It is tempting to believe that we have gone from one crisis to another: Russia invaded Ukraine hours after Covid restrictions were lifted in England. Tempting, but wrong. Covid is now manageable because of high levels of immunity from vaccines and prior infection (just look at how our high case rate isn’t leading to calls for the reintroduction of restrictions). But it remains problematic in less highly vaccinated countries, particularly those pursuing a zero-Covid strategy.

The most dramatic example is China. There are approximately 15 million unvaccinated over-eighties in the country (Beijing prioritised immunisation by profession rather than age). Even those who have been jabbed haven’t been given Pfizer or Moderna, two of the most effective vaccines, as they haven’t been approved in mainland China. Worse still, the previous clampdowns mean there is very little natural immunity in the population.

Hong Kong serves as a forewarning for what might be about to happen in China. Its death rate is currently more than double that of Britain at the peak of the second wave, with a daily death rate of 38 per million (the UK’s seven-day rolling average is 1.52 per million).

The Chinese authorities are clearly worried about what might be coming down the track. Shenzhen, the tech manufacturing hub neighbouring Hong Kong, has been put into lockdown for a week, with residents only allowed out for three rounds of testing. But China’s Covid problem is worse than a spill-over of cases from Hong Kong: Jilin – which is further from Hong Kong than London is from Tunis – has also been placed under severe restrictions. No one can leave the province without police permission.

Veterans of the UK’s Covid struggles believe the current strains of the virus are so transmissible that even the most draconian lockdowns won’t contain it. They expect cases to spike in more and more Chinese cities. With Beijing’s zero-Covid policy, the rise in cases will result in more lockdowns.

The effect on the world economy will be significant. Already the world’s third-largest port, Yantian in Shenzhen, is effectively shut for cargo operations. This means that suppliers are now ordering more than they need to guard against production interruptions. It’s inevitable that supply-chain problems will start to bite in a similar way to last autumn. Then you have to factor in the broader effect on global growth of the world’s second–largest economy being so disrupted.

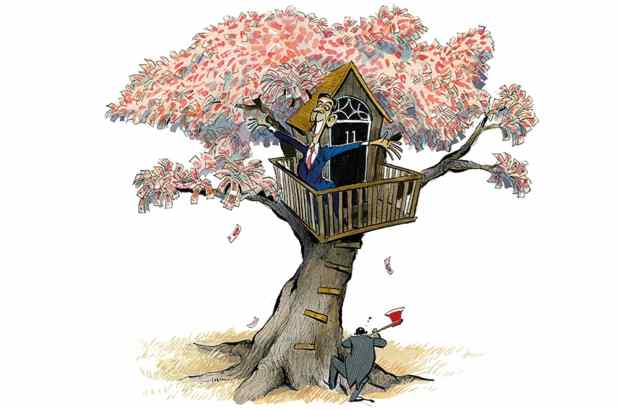

The markets are bracing for a hit: the Shanghai Composite was down 5 per cent on 15 March. It can also be seen in the price of oil: China is the world’s largest importer of crude, which is now close to $40 off its recent peak. That oil is back below $100 a barrel is a consequence of China’s Covid crisis. At the same time, it has taken some of the pressure off Boris Johnson’s request to Saudi Arabia, where he has recently visited, to increase oil production.

Senior figures in government were worried that expectations for the trip were out of kilter with its chance of success, given that Mohammed bin Salman is enjoying the increased power that the rise in oil prices has given him and the strain that has put on the Biden administration (which refuses to deal with him because of his role in the murder of Jamal Khashoggi). MBS should be careful, however: if it becomes clear there is little chance of the Saudis pumping more, then the voices calling for a quick nuclear deal with Iran – so that sanctions on its oil exports can be lifted – will grow louder. This would be a self-defeating move by MBS, given his concerns that too much is being offered to Tehran at the Vienna talks.

Then there is the question of what China’s worst Covid outbreak since Wuhan in 2020 means for its stance on Ukraine. Beijing has sought to blame the war on the US and Nato’s eastward expansion, and has spread Russia’s absurd claims about bioweapons labs there. Yet it has also been nervous about looking as if it is backing the invasion of a sovereign state. Beijing was uneasy with the way in which the US revealed Moscow had requested military assistance from China.

It is possible that China’s Covid situation will lead to it limiting itself to rhetorical backing for Moscow: a return to lockdowns would be the country’s focus, not a superpower proxy war in Ukraine. Regardless, the West should brace itself for more co-operation between Moscow and Beijing. The logic of my enemy’s enemy is my friend is strong enough with Putin and Xi to push them closer together.

The consolation is that the global West appears to have grasped the threat posed by Russia and China to the rules-based international order. Just look at how Japan, South Korea and Singapore are signing the sanctions; they know Beijing is watching closely to see what the consequences are for a state that attempts to redraw the map by force.

The sanctions have been co-ordinated by the G7, which has the benefit of bringing together the leading members of Nato with Japan. But a broader-based body would be ideal. When the UK hosted the G7 last year, Boris Johnson attempted to expand it by inviting South Korea, India, Australia and South Africa. But this grouping looks less promising after India and South Africa abstained in the UN General Assembly vote condemning Russia’s invasion.

In a speech this week, David Frost – Boris Johnson’s former Brexit minister – called for a ‘League of the West’ containing countries from across the world that are ‘broadly liberal’ and have an ‘interest in a peaceful and ordered arrangement of the world’. It may be simpler to begin with a smaller group; Russia’s list of unfriendly countries – dominated by the US, the UK, all EU members, Norway, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea and Singapore – would be a good starting point.

The combination of war and Covid will lead to a shortening of global supply chains as firms seek to make their supply lines more resilient. Even before China’s latest lockdowns, sanctions on Russia were causing companies to re-evaluate what would happen to their supply chains if China attacked Taiwan.

We have returned to a world where geopolitics trumps economics. One of the themes of this decade will be an economic and technological decoupling between the global West and the autocratic states that are determined to challenge the post-Cold War order.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in