The young woman’s screams were drowned out by the sound of drums. No older than her teens, she had been drugged and raped before being tied down and strangled by four men, while repeatedly stabbed by the older woman in charge.

This was the scene in perhaps the most famous accounts of life among the Vikings, written by a traveller and diplomat called Ahmad ibn Fadlan after his mission in 922. Sent by the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, ibn Fadlan was part of a delegation to deliver a message to the ruler of the Volga Bulghars, and along the way he had spent time with a people he called al-Rusiyyah, known to historians as the Rus’. These were the eastern Vikings who settled along the rivers flowing into the Black Sea, drawn to the riches of Constantinople and the Islamic world. He wrote extensively about a group he labelled ‘Allah’s filthiest creatures’, but the most memorable and disturbing part of his account recalls the funeral of a Rus’ chief.

The Arab traveller described how, before the funeral, the female slave had spent ten days as the dead man’s ‘bride’, attended to by servants, who were also the daughters of the woman overseeing the ceremony (whom he called the ‘Angel of Death’). On the tenth day the young woman went to each of the tents of the Rus’ warrior, having sex with all the dead man’s companions, who would then cry out that they did right by their departed friend. As the ceremony proper began, some chickens were slaughtered, a dog was cut in two, and a horse and cow were hacked to pieces, the participants all splattered with the blood of these sacrifices. And then it becomes truly horrifying.

The slave girl was lifted over a door frame where she described the paradise ahead, her jewellery was removed and she walked up to the ship where her master was buried. Ibn Fadlan recalls that she was then made to drink strong liquor, became confused and seemed reluctant to go ahead, at which point the Angel of Death grabbed her. The girl screamed as six men raped her, after which four of them killed her by strangulation, while the woman repeatedly stabbed her in the chest.

Ibn Fadlan hailed from a city of half a million people, the heart of an Islamic golden age which was heir to the civilisations of Rome, Greece and the ancient near East. It was home to the House of Wisdom, among countless other centres of learning and legal study. It would have been an immense culture shock, and his experience clearly unnerved him; at one point he was obviously agitated enough that one of the Rus’ threatened him, mocking Muslims for their funeral customs, which involve burial rather than cremation (and, quite crucially, no one gets murdered).

The Arab traveller returned safely back to civilisation, and his account would prove hugely valuable to historians, inspiring 19th-century artwork as well as 20th-century novels and films.

The scene will also be vaguely familiar to anyone who has seen The Northman, Robert Eggers’ Viking action epic, which among other aspects of Norse culture depicts ritual murder at a funeral. The film-makers were eager to make an accurate depiction of Viking society, and that society included human sacrifice.

This practice disgusted Christians and became a line of attack against their religious rivals. Adam of Bremen, writing in 1072, when paganism was on its way out, had claimed that among the pagan Scandinavians a ceremony was held where nine men (and many animals) were sacrificed every nine years. A few decades earlier his fellow German Thietmar of Merseburg described how these killings were carried out so that these men and beasts ‘should serve them in the kingdom of the dead and atone for their evil deeds’.

Historians had sometimes treated such Christian accounts with scepticism, viewing them as hostile propaganda, yet as with many old tales they have been vindicated by archaeology, with evidence of Viking human sacrifice found at Bollstanas and Birka in Sweden, Oseberg in Norway, Cernigov in Ukraine, the Isle of Man and at Repton in Derbyshire.

Thietmar and Adam were treated with scepticism because they were what we would now call culture warriors, engaged in a society-wide conflict between two moral worldviews. Their side, being linked to a wider European civilisation and far more literate, had immense advantages and would win, despite their belief in peace and male sexual restraint being so weirdly counter-intuitive. The losing polytheists had their worldview confined to history as Christianity swept across Scandinavia.

Yet today the Norsemen, or Vikings (a historically imperfect but impossibly attractive term) are themselves embroiled in a new culture war. And this time they might win, from beyond the grave.

The Northman is part of a wider Viking cultural renaissance of recent years, with The Last Kingdom, the adaptation of Bernard Cornwell’s book series; the Netflix show Vikings, as well as three Thor films, a fourth coming out this summer. Vikings are also consistently among history bestsellers, among then in the past two years Neil Price’s The Children of Ash and Elm and Cat Jarman’s River Kings.

There is something incredibly fascinating about Norse culture, with its epic tales and adventure. Their violence and brutality combines with a sophisticated culture that surprises in so many ways. Their religion feels awesome and intriguing, and it doesn’t hurt for film and television makers that Norway and Iceland contain some breathtaking scenery (nor that the British tend to find Scandinavian people beautiful).

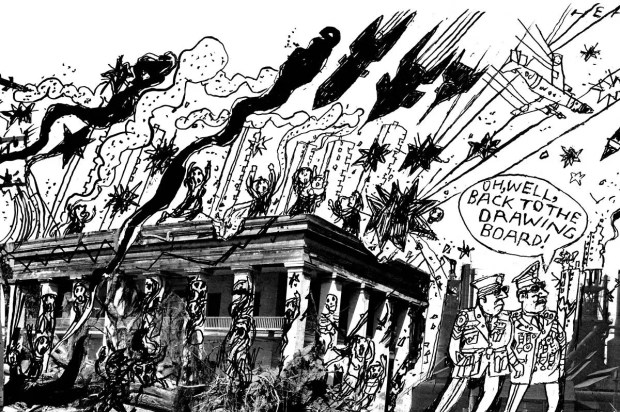

The Vikings had a huge psychological impact at the time, a terrifying spectre for people across the British Isles and coastal France, but they gained new cultural importance in the 19th century with the popularisation of the Icelandic sagas. They were attractive for a number of reasons, one of them being the raging Teutomania that found expression in Richard Wagner’s operas, but which also helped inspire the most disastrous and evil nationalist movement of all time.

But Vikings also served as perfect foil in the Victorian idea of England’s birth, and the story of its founding father Alfred the Great. From the mid-18th century, when the Thomas Arne opera Alfred was composed to celebrate the accession of George I, Alfred became the epitome of heroic rule, justice and liberty, an ideal of Christian kingship.

The fact that Alfred was tormented by sexual desires, which he prayed to God to free him from, made him all the more virtuous and relatable to Victorians. He was a hero for a pre-ironic age.

Today such an internal sexual struggle is looked down upon, seen as unhealthy and hypocritical, positively weird. English nationalism is worthy only of thralls. Christianity is so distant that police deny a dying man his Last Rites. Little surprise, then, that Alfred is portrayed rather unsympathetically in The Last Kingdom, as is Saxon Christianity generally, the protagonist Uhtred more drawn to the Vikings who adopted him. Alfred is cold and somewhat devious, even a bit odd; life with the Vikings, in contrast, might be violent, but it’s also fun: it’s top bantz. It is no surprise that author Bernard Cornwell is an outspoken atheist (and you can hardly blame him).

Alfred’s house is portrayed even less sympathetically in Vikings, his father and grandfather shown as double-crossing and hypocritical, interested only in their own gain, their religion empty and self-serving. This feels not so much a 21st century view of the 9th century as it is of the 19th, part of today’s culture war between two different visions of the world.

Vikings portrays Christian generally as fat, hypocritical and cowardly while the Norse raiders, led by the semi-mythical Ragnar Lothbrok as sexy, cool and sexually egalitarian, and this is part of recent trend for television and filmmakers to empathise more with the Vikings than their victims. Ragnar is played by a literal male model, and is accompanied by his beautiful wife who, girl boss that she is, is also involved in the fighting.

I suppose it would be pointless to pretend to be a neutral observer in this fight, because in all honesty Alfred the Great is more than just a historical figure to me. I have an almost Victorian reverence for his memory, as the father of our nation and people [a light goes off at Prevent headquarters in central London].

It was not just that he overcame great hardship, troubled by poor health and constant pain and facing an invasion of his country that at one point looked very bleak indeed. He rescued Wessex and England from foreign conquest and possible oblivion, raising men from across the shires to defeat the invaders. But he did more than that; he built cities, refounded London, and in commissioning the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle helped create the idea of England, as well as rescuing the country’s Latin Christian inheritance.

But he was also merciful to his enemies, returning hostages when in his place the Vikings would and did murder them — and that was precisely because he had a deep moral vision, stemming from his Christian faith. They were fighting a religious war and Alfred believed that when St Augustine and his Italian companions had arrived to convert his ancestors three centuries earlier, his people had been brought out of the darkness.

The battle between Christians and pagans was what we’d now call a culture war, being fought across the north of the continent. Some historians believe that Viking attacks on targets such as Lindisfarne weren’t simply driven by the attraction of an unprotected rich target, but responses to the Christian world’s attack on the northern polytheists. It is true that Christian kings and missionaries were engaged in a two-pronged drive to push north, using persuasion and force. Around the time of those first Viking attacks, Charlemagne was forcibly converting the continental Saxons, killing thousands who refused baptism.

The new religion threatened to turn the Viking world upside down, Christianity offering what Chantal Delsol called a ‘normative inversion’, a moral revolution in attitudes to life, human dignity but most of all sex. For sex was the at the heart of this early medieval cultural war, as it is with ours.

Polytheistic Norse society practised polygyny, some of its rulers noted for having several wives and dozens of concubines. The Saga of King Harald Fairhair describes how he ‘had many wives’ but ‘that he put away nine of his wives’ as a condition of one marriage. But polygamous societies are haunted by the shadow of violence. Men with no prospects of finding a mate are an inherent problem; marriage reduces testosterone levels, the main driver of violence and reckless behaviour. Unmarried men either cause trouble within a country, or go abroad and cause trouble for someone else’s. The Viking expansion may well have been related to this problem.

The new faith prohibited polygamy and much else, part of a ‘revolution that Christianity had brought to the erotic’, in Tom Holland’s words: ‘The insistence of scripture that a man and a woman, whenever they took the marital bed, were joined as Christ and his Church were joined, becoming one flesh, gave to both a rare dignity. If the wife was instructed to submit to her husband, then so equally was the husband instructed to be faithful to his wife. Here, by the standards of the age into which Christianity had been born, was an obligation that demanded an almost heroic degree of self-denial.’

No longer, as in pagan Rome, would infidelity by men be accepted; instead for Christians ‘the double standards that for so long had been a feature of marital ethics had come to be sternly patrolled.’ The sexual use of female slaves, another reality of life shown in The Northman and the universal norm in pre-Christian Europe, was now a sin.

Of course it still went on, and Charlemagne himself could compete with the best Viking rulers in the number of his concubines. A certain amount of hypocrisy was accepted with the new religion but, as with all behaviour that carries a social penalty, it steadily declined.

But to many from the mid-20th century onwards the revolution that Christianity brought to the erotic was to be lamented. Unsurprisingly, as our civilisation starts to repaganise, the Viking appeal grows, too.

Christianity brought sexual shame, both to men and women, with high-status females losing some privileges, including the right to divorce and certain sexual freedoms. The behaviour of Freyja, the goddess who represented womanhood in Norse mythology, is illustrative; she took many lovers, and is said to have slept with every elf in Asgard, without any sense of shame. To many post-Christians there is huge attraction to such a society.

Sympathetic historians point out the prejudices of sexually-frustrated medieval monks whose lack of a healthy outlet resulted in lurid fantasies about pagan behaviour, as well as misogyny. Others try to rescue the Viking legacy from the Nazis, as well as the wider political Right, and so much is made of their multiculturalism, something heavily emphasised in many recent history books. Vikings are also used as a counterweight to any claim of pure Englishness, although I’m not really sure anyone has ever really made that point, nor is the presence of early medieval raiders an argument for multiculturalism (what is unusual about England is not the absence of foreign influence during its birth pangs, but the lack of diversity after 1066 and until the 20th century).

Michael Hirst, the writer of the Vikings show, has said that ‘One of the things the series is doing is trying to overcome centuries of prejudice and ignorance about Vikings and their culture. Little Englanders and nationalists are my bête noires — I hate that! We are still Vikings, they’re embedded in our culture. It’s about time people woke up to that.’

Looking back, the moral revulsion that Christian scribes felt for the old order is not totally unlike the way that many 21st century people feel towards the moral values of the pre-1968 world: a place of sexism, racism, misogyny and homophobia, and of sexual hypocrisy. Of course, future historians will point out, it was a bit more nuanced, but there is a real battle of worldviews going on once again.

The Vikings lost the first great culture war but have managed to fight another from beyond the grave. But then, these are questions that will never be resolved and debates which will run and run — until the rooster crows telling us that Ragnarök has begun.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

This article appears in Ed West's Substack, Wrong Side of History. Subscribe here.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in