemies are men below average, not men of action, not masters. They are little worms. I saw them at Munich.’ Putin may be making the same calculation, and he may be right. Hitler was righter militarily, than his generals, until Barbarossa. Putin, too, will have gained confidence from his previous conquests. ‘They won’t dare stop me,’ he must think, raking in the money from oil and gas. Today is his time. Tomorrow might not be.

A Polish friend writes: ‘I have just been watching Putin’s rather dark history lesson and his declaration of the absolute right of Russia to invade the “non-country” Ukraine… When signing the declarations with representatives from the rebel regions, Putin was seated 30 metres away from them. He continues to maintain his incredibly strict policy of essentially self-lockdown of these past two years — most people who meet him face to face have to isolate for weeks prior and are usually fogged with chemicals first. It was chilling to realise that Putin, although unafraid of all-out war and bloodshed for years to come, is still terrified of the mild cold which Britain’s 95-year-old monarch currently has and is happily untroubled by. I cannot think of a better indication that this is a man who has lost his ability to evaluate risk.’ Yes indeed, though one might add another possible reason for Putin literally keeping his distance: a man so experienced in the poisoning of others must be very conscious of the range of novichok, suddenly thrown.

On Tuesday night, my sister Charlotte was on her fifth day of the power cut caused by Storm Eunice. So was our mother across the fields, stuck upstairs because her stairlift cannot function. Charlotte’s only contact with the outside world is her landline, at the other end of quite a large house. It rang at 2.07 a.m. Fearing that it might be my mother’s emergency lifeline ringing, Charlotte struggled through the freezing dark to the phone. When she picked it up a recorded voice said: ‘We’d like to inform you that there has been an unplanned power cut in your postcode area. Not all properties have been affected by this power cut. If your property has been affected, we’d like to apologise for any inconvenience caused.’

In devoutly Brexiteer circles, the idea is circulating that Lord Frost should disclaim his peerage, win a seat in the House of Commons and then become prime minister. A tempting thought, perhaps, but Conservative MPs would never accept this. It would make a mockery of their long years of elected toil to be leadership candidates themselves. Besides, there is no provision in law for such a disclaimer. Since 2014, people have been allowed to resign from the House of Lords, but not to surrender their peerages. Only hereditaries can disclaim, and only at the moment of inheritance. You can see why the Frost option is not allowed. If it were, the Lords could become a cushy way of gaining political connections and experience which could then be ‘weaponised’ to get into the Lower House. In theory, however, it remains the case that you can be prime minister from the House of Lords. Perhaps Lord Frost should try for that: it would allow a lot more time for actual governing, rather than having to shout for hours from the green benches.

Perhaps I overreacted because I was preoccupied with the dramas of Storm Eunice, but when I read this weekend that the first of Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules of Writing is ‘Never open a book with weather’, I thought how silly rules of writing can be. If Leonard’s Rule 1 were enforced, out would go the first scene (and the name?) of The Tempest; same with Macbeth. You would have to jettison the first sentence of Nineteen Eighty-Four, ‘It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen’, or of Jane Eyre, ‘There was no possibility of taking a walk that day… the cold winter wind had brought with it clouds so sombre and rain so penetrating…’, or of Bleak House, ‘Implacable November weather’ (followed by the second paragraph, ‘Fog everywhere’). Weather is often the best way to open a novel or play, because it sets a scene and a mood and usually places human figures in its landscape. Without it, many more paragraphs would have to be expended explaining where we are, what time of year it is and what sort of people are depicted. Not for nothing are ‘It was a dark and stormy night…’ the only words of Edward Bulwer Lytton that anyone remembers.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in