On 19 April Wimbledon decided to ban all players from Russia, the aggressor in Ukraine, and Belarus, which let Russia use its territory as a staging post for the attacks, from this year’s tournament. The ban may reflect a desire to avoid the possibility of embarrassing the Duchess of Cambridge as the royal patron of the All England Lawn Tennis Club. In that capacity, amidst the centenary celebrations of Centre Court, Kate Middleton is expected to present trophies to the men’s and ladies’ singles winners. There was a good chance that one or both could be Russian or Belarussian, in which case video footage of the trophy presentation could be weaponised for propaganda in the still-raging war.

The spate of expulsions of Russian athletes, artists and even dead authors and composers is an ugly outbreak of neo-McCarthyism ripping through Western institutions. Wimbledon is open to charges of gross hypocrisy and might have fashioned a rod for its own back to be used by activists on any fashionable moral crusade in the future. Why were American, British and Australian players not banned unless they denounced the invasion of Iraq in 2003? Are Russian actions in Ukraine more evil than China’s vis-a-vis the Uighurs? What of countries that execute homosexuals or condemn women to inferior status? The precedent has been set by the world’s most prestigious tennis tournament that even in competitions that feature athletes playing as individuals and not for their nation (as in the Olympics or the Davis Cup), regardless of where they reside (Victoria Azarenka has lived in the US since her teens), they can be banned for the sins of their governments. Of course, it also devalues the tournament. On current world rankings the ban will exclude more than twenty eligible players from the ladies and gentlemen’s (isn’t it nice that Wimbledon has stuck to this traditional language) singles competitions. On 10 May, the world’s leading men’s players called for ranking points to be withdrawn from Wimbledon in protest at the ban.

Wimbledon’s ban is a microcosm of the pathologies that afflict international sanctions. They expand the toolkit of powerful countries to impose their values and policy priorities on the rest and thereby build resentment in the latter who see hypocrisy where sanctions-imposing countries profess moral virtue. It’s proven extremely challenging to secure and sustain universal compliance with sanctions regimes. In a world of scarcity where costs and benefits are unevenly distributed, there will always be a market clearing price for every good. Three months into the war, even the BBC has woken up to the realisation that vast parts of the non-Western world do not share the West’s one-sided anti-Russian narrative. Whether based in economic and military self-interests or in perceptions of Western hypocrisy, double standards and colonial past, many countries have refused to join Western condemnations and sanctions.

In a CNN commentary, Jeffrey Sachs estimates that the 100 countries in the UN General Assembly that did not vote to suspend Russia from the Human Rights Council account for 76 per cent of the world’s population. Energy price rises owing to sanctions are an inconvenience to Europeans. It’s a particularly perverse form of selfish arrogance to demand that India, for example, should eschew the purchase of discounted Russian oil when steep ptice rises in essential energy will cause significant hardship for millions of poor Indians.

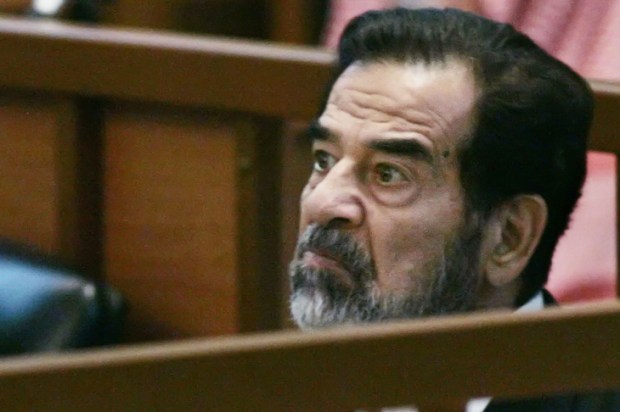

As this suggests, the impact of sanctions is disproportionately harsh on innocent victims. A starkly graphic example of this was sanctions imposed on Saddam Hussein after the Gulf War, estimated by the Food and Agriculture Organisation to have caused 576,000 child deaths by mid-1994. Child mortality rate jumped from 56 to 131 deaths per 100,000 births from 1984–89 to 1994–99, according to Unicef which attributed 500,000 child deaths directly to sanctions. That experience did a lot to discredit sanctions as a supposedly humane alternative to war for dealing with rogue regimes. It also led directly to the oil-for-food scandal in which Australia was so badly implicated. In his annual report on the UN’s work in 1998, Secretary-General Kofi Annan acknowledged that ‘humanitarian and human rights policy goals cannot easily be reconciled with those of a sanctions regime’. Sanctions create shortages and raise prices in conditions of scarcity.

The poor suffer; the middle class, essential to building the foundations of democracy, shrinks; the ruling class extracts fatter rents from monopoly controls over the illicit trade in banned goods. The evidence shows that time and again, family cliques surrounding dictators monopolise the black market spawned by sanctions and the resulting scarcities and shortages of goods in the open market. Sanctions also offer an easy scapegoat for ruinous economic policies. Economic pain is simply blamed on hostile and ill-intentioned foreigners. Bearing pain is portrayed as the patriotic duty of every citizen, and dissent silenced or liquidated.

There is the further pathology of mission creep and mutation. Like race-based affirmative action, gender equality and cancel culture, once introduced for one target group or goal, they are appropriated by others for additional groups and causes that are also pursued with proselytising zeal, meaning that opponents are not just inconvenient obstacles but positively evil. Therefore they are deserving of vilification, dehumanisation and punishment. And so it is that some experts and officials are already calling for countries that fail to cooperate with the WHO during a pandemic to be hit with prompt sanctions under a new pandemic treaty. Presumably this means that Sweden and Florida, among a handful of jurisdictions to have got their Covid policy settings right while all others raced to the bottom of panicked stupidity, would have been subjected to international sanctions. And we can safely predict that laggards in the global Net Zero race to the economic bottom would be early candidates for punitive sanctions.

More often than not, sanctions are morally dubious, ineffective and can be counterproductive, prompting a successful search for self-reliance or alternative suppliers for critical goods. They damage the economic interests of those imposing sanctions, including undermining reliability as a supplier and, in this case, risking the de-dollarisation of the world economy as others invest in the creation of parallel financial systems and institutions that are less vulnerable to capricious strikes by the dominant West. The rouble fell to begin with but since March 10, it has more than doubled in value against the euro, dollar and pound. Often they damage relations with allies and friends without securing the intended objectives against target regimes. All in all, therefore, sanctions are a poor alibi for and not a sound component of good foreign policy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in