In my wife’s home city of Wroclaw, there’s a luxuryhotel named after John Paul II. It has always seemed strange that the Catholicchurch sanctioned this. Giant chandeliers and glitzy bathrooms weren’t reallywhat St John Paul stood for, and since the hotel opened in 2002 it had seemedas much a monument to the church’s decline as a tribute to a saint. Buteverything changed with the war in Ukraine. Some 2.5 million Ukrainians havefled to Poland since Russia’s invasion and the hotel is currently home to morethan 100 refugees. It’s as if the building has finally discovered its realpurpose.

What’s true of the John Paul II hotel is truemore widely of the Polish Catholic church. The response of Polish Catholics tothe war was immediate, all-out and magnificently unbureaucratic. A vast chainof care was formed that ran from nuns offering cups of tea to exhaustedrefugees at the Ukrainian border, to counsellors giving psychological supportto terrified children, to the archbishop welcoming new arrivals to stay in hiscavernous palace. This great humanitarian effort is all the more remarkablebecause the Polish Catholic church appeared, until very recently, to bedemoralised and adrift. Its reinvigoration could hold some lessons for thewider church – not just the Catholic church, but the Church of England too.

For many, the words ‘Polish Catholicism’ evokeimages from the 1980s: of dissidents speaking at shipyard gates in front ofpictures of the Virgin Mary, vast crowds assembled for the funerals of martyredpriests, and John Paul II, dashing in his red cape. But it’s time to updatethat picture, because the Polish Catholic church has changed greatly.

Following the Pope’s death in 2005, it beganto lose its way. The most obvious sign was the abuse crisis. Disturbingdisclosures led the Vatican to punish a series of bishops for negligence: ahumiliating twist for a church that had enjoyed such moral prestige. Trustvanished, especially among young Poles. One survey found that only 9 per centviewed it positively. It wasn’t just abuse that troubled them: it was also thehierarchy’s perceived alliance with the polarising Law and Justice party, whichhas led Poland since 2015.

Anti-church sentiment exploded in 2020 after afurther tightening of the country’s strict abortion laws. Young protestorsdisrupted Sunday masses and daubed Poland’s ubiquitous statues of John Paul IIin red paint. These once inconceivable acts suggested a radical shift in Polishsociety.

The church’s internal weaknesses were becomingever more apparent. Mass attendance, baptisms and marriages were all falling,while the number of men enrolling in Poland’s seminaries dropped by a fifthlast year. Looking at this picture just a couple of months ago, you might havethought that the Polish Catholic church was a spent force. But you would havebeen wrong.

In their outpouring of charity towards Ukrainian refugees, Polish Catholics havecome to embody one of Pope Francis’s most powerful intuitions: that the renewalof the church comes through service. (This is somewhat ironic given the Polishchurch is often accused of being out of step with Francis.) In his first majorinterview as Pope, Francis said: ‘I see clearly that the thing the church needsmost today is the ability to heal wounds and to warm the hearts of thefaithful; it needs nearness, proximity. I see the church as a field hospitalafter battle. It is useless to ask a seriously injured person if he has highcholesterol and about the level of his blood sugars. You have to heal hiswounds. Then we can talk about everything else.’

Obviously, the Pope is not the first Christianleader to emphasise service, but there is an unusual urgency to Francis’smessage. He believes that we are no longer living in normal times, and thebeauty of the ‘field hospital’ idea is that it applies not only to Christianitybut all world religions. In Judaism, for example, there is the concept of pikuachnefesh: that the preservation of human life overrides almost any religiousrule. So, for example, members of an Orthodox Jewish team worked through theSabbath to save the injured after the 2010 Haiti earthquake.

Charity is so central to the Muslim faith,meanwhile, that it is one of the Five Pillars of Islam. In Syria today, WhiteHelmet rescuers are consciously putting into practice the words of the Quran:that ‘to save a life is to save all of humanity’. As war, disease, poverty andfamine stalk the world again, believers can draw on these principles and givethem fresh expression, revitalising themselves in the process.

If this sounds a little abstract, thenconsider two lives that embodied the priority of service. The first is that ofElizaveta Pilenko, a Russian noblewoman who was so engaged in revolutionarypolitics in her youth that she plotted to assassinate Leon Trotsky. Forced intoexile, she settled in Paris, where she took religious vows. Mother MariaSkobtsova, as she became known, was an unconventional nun. Chain-smokingcigarettes, she turned her convent into a home for refugees. Her habit ofleaving communal prayer to answer the doorbell scandalised some of her fellowbelievers.

Explaining why she put the needy first, shewrote: ‘The way to God lies through love of people. At the Last Judgment, Ishall not be asked whether I was successful in my ascetic exercises, nor howmany bows and prostrations I made. Instead, I shall be asked: did I feed thehungry, clothe the naked, visit the sick and the prisoners? That is all I shallbe asked.’ After the Nazi occupation of France, she offered shelter to Jews,was arrested by the Gestapo and died in a gas chamber at Ravensbrück in 1945.She was recognised as an Orthodox Christian saint in 2004.

Her life had many parallels with that ofDorothy Day. After throwing herself into left-wing politics in 1920s New York,Day became a Catholic. Her faith offered a new outlet for her social activismand she co-founded the Catholic Worker Movement, which offered hospitality tothe homeless. She remained clear-eyed about the destitute to whom she dedicatedher life: ‘There are two things you should know about the poor: they tend tosmell, and they are ungrateful.’ Both Skobtsova and Day sought salvation inradical politics but found it in the unglamorous service of the poor. Perhapstoday’s upheavals will produce others like them.

It would surely be naive to think that theglorious philanthropic upsurge in Poland will reverse the decline inchurch-going. When we hear the word ‘renewal’, we tend to think only of anincrease in numbers. Yet it’s possible to conceive it differently: as aninternal reinvigoration.

In 1969 – another year of epochal change –Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, devoted a radio address to thetopic: ‘What will the future church look like?’ Peering decades ahead, heforesaw an institution that had lost much of its past prestige.

‘She will become small and will have to startafresh more or less from the beginning,’ he said, predicting that the ‘realcrisis’ had barely begun. ‘We will have to count on terrific upheavals,’ hewent on. ‘But I am equally certain about what will remain at the end: not the churchof the political cult, which is dead already, but the church of faith. It maywell no longer be the dominant social power to the extent that she was untilrecently; but it will enjoy a fresh blossoming and be seen as Man’s home, wherehe will find life and hope beyond death.’

The Christian church is shrinking in the West,as Benedict XVI said, but this doesn’t have to be a disaster. There were just12 disciples who were convinced that they had witnessed the death andresurrection of their teacher. Somehow this was enough to transform the world.

There are some interesting similaritiesbetween the Church of England and the Polish Catholic church. Both areguardians of national identity with unrivalled parish networks. If the refugeecrisis has helped Polish Catholics recover their sense of purpose, couldn’t asimilar challenge do the same for Anglicans? According to one estimate, 1.3million Britons will be pushed into absolute poverty by the cost of livingcrisis. Could the C of E lead an effort to help them? This would tap into afine British tradition of Christian social engagement that includes theSalvation Army, with its work among Victorian gamblers and drinkers, andAnglo-Catholic ‘slum priests’. This is not an encouragement for the C of E toplay politics or grandstand on Twitter – it is about actual service.

While the decline of the Polish church isreal, it is also relative. Nine out of ten Poles still describe themselves asCatholics. More than a third of the faithful regularly attend mass. Whilepriestly numbers are falling, one in four Catholic ordinations in Europe stilltake place in Poland.

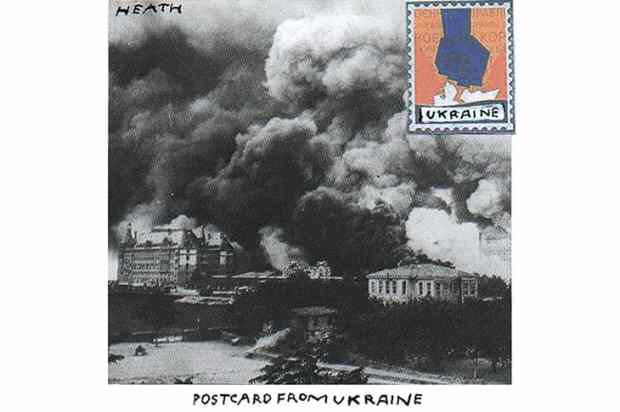

In the 20th century, the Polish church wasfortunate to be led by two spiritual giants: John Paul II and Cardinal StefanWyszyński, a figure less well-known outside Poland. During the Warsaw Uprising,Wyszyński served in an actual field hospital outside the Polish capital. Oneday, he found a piece of burning paper that had been blown from the charredruins of Warsaw. On it were the words: ‘You will love.’ He took it as aninstruction that he spent the rest of his life fulfilling.

Polish Catholics are responding with the samespirit to today’s war. In doing so, they are challenging the ‘inevitabledecline’ mentality that has gripped too many western Christians for too long.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Luke Coppen is Europe editor of the Catholic News Agency. He edited the Catholic Herald from 2004 to 2020.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in