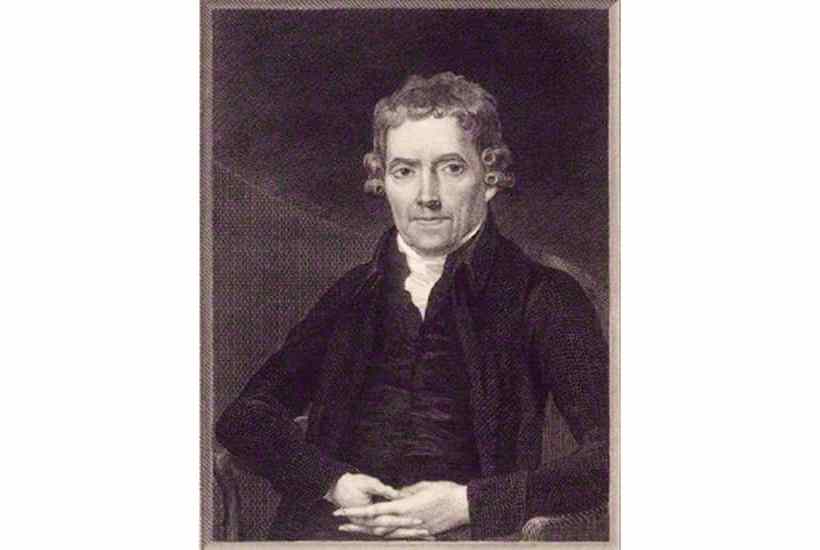

There’s no excuse for dullness, especially when writing about a life as eventful as Joseph Johnson’s, the publisher and bookseller who worked with Mary Wollstonecraft, Joseph Priestley, William Cowper, Erasmus Darwin and Wordsworth and Coleridge, among others. I opened this book expecting it to lift the veil on dinner with Joseph Johnson, but the title’s a misnomer. (Other than a brief introductory passage, Johnson’s weekly dinners are mentioned only in passing.) Descriptions of his relationships with Wollstonecraft and Cowper are perhaps the most successful parts of Daisy Hay’s book, but elsewhere it is under-researched and under-written.

This becomes evident early on when she writes about the Gordon Riots. Among the crowds, William Blake watched with mounting horror the incineration of Newgate gaol and all those inside. Scholars suggest the experience led him to associate fire with revolution, and so left its mark on his psyche and poetry. But Hay omits all mention of Blake, despite his being a principal actor in her story – a shame, because he could have brought her account to life.

Again, Hay says that Richard Lovell Edgeworth ‘narrowly escaped being lynched by a loyalist crowd after he was accused of aiding the rebels’ and that Edgeworthstown, in Co. Longford, was nearly destroyed by ‘rebels’, but with no explanation of who they were. That is to say, she makes no mention of the United Irishmen and therefore cannot refer to their uprising in 1798, let alone the subsequent French invasion expected in August that year.

Such derelictions are hard to forgive. However shameful it may have been, that chapter is an important one in our colonial history, and many readers won’t know about it. The arbitrary executions of those ‘rebels’ have no place in the curriculum of English schools, though there can be few people in Ireland who have forgotten the truth of it.

Johnson’s dealings with the Romantic poets ought to take a starring role, but Hay’s account of Coleridge’s Fears in Solitude volume focuses on the title poem rather than ‘France: An Ode’ or ‘Frost at Midnight’. This is like thinking you can do justice to Lyrical Ballads by writing about ‘The Convict’ when the real star is ‘Tintern Abbey’. ‘Frost at Midnight’ is one of the greatest of Coleridge’s conversation poems. That Johnson was its publisher is a significant part in Hay’s narrative, more so than she believes.

Part of the problem is that her characterisation is limited. She describes Wordsworth’s encounter with Johnson in 1793 with no sense of what the young Lake poet was like. At this stage his political views were similar to those of Robespierre: he thought regicide a fine idea, especially in the cases of Louis XVI and George III. If, as she suggests, Wordsworth was Johnson’s dinner guest, such convictions would have made for fiery exchanges, but she gives no hint of that.

Reading this book one senses that the drudgery of assembling fact after fact has been enough for Hay, without the forlorn challenge of bringing that swaying edifice to life. Of course there is also a problem of scale. Johnson was born in 1738 and died in 1809 – a life spanning decades of history and involving many writers. To do justice to the subject would require much time, and perhaps lack of it may explain Hay’s omissions.

There’s little here, for instance, about the Bluestockings. They are mentioned on page 78, but the term goes unglossed – as if everyone knows who Mrs Montagu, Hannah More and Ann Yearsley were. Nor is there any reference to ‘The Recluse’, the poem Coleridge had designed to precipitate Christ’s 1,000-year rule on Earth, which he would certainly have spoken about had he dined with Johnson in the summer of 1798. Nor does Hay mention the execution of Louis XVI and the arrival of the news in London – an event that changed the lives of everyone in Johnson’s circle, not least Johnson himself.

These aren’t minor details but elements fundamental to Hay’s project, and without them, it lacks definition, licensing the kind of narrowness that precludes imaginative truth and allowing the book to wander from one episode to another – unpersuasive, hollow and fuzzy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in