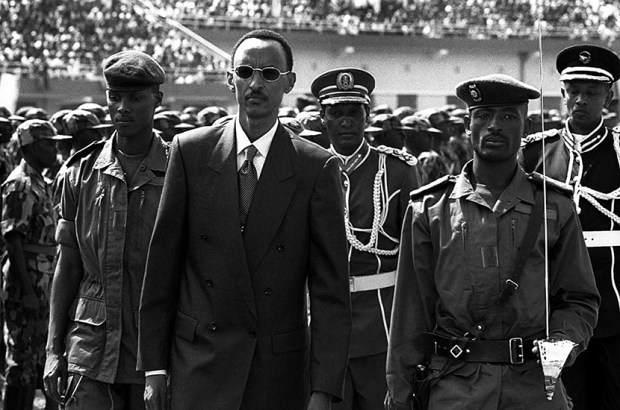

If President Paul Kagame has been tracking the furore over Priti Patel’s plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda, he’s been doing it on the hoof. Kagame moves constantly these days: the news broke while he was en route to Barbados after a visit to Jamaica. In the past two months he has been to Congo-Brazzaville, Kenya (twice), Zambia, Germany (twice), Egypt, Jordan, Qatar, Mauritania, Senegal and Belgium.

How the president of one of Africa’s poorest nations can afford all this travelling is a puzzle, and the fact that his Gulfstream jet is supplied by Crystal Ventures, his Rwandan Patriotic Front’s monopolistic investment arm, raises interesting budgetary questions. In a country where checks on the executive have been whittled away, the dividing line between a ruling party’s business interests and the presidential expense account is distinctly blurred.

Rwandan opposition critics wonder if he is scouting where best to stash his assets in preparation for the day every African leader dreads, when a military coup dispatches him into exile. Others speculate he just feels safer on the road, validated by every red carpet and guard of honour.

More likely, the globetrotting forms part of a decades-long drive to establish Kagame as Africa’s de facto leader-in-chief, not only an indispensable partner for any western government engaging with the continent, but a source of radical solutions to nagging domestic problems. While running a country only slightly larger than Sicily, Kagame punches so far above his weight, the boxing ring looks dwarfed by his presence. He is the Mighty Mouse of the African Great Lakes.

It’s clear why it suits Ms Patel to send her political undesirables to Rwanda. Back in 2003, Oliver Letwin, then the shadow home secretary, spoke about sending asylum seekers to a foreign island ‘far, far away’ – but the problem was finding a place that would agree. In Kagame, they have found someone who craves the limelight and is hugely skilled at identifying western needs. In return he seeks an airbrushing of regional history – and support for a narrative that presents him as a leader who single-handedly brought peace to a genocide–devastated nation and oversaw a developmental miracle.

In July last year, after a jihadist group paralysed a $20 billion liquefied gas installation run by France’s Total in Mozambique, it was Kagame who dispatched 1,000 Rwandan soldiers and policemen to Cabo Delgado to send the rebels packing. Long before Patel flew to Kigali, Denmark’s government had been discussing a similar offshore arrangement, and before that, Rwanda agreed to take in thousands of Eritrean and Sudanese asylum -seekers whom the then Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu wanted rid of.

But for these arrangements to be acceptable to domestic audiences – and to portray Rwanda as a safe place – Kagame’s western partners must gloss over one of the most sinister human rights records of any current African regime. And that is not easy, given how much evidence is in the public domain.

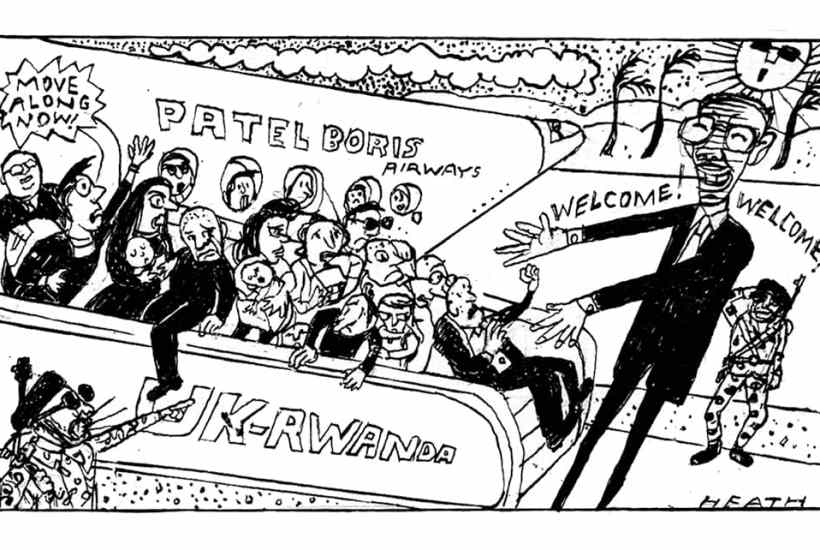

What was striking about the statements made by Boris Johnson, Patel and Tom Pursglove last week was their blank ahistoricism. Rwanda is ruled by a political party with a 32-year record of human rights violations – the killings date back to before the movement seized power in 1994 – but this was omitted from the spin about the ‘UK-Rwanda partnership’ for which the Home Office has designed a snappy logo.

It’s understood that Patel had to issue a ‘ministerial direction’ for her plan, overruling staunch and formal objections from her department. Perhaps Home Office officials thought it odd to portray as safe a country implicated in the slaughter of tens of thousands of Hutu civilians in the forests of neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo in 1996 and 1997. UN investigators logged hundreds of atrocities committed by Rwandan troops, in cahoots with Congolese rebel allies – some 100,000 people remain unaccounted for.

The UK-Rwanda partnership also glosses over a recent report by Freedom House in which Rwanda was cited for its track record of ‘transnational repression’: the systematic assassinations, attempted killings, kidnappings and intimidation of opposition leaders, human rights activists and journalists the world over. In 2011, the Metropolitan Police felt impelled to warn three exiled Rwandan activists living in London that their government was trying to have them killed.

Kagame has played this same game superbly with France, whereby a judicial investigation into who downed the plane in which the late president Juvénal Habyari-mana was travelling has been shelved, allowing President Emmanuel Macron to publicly embrace a man his predecessors once tried to arrest.

In return for exculpation, Kagame has repeatedly offered up his army, sending troops into places where western governments have no intention of sending their own men: hotspots like the Central African Republic, South Sudan, Darfur, Mali and Haiti.

Sceptics might argue that whatever happened to the Hutus in those forests, and whatever the gruesome fate of Rwanda’s former interior minister – shot in his car in Nairobi – or its former head of external intelligence – strangled in a South African hotel room – the regime treats non-Rwandan arrivals decently enough. United Nations chiefs, after all, recently commended Rwanda for its reception of hundreds of refugees airlifted from Libya’s detention centres.

But even that record is patchy. In 2018 the Congolese inhabitants of Kiziba, one of Rwanda’s six refugee camps, protested at having their miserly $9 monthly food rations cut to $6. Rwandan police opened fire on a demonstration, with a dozen killed. Community leaders from the camp were prosecuted and are still in jail.

And if the aim is really for those flown to Rwanda to ‘settle and thrive’, the question becomes how easily a system in which killings and disappearances are commonplace and freedom of speech impossible will absorb thousands of single men already fleeing repressive regimes. Many of the Eritreans and Sudanese flown to Rwanda from Israel simply hit the road again.

We can expect none of these issues to get an honest airing as long as Britain pursues this offshore deal: Britain, like France, will have instead made the transition from engaged, occasionally critical bilateral donor to Stepford Wife-style complicity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in