Eighty years ago, just after midnight on 28 March 1942, the British destroyer HMS Campbeltown crept up the estuary of the River Loire towards the heavily defended port of St Nazaire. Here lay an immense dry dock, the only facility on the west coast of France that German battleships such as the ferocious Tirpitz could use if they needed repair. Destroy the dock, and Tirpitz would be unable to sortie against the Atlantic convoys supplying Britain. The only way to do that, however, was to wreck the lock gate at the entrance. And that meant filling a ship with explosives, ramming it into the gate and blowing the whole lot up, while commandos jumped ashore to demolish the pumps, the winding gear and anything else they could.

That was the mission, codenamed Chariot, of the 623 sailors and commandos on board Campbeltown and the flotilla of motor launches she led. It is their story that Giles Whittell tells. It is not a new one: it has been the subject of two feature films, a slew of books, including an excellent recent one by Robert Lyman, and an engaging Jeremy Clarkson television documentary. Even the Greatest Raid title has been used before. Nonetheless, it is a story of extraordinary courage that does not get stale. Even if everything went right and the raiders somehow managed to sneak past the German defence batteries into St Nazaire and destroy their targets, they would have to fight their way back to the boats through the docks, in the teeth of fierce opposition, before running a six-mile gauntlet of enemy coastal batteries to reach the open sea. Few of those who set out could ever have expected to come home. Most of them did not.

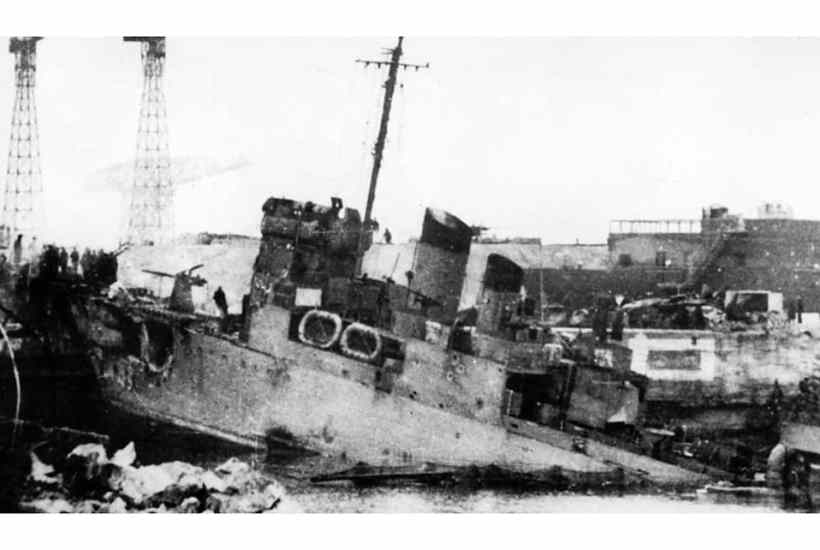

Campbeltown was still almost a mile from the dock gates when the alarm went off and the night exploded as German gunfire swept the harbour. In the chaos, she rammed the caisson as planned and some of her commandos managed to get off and plant their demolition charges. Most of the motor launches were sunk or blown up even before their commandos could reach dry land, however, so no boats survived to evacuate the landing party. Not one man who went ashore got back to Britain by sea. The surviving commandos, many of them wounded, tried to break out of the town in the dark, but by morning most had been rounded up and taken prisoner. A handful ended their war in Colditz, while five lucky commandos, helped by the brave men and women of the Resistance, walked the 350 miles to neutral Spain and eventually made it home that way.

Later that day, the three tons of explosive hidden inside Campbeltown finally went up, destroying the dock gate. Chariot had achieved its main military objective, but the human cost was heavy. Some 16 French civilians died during or soon after the raid and probably more than 300 Germans were killed. Of the 623 British sailors and soldiers who went to St Nazaire, 169 died, 213 were captured, and just 234 returned to Britain. Five men received the Victoria Cross for valour, two of them posthumously. The only other second world war operation to see so many VCs won was the much later and longer battle of Arnhem in 1944.

The St Nazaire raid was about more than destroying a dry dock, however. It was also designed to prove that ‘butcher and bolt’ raids on the enemy-held coast were a good use of resources, and especially of élite manpower, and to disarm the many doubters and critics of the chief of Combined Operations, Lord Mountbatten. Without Chariot there might have been no further raids such as the much larger, and ultimately disastrous, attack on Dieppe five months later.

More importantly, the St Nazaire raid was intended to show Britain’s allies, enemies and indeed her own people that she was not finished yet. It is easy now to forget how poorly Britain’s war seemed to be going in early 1942. After two years of non-stop defeats and disasters, the rampages of the Axis powers across the globe appeared unstoppable. The USSR seemed likely to be forced out of the war before the USA could get into it, and Singapore’s tame surrender a few weeks earlier had made it look as if British troops could not, and perhaps would not, fight. Chariot was as much a media event as an operation of war, designed to capture the headlines. It worked: ‘Splendid success: scene of blazing destruction,’ trumpeted the Timesthe next day. The world of communications and spin is one which Whittell, himself an experienced journalist, knows well; and this is the section of his book that sings, even as it reminds us that war is always, as Clausewitz famously wrote, a deeply political act.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in