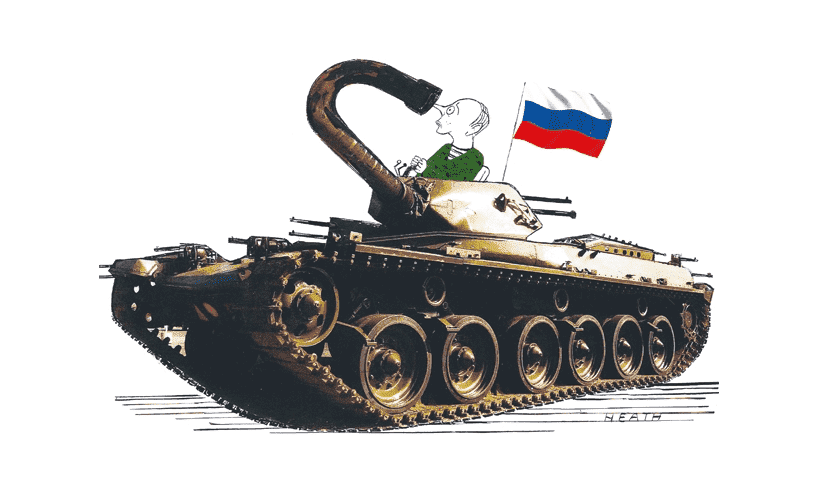

Russia will pay an enormous price if it invades Ukraine, whether it goes for the whole country or only the eastern region around Donbas. Vladimir Putin has already assembled well over 100,000 troops near Ukraine’s borders, moved in tanks, heavy artillery and aircraft, and brought in the medics and blood supplies needed to deal with casualties. Western governments have evacuated all but essential diplomatic personnel and told their citizens to get out now.

Still, no one knows what Putin has decided, or even if he has decided. Visits to Moscow by senior western politicians have yielded little information and no diplomatic solution. The message seems to be that Putin remains uninterested in a compromise.

Instead of trying to guess what Putin will do, let’s focus on the costs and benefits he faces if he does invade.

Brutal economic sanctions on Russia

Whatever Putin may have thought when he began his military build-up, he must now recognise that he faces devastating economic sanctions if he invades. He is partially prepared for them, but only partially. Russia has built up substantial central bank reserves ($600 billion) and has made fewer trade and investment ties with the West since the 2014 Crimean invasion.

A new set of western sanctions on energy and international banking transactions would effectively cut off Russia from western markets and new investment. That would be bad news for the whole country and especially for the oligarchs around Putin. Of course, the hit would work both ways: Germany would be particularly vulnerable to export slowdowns.

Much higher energy prices

Those would obviously hurt the entire global economy, including China (as a major energy importer), but would help Russia as a gas-producing country. Yet higher prices would mean Putin would be forced to sell almost everything to Beijing, which would (a) negotiate hard on prices and supplies, and (b) make Russia a subordinate partner, politically and economically.

Scholz and Biden’s drift

Berlin certainly wants to continue the Nord Stream 2 project, if it can. Merkel killed off its nuclear power after the 2011 Fukushima meltdown and deliberately made Germany dependent on Russian energy. Now that choice comes back to bite them. Biden has been very clear: he wants to kill Nord Stream 2 if the Russians invade.

How skittish is Berlin about that prospect? Well, their new Social Democratic Chancellor Olaf Scholz won’t even say the pipeline’s name in public. Nor will his government join other Nato members in providing Ukraine with the lethal aid it needs to fight (or deter) the Russians. In an embarrassing gesture, Berlin sent them a few thousand military helmets. At least they weren’t the old Prussian Pickelhauben, with the spikes on top.

Whatever Germany thinks, the United States is ready, willing and able to sever western ties — including Germany’s — to Russia if Putin invades. But while Biden is willing to impose those costs on America’s partners, he has shown no willingness to make hard domestic choices himself.

The crucial question is whether Biden will change his own anti-drilling, anti-pipeline, anti-oil-and-gas policies to help Europe and offset America’s own loss of Russian energy imports. So far, he’s shown no sign he’s willing to do that. Since day one of his administration, when he stopped the Keystone XL pipeline, he has followed the agenda of green-energy progressives. When he has needed oil, he has called on Opec to ramp up production. Their response? ‘Do it yourself’. Out of sight, out of mind won’t work for Biden forever: he might pay an higher price if energy prices soar.

Putin would be taking a huge political gamble at home

It’s a strange decision, since he already has a firm hold on power and would be risking it without needing to. Of course, success would bring some big political gains, beginning with his restoration of Russia’s status as a great power. He would also be extending the Kremlin’s grip over the ‘near abroad’, as Russian leaders refer to the old Soviet sphere of influence. In fact, he would be restoring part of the Czarist empire and part of the Warsaw Pact, where ‘independent’ states were really subordinate to Moscow and dependent on its military backing.

Putin could strengthen Nato, not split it

Western populations and their governments would be outraged by a full-scale invasion, which would kill innocent Ukrainians and show that Russia had no intention of letting the post-Cold War settlement stand.

If Putin thinks a demonstration of military strength — and his willingness to use lethal force within Europe — can intimidate Nato, he’s miscalculated. The early stages of his military buildup did reveal major differences within the alliance, but those will pale if he actually invades Ukraine. That action would revive the alliance and give it a clear-cut mission: to prevent further Russian aggression, especially against Poland and the Baltic states.

Finland and Sweden might well seek Nato membership, which would raise very serious strategic questions for the alliance itself, since Finland virtually shares St. Petersburg’s zip code. Finland’s membership, in particular, would outrage any Russian government and produce a strong pushback if Nato even considered it.

Putin faces a huge domestic risk if his military takes heavy casualties

Some might come during the invasion itself, but a long-term occupation of hostile territory poses an even greater danger.

Military analysts don’t think it will take the Russian army long to defeat a much smaller and weaker Ukrainian force. But before Putin stands in front of a ‘Mission Accomplished’ banner, he will surely remember the mortal wounds the Soviet Union suffered in Afghanistan. The population there was well-armed, well-organised and well-positioned to inflict a steady stream of casualties on an occupying force. The same is true in Ukraine. If Putin doubted that, he’s had weeks to watch the population training for urban warfare and years to witness the casualties in eastern Ukraine, where Russian and Russian-backed forces are under continuous attack. And he knows that region is far more pro-Russian than the rest of the country.

A puppet regime in Kiev can’t replace a Russian occupying force

Putin won’t be able to sidestep these risks by implanting a puppet regime. It simply can’t do the job. Putin ought to know that from hard experience. The last friendly regime in Kiev was driven out of the country when Putin forced it to drop plans for stronger economic ties with western Europe and forge them with Russia instead. The locals knew what that meant economically and politically, and they rose up and drove out the regime in 2014.

If history is a guide, then Russia will have to leave occupying troops in place across Ukraine, where local guerrilla forces will draw blood every day. That means body bags coming home to grieving families. It means beleaguered Russians asking, ‘What was it all for?’

The limitations of a partial invasion

Invading only eastern Ukraine would secure a land bridge to Crimea and limit Russian casualties, but it would incur most of the other costs the West threatens to impose. Putin might figure that the costs of a nationwide invasion wouldn’t be much higher. But that calculation omits the much greater costs of conducting a long-term occupation in hostile terrain.

China is watching

Just as Russia’s appetite for Ukraine was whetted by Biden’s botched withdrawal from Afghanistan, so China’s will be satiated if Russia doesn’t pay a high price for invasion. There are crucial differences, of course, between China’s military aspirations and Russia’s. An amphibious invasion is much more difficult than an overland one. And China has the troops for a full-scale occupation, if need be. But China has a much greater vulnerability, too. Its economy is far more dependent than Russia’s for trading and investment with the West. If Beijing sees Russia completely cut off from those major markets, it will have to take that economic threat much more seriously.

This will be the first full-scale cyber war

Russia is well equipped to stage it, not only on Ukraine but on western and central Europe and the US. No one has any experience with how such a conflict could escalate or the scale of civilian casualties it could impose. Biden, like all his European partners, has said Nato troops would not be involved in Ukraine. But Putin could reach out and launch cyberattacks on major western targets: everything from banking systems to electrical grids to hospitals. We have some experience coping with those attacks, but none deterring them.

Make no mistake. A major Russian invasion would impose huge costs, not only on the combatants and the political regimes in Russia and Ukraine, but on the whole world. It would, most likely, send us back into another iteration of the Cold War, with Russia allied with China, Iran and North Korea.

The prospect is a chilling one, and Putin’s hand is on the thermostat.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s World edition

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in