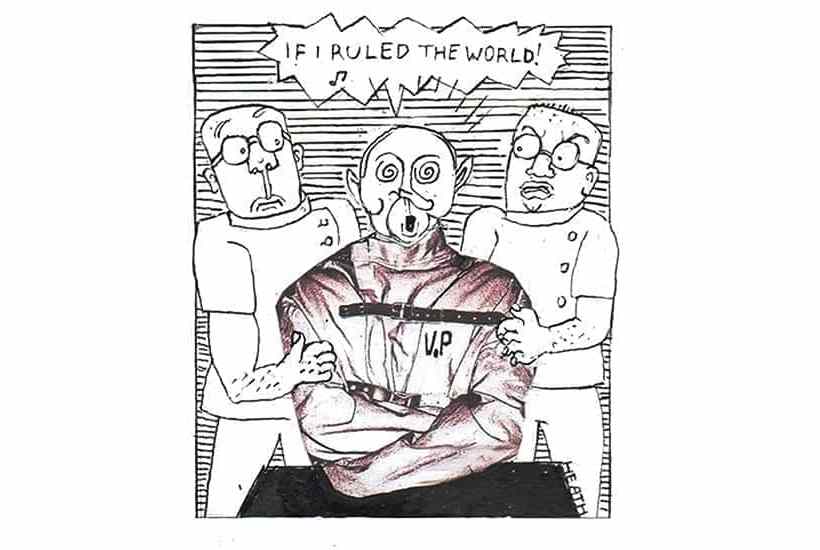

I wish people would not say Vladimir Putin is mad. One understands him much better if one says he is bad. In some ultimate sense, evil is a form of madness because it brings destruction to its perpetrators as well as its victims, but Putin is not mad in the ordinary sense of the word. He knows what he is doing. The value of saying something like ‘He would happily murder every single Ukrainian if it served his purpose’ is not to express one’s anger and disapproval (both of which should be obvious) but to shed light on his attitude of mind. Given that he is such a person and his purpose is the re-creation of the Russian empire, the western allies cloud their own minds by seeking a conventional diplomatic path. James Sherr, the sage of the Estonian Foreign Policy Institute, tells me of his exasperation at the first question asked of him recently in an interview with a leading western newspaper. It was: ‘What possible off-ramps do you see for Putin?’ The answer is: ‘None.’ Putin has studied the western culture that believes in ‘off-ramps’ for more than 30 years, despises it and now thinks he knows how to beat it. If we continue to think in terms of diplomatic solutions, Putin will know he can get more by behaving worse. So far, Boris Johnson is the only major western leader, I think, who has specifically said that Russia must be defeated and be seen to be defeated. Defeated, not accommodated. Hence the warmth of the thanks President Zelensky gave in his video speech to the House of Commons on Tuesday, and hence too his challenge to the West as a whole. ‘By failing to do what we can do, we keep thinking we’re showing restraint,’ says Sherr. ‘We are simply presenting a vulnerability and a temptation to an aggressor to widen the war he has started.’

October 1917: Ten Days that Shook the World was Eisenstein’s memorable 1927 propaganda film for Bolshevik communism. In the Commons, President Zelensky spoke, presumably with a conscious echo, of his country’s ‘Thirteen Days of Struggle’. It has the makings of a great movie. It is about 50 years since I saw the Eisenstein silent, but I think I remember the scenes of the crowds shouting, and the words ‘Peace!’ ‘Bread!’ ‘Freedom!’ filling the screen. I think Lenin calls out the same words when he speaks. He was not good, of course, at providing any of these things. If Zelensky wins, there is every prospect of Ukraine having all three, and inspiring a film with a genuinely happy ending.

The most endangered country after Ukraine is now Poland, the major Nato member which best understands the Russian threat. In Putin’s overheated picture of Russian history, Poland is the image of the enemy. It is also the pivot of Nato’s military power in east-central Europe. Every four years, for some time, the Russians have conducted major ‘Zapad’ (‘West’) military exercises, mainly in Belarus. In 2009, the Zapad wargame was that the Poles had intervened in favour of their ‘compatriots’ in Belarus, the Russians had responded with a counteroffensive, and the end came with a Russian nuclear strike on Warsaw. Observers such as Sherr noticed an element of Russian wish fulfilment here, but also a read-across: for Belarus, read Ukraine. Poland is now the first main point of arrival for refugees and the principal place where weapons can cross to support the Ukrainian government. Putin has already said he would he regard a no-fly zone as a declaration of war. He has said the same about the imposition of sanctions and the transfer of western aircraft which Poland is trying, and failing, to get America to back. Have the allies worked out how vigorously they would respond if the Russians start to attack shipments crossing the Polish border?

Although there is too much wishful thinking in the idea that Russia is unable to win in Ukraine, it is interesting that its multi-pronged offensive to occupy and control has stalled. If it is true that it has lost 12,000 men, that is a great many in less than a fortnight. The army seems tired and demoralised, short of petrol and munitions. It is hard to imagine Russians at home revolting spontaneously, but if the army crumbles, that is a different matter. After the Crimean war, the Russo-Japanese war, the first world war and, in the 1980s, Afghanistan, failure in battle was the catalyst of dramatic change at home.

The war in Ukraine has renewed media attention to Evgeny Lebedev, ennobled in 2020 at the wish of Boris Johnson. There were, apparently, tussles with the security services about whether he should have been granted the peerage, because of his supposed links with Putin. I know nothing about these, but the tussle about his title itself was amusing. His first request, apparently, was that he should be Lord Lebedev of Hampton Court, since he lives in Stud House, a large rented property on its estate. This was not permissible, however, since Hampton Court is a royal palace. His second preference was to be Lord Lebedev of Moscow, but this was not favoured either. Peers can normally take the title of a foreign place only if they have conquered / liberated it or won a battle there e.g. Earl Mountbatten of Burma or Viscount Montgomery of Alamein. Young Evgeny had not achieved this feat. Someone ingeniously discovered that there is a Scottish village called Moscow, so Evgeny could have become Baron Lebedev of Moscow in the county of Aberdeenshire, but that did seem rather silly. So he ended up with the ‘name, style and title’ of ‘Baron Lebedev of Hampton [the Court omitted] in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames and of Siberia in the Russian Federation’, which seems rather silly too.

Did you know that you can give money to the Ukrainian armed forces? Just go to bit.ly/uk-raine and the National Bank of Ukraine will help.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in