In just over a week’s time, Emmanuel Macron will most likely win a second term. He has the opponent he wants in Marine Le Pen, whom he believes will be too unpalatable for the French people. He hopes voters will fear that, unlike in 2017, she has a reasonable chance of victory – polls show just a few percentage points between the two candidates – and be persuaded to vote for him instead. If Macron’s strategy succeeds and he returns to power, it may seem as if nothing has changed in French, and indeed European, politics.

But even if Macron sees off a populist challenger for the second time, a strong showing by Le Pen threatens to destabilise his administration. He may not keep his majority in the parliamentary elections. The French presidential race fits a growing trend across Europe. On Monday the far-right Vox party entered government in the Castile and León region of Spain as coalition partner of Alfonso Fernández Mañueco. In many European countries, the establishment parties have struggled to respond to new concerns about immigration and globalisation. Voters have noticed.

It was not long ago that French politics was dominated by traditionally centre-left and centre-right parties: socialists and republicans. The two parties last slugged it out in 2007 and 2012, with the UMP’s Nicolas Sarkozy winning the former, and the Socialists’ François Hollande triumphing in the latter. In last week’s first round of voting, these two parties could between them muster only a derisory 6.5 per cent of the vote. They are unable to find the policies or the language to command mass support.

Over the past few decades, the division in western politics had tended to be between centre-right parties which combine economic liberalism with social conservativism, and centre-left parties which did the opposite. Now the schism tends to be between populist parties that are socially conservative but economically interventionist, and which therefore appeal to traditional left-wing voters – and liberal parties, which are more internationalist in outlook and appeal more to the metropolitan middle classes.

Le Pen seems to have understood this shift. In order to mount a serious challenge to Macron, she has moved economically to the left. She stands for big government and high public spending, more so than when she last faced Macron in 2017. By positioning herself in this way, she has managed to appeal to large numbers of working-class voters who previously would have backed left-wing parties. The left-wing candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who was only 1.1 per cent behind Le Pen in the first round of the election, has said that ‘not a single vote can go to Madame Le Pen’. However, many of his supporters have already signalled that they feel more drawn to Le Pen than to Macron, whom they see as aloof and more interested in green policies than in their living standards. The gilets jaunes vote is not going to Macron.

Macron has been complacent. He has not even tried to rule for the whole nation of France; his method of government has involved pouring scorn on anyone who does not share his liberal, internationalist views. He has failed to find an effective way to deal with a populist opposition, in spite of having had five years to prepare for a second clash with Le Pen.

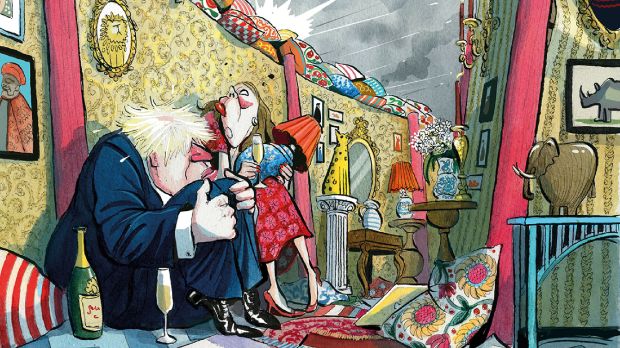

Some have attempted to make a comparison between Le Pen’s growing popularity and influence in France and the Conservatives’ 2019 victory in former red-wall seats in England. Yet this is wrong. Much as Boris Johnson has tilted towards larger government (as our rising tax burden attests), he is worlds away from Le Pen. While she has promised to ban Muslim women from wearing headscarves in public, Johnson’s infamous Daily Telegraph article in which he referred to women in niqabs resembling letter boxes explicitly called for people to be allowed to wear what they like.

While Le Pen advocates protectionism, Johnson says he stands for more open trade policies – indeed, many Labour politicians have condemned him for championing free trade beyond the borders of Europe. His problem is that he has failed to deliver on this vision. The lower prices he promised in the Brexit campaign have not materialised.

Though the Conservatives’ opponents would love to argue otherwise, Britain is one of the few countries in Europe with no populist figures either in parliament or with any sizable support in the opinion polls at the moment. Populism can be a sign of extremist views, but it is also a sign of voter despair when mainstream politicians fail to adapt.

As voters’ concerns change, this needs to be reflected in the politics. What troubles voters now, in the UK as in France, is the cost of living – Le Pen has made keeping oil and food prices low central to her campaign. Johnson might see, in France’s uncomfortably close election, a forewarning of what may await him if he cannot find a way of converting his low-tax, free-trade talk into meaningful action.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in