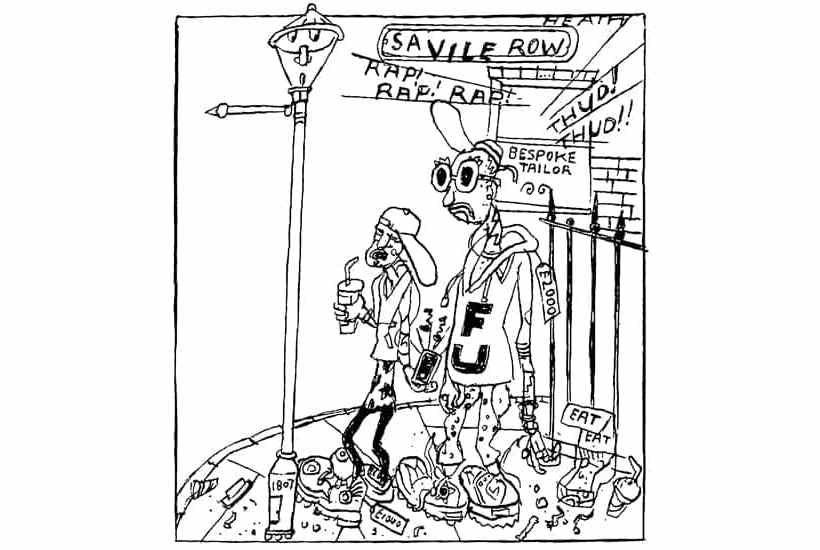

Huntsman, at No. 11 Savile Row, was once an understated beacon of good taste. But if you visit today, you are likely to be met by a gaggle of tourists posing for selfies in front of the window across which is splashed in very large letters: ‘The King’s Man, only in cinemas now.’

The tailor, which dressed the Duke of Windsor in his bachelor days, provides both the inspiration and location for this fun, if silly, spy movie franchise, the latest of which stars Ralph Fiennes. Unfortunately, cinematic fame has led to the brand losing its bearings. Pop inside and you are confronted by a selection of what can only be described as knick-knacks for the vulgar: a £5,500 tweed and leather backgammon board, a £1,200 gun slip in Gregory Peck tweed and a pair of £599 tweed headphones.

It is not the only British brand that has embraced tackiness in a headlong rush to win over new customers. Around the corner, on Regent Street, is Penhaligon’s. The perfumier used to supply your grandmother’s soap and Bluebell bath oil; now it wants to tell you a story. Its most recent range is called Portraits. Each scent, we are told in breathless descriptions, represents a member of a supposedly aristocratic family. There’s Heartless Helen, Terrible Teddy and Duchess Rose, who is ‘urgently desirous of desire. Her bosom is aching for release from the corsets of Victorian life’. Each 75cl bottle, priced at a decidedly unfragrant £210, comes topped with a gold animal head. Dear God. What is going on?

Barbour, whose waxed jackets have kept the rain off generations of huntin’, shootin’, fishin’ types, has launched countless diffusion lines, including Barbour International, whose children’s range includes – and I shudder to write this – track pants, which feature ‘Barbour International’ written repeatedly down the side seam, as if they were designed for the junior inmates of HMP Wandsworth. ‘The original Barbour customer is dying, the company has to look at opening up their brand,’ says Nick Ede, a brand expert who studies popular culture movements. ‘Asian customers are more interested in branding than old-school shooting and black-lab types.’

Maybe. And it’s true there are more millionaires in China than in the UK. But this is a dangerous game to play. Rolls-Royce, with its Cullinan SUV, and Mulberry, with its £125 bucket hats, need to watch out. Twenty years ago, there was the ultimate case study in what happens when a brand suffers from ‘prole drift’, to use the wonderfully snobby term coined by American author Paul Fussell to describe the phenomenon of a company attracting the wrong sort of customer. Burberry has subsequently recovered, but for a few years it became ‘a badge of thuggery’ – the description given to it by one Dundee pub landlord who barred customers if they were wearing its distinctive check.

One brand that has suffered from similar drift and hasn’t managed to recover is Jack Wills. It was once the most sloaney of teenage fashion labels, sponsoring the Eton vs Harrow polo match. But since it has been taken over by Mike Ashley of Sports Direct, private school kids know it is social anthrax to be seen in one of its hoodies.

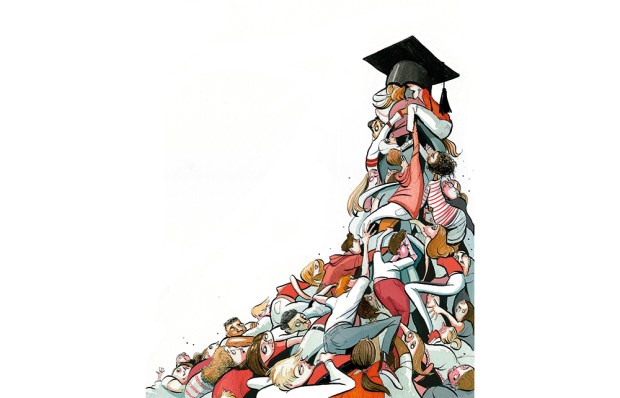

Some of the blame can be levelled at the owners. A mixture of international luxury-goods conglomerates and trophy-hunting billionaires have snapped up some of the smartest British firms, failing to understand that what made them special in the first place was a certain restraint. How else can you explain Church’s, the dependable brogue-maker, selling £690 Mach 3 trainers? ‘We would suggest playing up [their] leisurely, trend-aware mood with oversized jeans, T-shirts and unashamedly edgy sportswear,’ suggests the company, now owned by Prada.

Richard Caring, the creosote-faced Croesus of the clothing world, has hoovered up restaurants as well as Annabel’s nightclub, once a haunt of royalty and rock stars. Now it’s a place for hedge-fund managers and oligarchs, and for their mistresses to trout-pout their Botoxed faces in the ladies’ (‘The most Instagrammed room in Britain’, according to Caring). In a recent interview, he proudly explained how one guest had booked out the entire women’s lavatory for a party with champagne and caviar. He now wants to roll out Annabel’s to Paris, New York and Saudi Arabia. It is an example of yet another quintessentially British brand being co-opted as a plaything for global plutocrats and reduced to a social media backdrop.

Mayfair and St James’s used to be home to some of the smartest establishments in the world. It feels as if many of them are vying for a slot in a Dubai shopping mall, where every brand must be ‘reimagined’ into a pair of cufflinks or a dreaded scent diffuser.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

spectator.co.uk/podcasts Harry Wallop and Nick Ede on British brands.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in