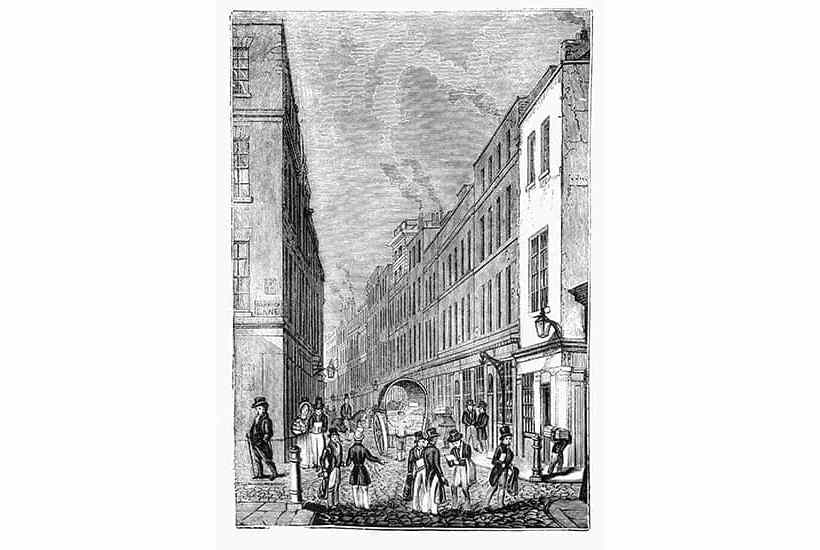

In the tight dark maze of alleys that wind between the Thames and St Paul’s the pleasures of the living are intertwined with those of the distant dead.

Try it for yourself on a late Saturday afternoon. Start by immersing yourself in the eerie darkness of the Temple of Mithras (ancient stones, reconstructed Roman voices calling for strong drink, a pagan pit beneath the guileless Bloomberg building); emerge and cross over to the Roman Watling Street, where you will see tribes of Essex women – Boudicca’s spiritual daughters – with faces of bronze, brandishing not fire but fags and lighters outside busy pubs and bars. Then on to the cathedral precincts, the air dotted with the clatter of skateboard obsessives, glowing with the reflected light of vast clothes emporiums and humming with diners and drinkers. The streets around other cathedrals throughout England usually seem to be on best behaviour. For some reason, as Margaret Willes explores in this wonderfully engaging book, the environs of St Paul’s Cathedral – old and new – have always attracted more contrary spirits.

The area is historically most associated with Paternoster Row and the genesis of the publishing trade, with all its attendant non-conformity and outbreaks of pornography. Willes gives a diverting account of searing political pamphlets, sexy literary scandals such as Fanny Hill and the first printing of literary sensations such as Lyrical Ballads, with walk-on appearances from Charlotte Brontë and Mary Wollstonecraft. There are also fascinating insights into the pioneers of children’s literature and the intricacies of copyright, all of which arose in the shadow of the churchyard. Many publishing houses, including Cassells and Oxford University Press, were still to be found there right up until the second world war.

Yet, as Willes demonstrates, this spot had been a crucible of history – a theatre of ideas and dissent – ever since William Rufus, the son of the Conqueror, had in the late 11th century backed the construction of a mighty cathedral of Caen stone with a steeple some 260 ft high, replacing its burnt out Anglo-Saxon predecessor. This was an even more startling Norman imposition on the skyline than the roughly contemporaneous Tower of London – exquisite, but also emphatic in its Gothic dominance.

As the centuries and the smoky London air darkened the cathedral’s stones, the threat of religious bloodshed was always close. The Reformation of the 16th century saw an outdoor pulpit in the churchyard – Paul’s Cross – become ‘all England in a little room’. Here epic sermons were delivered to vast crowds (with VIPs in specially segregated seating areas). John Fisher denounced Martin Luther; then, as the great pendulum of history swung, Thomas Cromwell arranged for a series of clerics to give sermons on ‘the King’s supremacy’. The pulpit’s proximity to the nascent printing trade meant that important sermons were copied and then printed and distributed often far beyond England’s shores. One of the towers of the pre-Wren St Paul’s was a prison for Protestant heretics during the reign of Mary. And it was at nearby Smithfields that their living flesh was melted in flame.

Yet the fires of conflict had been building for a great deal longer. In the 1400s, when John Wycliffe sought to render the scriptures in English for all to read, it was in the lanes around the cathedral that craftsmen covertly worked on forbidden Lollard bibles. Willes conveys not just the instability but also the beguiling strangeness of other traditions that arose in these precincts, including pig-owners allowing their animals to wander through the cathedral as a short cut. Something about it seemed resistant to quiet piousness.

When the roaring inferno that swept through London in 1666 brought it to its knees (the diarist John Evelyn picked over its ‘calcined’ ruins) and the new domed creation that was to take its place became a life’s work for Sir Christopher Wren, the churchyard still somehow held on to that rackety character. Around the mighty new edifice, dandies swaggered, coffee houses echoed with stentorian disputes and, nearby, fashion houses provided fine silks for elegant ladies. But there was always an awareness of the old gods: Wren’s workmen had unearthed ‘Roman urns, lamps… and fragments of sacrificing vessels’ as well as, says Willes, ‘a basin fragment showing Charon, the ferryman of Hades, greeting a naked ghost’. Like the grinning skeletons that featured in so many religious engravings produced here, there was a sense of a bracing attitude to death.

Swirling around all this was the cathedral’s curious relationship with the ever-growing city. Even the royals were never quite consistent in their attitude to it. Queen Victoria rarely set foot in the place, though it had become ‘the parish church of the British Empire’; but her successors relished opportunities for outdoor services in the churchyard, to say nothing of the crowds that gathered there for the 1981 wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer.

There might be one or two psychogeographers who loathe the new postmodernist Paternoster Square with its restored Temple Bar. But walk around it in the early evening: savour the son et lumière shows, the music, the floodlighting, the beauty. Londoners have taken this territory for granted for too many decades, and Willes is here to put that right.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in