If Brighton and Hove Council has its way, children as young as seven are to be taught about the ‘white privilege’ supposedly derived from 500 years of colonialism. But is it true that the history we have been learning from childhood has been infused with the great isms of our day – colonialism, imperialism and racism? I thought I would test this on a small scale by going back to the first history books I read.

H.E. Marshall, who wrote Our Island Story, was also the author of the knockabout book Kings and Things. She knew all about trigger warnings: ‘The story of England,’ she proclaimed, ‘is thought to be a story too frightening or too difficult for the very young person’s understanding.’ She promised not to dwell ‘on horror or on the glory of bloodshed’. She did not keep her promise – nor, surely, did her readers want her to. There is plenty of boiling oil poured from the castle walls, and Wicked Uncle Richard has a starring role before Henry VIII cuts off piles of heads. As for Empire, she bypassed the native population to emphasise how the ‘bothersome’ French kept getting in the way in North America. In both Marshall’s books notable people are generally Good or Bad, a way of thinking that sparked the famous parody by Sellar and Yeatman, 1066 and All That. Their book has been seen as a pioneering post-modernist attempt to debunk jingoistic versions of British history. That is surely to take their silliness more seriously than it deserves.

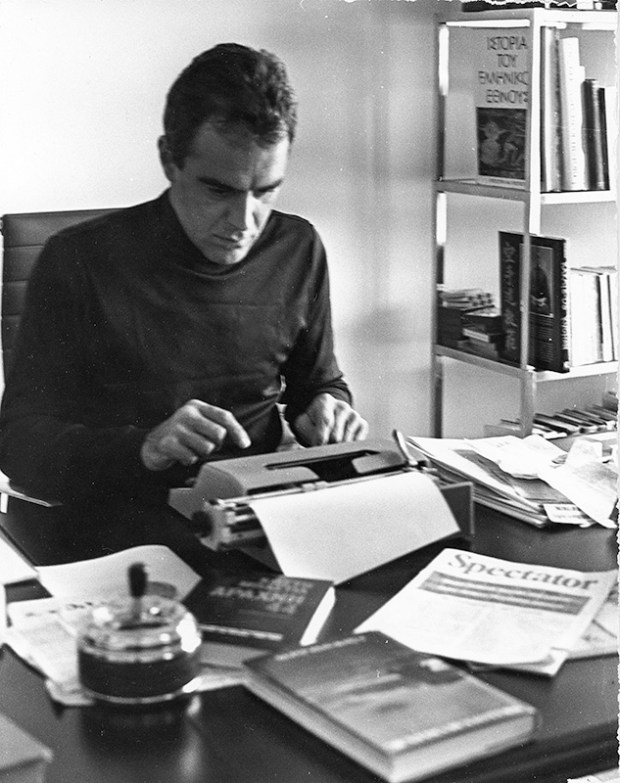

Beneath the flag-waving there were thoughtful ideas, as I discovered on returning to my first proper history book, given to me as a birthday present: A Nursery History of England by Elizabeth O’Neill. It is filled with glossy colour illustrations which are still locked in my memory, influencing the way I imagine scores of events in history. The book first appeared in 1912 but kept selling and was constantly updated. O’Neill was for a time a fellow at Manchester University and was married to Herbert Charles O’Neill, who wrote a celebrated Spectator column during the second world war under the nom de guerre Strategicus.

O’Neill set out her aims in another of her books: ‘I have chosen the greatest men and women to tell you about, and in reading their stories I hope you will understand better something of what the times were like in which they lived, and what the other people too were like who were not so great and the kind of lives they led.’ O’Neill did not neglect what would nowadays be called the history of gender and class. We have the Countess of Buchan displayed in colour crowning Robert the Bruce. Queen Matilda and Queen Margaret of Anjou are shown escaping from capture. Further down the social scale Jenny Geddes is portrayed hurling her stool at the preacher when he started reciting from the English Book of Common Prayer in Edinburgh’s St Giles’ Cathedral.

O’Neill was indignant about the horrors of slavery. The hot conditions in America did not suit English settlers, ‘so black men, from a country called Africa, were stolen away from their homes and taken over to America. The white men bought them, and made them do the hardest work… They had to do just what their masters told them, and cruel masters often used to beat them’. The slaves ‘were bought and sold as though they were animals’. One of her heroes was Charles James Fox, for standing up for the slaves in parliament. She also condemned child labour during the Industrial Revolution, this time with an illustration of barefoot, ragged children on their way to the ‘big ugly workrooms’.

She was, admittedly, interested in people’s physical appearance, and delighted in describing early Britons or Saxons as golden-haired and blue-eyed. She relished the story of how in the 6th century Pope Gregory the Great had seen blond Anglo-Saxon children in the slave market in Rome and commented that they were non Angli sed Angeli, ‘not Angles but Angels’. We are now being assured by graduate students at the University of Leeds that the term Anglo-Saxon should be abolished because it developed ‘as a concept intrinsic to the emerging ideologies of colonialism, nationalism, and white racial superiority’. As an eminent medieval historian commented: ‘But theywere the victims of Norman colonisation in 1066.’

Looking at the British Empire, O’Neill was most interested in India, ‘a very hot country’ whose people ‘have dark skins and black hair. Some people from this country used to live in India to help to rule it’. That led to resistance from those who thought the British had been ‘unkind’, but ‘Indians are very brave fighters, and thousands of Indian soldiers helped to win both world wars’. Gandhi ‘was a very great and good man’.

Rather than delivering a jingoistic account of English history, O’Neill was generally careful to maintain a balance. She was keen on godliness and steered carefully between Protestants and Catholics, giving full marks to Thomas More and high marks to Thomas Cranmer, shown at the stake. There were genuinely good people like Thomas More and Florence Nightingale who would serve as an example to the young, and there were thoroughly bad ones like King John. But it is important to recognise that her book was not a paean in honour of national heroes. Even Nelson, who unusually earned two colour illustrations, is praised for his skill and bravery as a naval commander, but not made into an icon. She recognised Napoleon’s military genius and was inspired by England’s foe Joan of Arc.

Overall, the Nursery History is a humane attempt to tell what she hoped would be a balanced version of England’s story to young children. Would that this were the case with modern narratives of history that evoke injustices of long ago in order to cast blame on the citizens of 21st-century Britain.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.