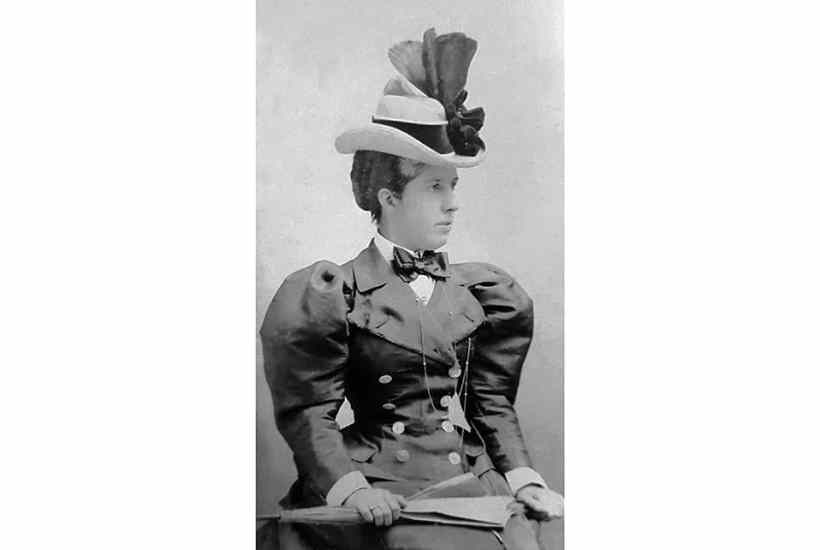

In October 1897, the grandees of the Royal Horticultural Society gathered to bestow their highest award, the Victoria Medal of Honour, struck to commemorate the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, to 60 of gardening’s greatest luminaries. For the first time, these included two women. One was Gertrude Jekyll, known by all as the Queen of Spades; the other was the 39-year-old Ellen Willmott.

But Willmott did not turn up. This public snub was the beginning of her reputation as ‘gardening’s bad girl’, as Sandra Lawrence puts it, one that increased exponentially until it exploded in stories of daffodils being booby-trapped to deter bulb thieves. By trawling through innumerable newly discovered diaries and documents, Lawrence believes she has found the reason both for Ellen’s no-show and her seeming change of personality. Thus her book, packed with detail, is one where the author’s search for information is part of the story.

It had all begun so differently. The young Ellen was popular, intelligent and lighthearted. She had a happy childhood in an affluent family of the rising Victorian middle class; from the age of seven she would come downstairs on her birthday morning to find on her plate a cheque for £1,000 (today worth £126,588) from her immensely rich godmother. Unsurprisingly, she never learned the value of money and thereafter simply bought what she wanted.

In 1876 Ellen’s father Fred acquired Warley Place, an estate 18 miles from London that consisted of a Queen Anne house, its cottages and 33 acres of land – later, much more would be added. The whole family was gardening- and dog-crazy, with seven poodles, a Newfoundland, a Pomeranian, a St Bernard and innumerable collies, corgis, sheepdogs, dachshunds and terriers. There were balls, parties, visits to London for Ellen and her younger sister Rose to take German lessons, expeditions and travel: the family went to Antwerp, Paris, Nice, Monte Carlo and, especially, the Alps, where Fred’s gout and his wife’s rheumatism seemed to improve.

Alpine gardens, which became known as rockeries, had begun to be hugely fashionable. In her early twenties, Ellen got permission from her father to create one at Warley. It would not be the usual mere heap of broken stones but a true mountain landscape. Ellen’s money poured forth to create a three-acre site of Alpine meadow, ravines, rocky cliffs, a cascading stream and a fern grotto. At the same time, she was spending ever more lavishly on clothes, hats, jewels, medieval manuscripts, ancient herbals, musical instruments and antiquities of all kinds.

Like her parents, Ellen suffered from rheumatism. By her late twenties it had become so crippling that she could no longer take part in active sports, or even dance at a ball. With Rose, she headed for Aix-les-Bains and the famous thermal treatments there. It was a very social place, with a large theatre and a gold-mosaiced casino; there were lectures, a twice-daily band in the gardens, concerts and Sunday balls ending in fireworks. As treatment had to be ongoing, the sisters decided to buy in the nearby village of Tresserve and begin creating a garden. Ellen’s beloved godmother died in 1888, leaving both her and Rose legacies worth well over £19 million today, so once again money was no object. ‘Tresserve was Ellen Willmott at play,’ says Lawrence, describing its avenues, pergolas, shady walks and plants from all over Europe.

When Robert Berkeley, the heir to the Spetchley estate, near Worcester, married Rose in a grand society wedding it left Ellen, now 33, firmly classified as a spinster and she flung herself into gardening ever more fervently. As her reputation grew, visitors to Aix began booking a ‘slot’ to see her Tresserve garden before they even left London.

Though Ellen had close platonic men friends, it was not until she met Gian Tufnell, lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Teck, the fat, jolly mother of the future Queen Mary, that she fell in love. Gian wrote:

I love you so & you must know it in the same way that I know you love me. No time to tell you more, my dear heart, except that I want you very badly. I feel so lost without you.

Then, out of the blue, Gian married the 70-year-old Lord George Mount Stephen in the Jubilee year – the same year as Ellen’s no-show at the RHS awards ceremony. It was this blow, believes Lawrence, who discovered the coincidence, that accounted for the change in Ellen’s personality from then on.

Her spending grew ever more prodigious. She now had three properties, having inherited Warley on the death of her mother in 1898 and having acquired Boccanegra in Italy, perched on a cliff with a kilometre of private beach below. She financed plant-hunting expeditions, swathed herself in jewellery and grew numerous cultivars. One of her specialities was daffodils, for which she won several gold medals at the RHS.

Eventually the money ran out and by 1907 she was borrowing heavily. The French and Italian properties went, as did the furniture, the paintings and the rare objects. She kept the jewels until last and – still very social – was always seen glittering with diamonds. She became ever more eccentric, walking home from engagements with her tiara stuffed in a brown paper bag. Stories circulated about her miserliness: she would refuse her gardeners time off for their weddings and sacked them if a weed was found in a flowerbed. She was malicious about others, once remarking of a colleague: ‘His character was as ugly as his garden.’

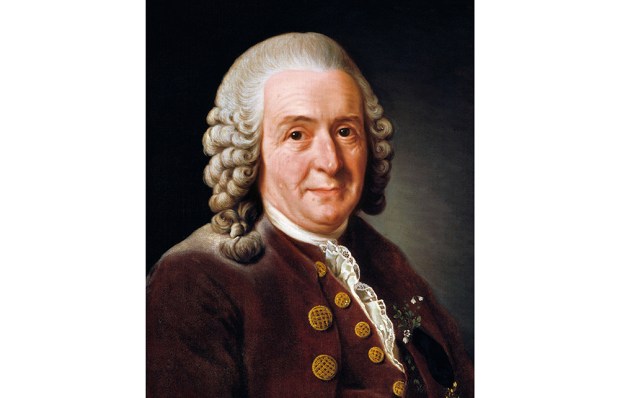

Her paranoia increased. She kept a revolver in her handbag and a brass knuckleduster in a drawer, and is said to have carried a pocketful of the seeds of a particularly invasive giant prickly sea holly, Eryngium giganteum, to sprinkle in the gardens of fellow horticulturists. So widely known did this habit become that the plant was nicknamed ‘Miss Willmott’s Ghost’.

The woman described by Gertrude Jekyll as ‘the greatest of all living woman gardeners’ died in 1934. Lawrence calls her ‘a genius as a plantswoman, a nightmare as an individual’. Both verdicts are undoubtedly correct.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in