With the passing of Sir Harrison Birtwistle last month we are witness to a changing of the guard in new classical music. For 70-odd years contemporary music in the West was dominated by a highly exclusive atonal mode of thought that produced works that were hostile to the wider music-loving public and written for a small but highly subsidised cultural circle.

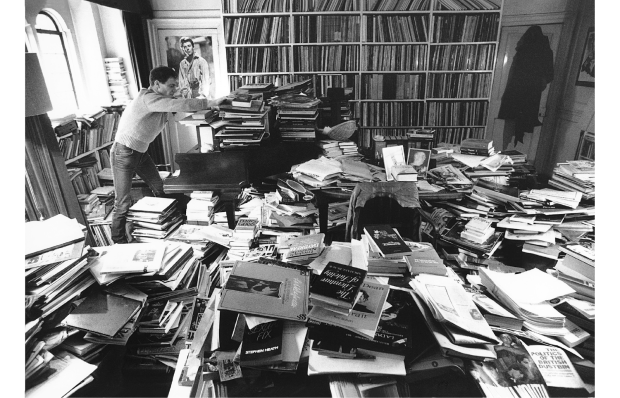

If it was spontaneous when it began, the atonal idiom – meaning a highly dissonant style – quickly ossified into a kind of luxury backwater of music, so obscure it couldn’t even be questioned, yet endlessly backed by public subsidy which the public could nevertheless never challenge. It became an immovable impediment to other musical idioms that might better serve the public and retain an audience in the broader sense.

Seeing this deeply ingrained problem for what it was, by the early 1990s a small group of like-minded composers and music lovers (of which I was one) – people who wanted to see a more open landscape in which the naturally melodious and harmonious instincts of music creators could once again be permitted to operate – got together and began to ask what could be done.

We were facing a political problem as much as a musical one. The issue was not that atonal music was being written and played; I would defend the right of anyone to express themselves musically exactly as they wish. It was a political problem in that an entire, lavishly subsidised establishment arose around this culture, who – quite frankly – had their snouts in a deep trough of public money and had no incentive whatever for anything to change.

The answer seemed to be to shine a light, to raise debate and to gain attention for alternative paths forward for new classical music; in other words, to open up the field, let daylight in and allow the profound need for music of the heart to once again be allowed to be served.

But how to do this? On a train bound for London in early 1994, with several allies, the conversation turned to mounting some sort of peaceful direct action or civil disobedience. What else could provide the necessary spotlight on the matter? It would have to be something that would gain national attention – not just a worthy article in some specialist journal.

What followed was a random but seemingly fortuitous sequence of spontaneous events. A tiny ad appeared in The Spectator inviting people to join ‘The Hecklers’ – named after the 18th-century debating society. This was quickly followed by an article in the Times highlighting the idea and surmising the formation of a group who would boo modernist music.

All of this had been instigated by one of our initial number going out on a limb. At this point alarm bells began to ring. If this group were planning to boo performances I could foresee how easily all of this could backfire. We would be portrayed as young fogey reactionaries shouting down daring, innovative music. We could be seen as fascistic oppressors of radicalism, whereas in fact the purpose would be to decry a lack of freedom under an aesthetic dictatorship and be champions of free speech.

From my perspective what I was about as a composer was the very reverse of censorship. In my belief tonality is a universal that underpins all music – including so-called atonal music. And as day follows night, so the time has come that the flame of radicalism has passed back to composers who now write in a romantic and emotional style again, but one that is at the same time entirely contemporary. So we were ahead of the curve calling out the endgame of a style that had dominated European music for nearly a century. It was atonalism that was the reactionary establishment – the oppressor – and we, the new tonalists, who were the revolutionaries.

But how to convey this, knowing our enemies would do anything they could to taint us?

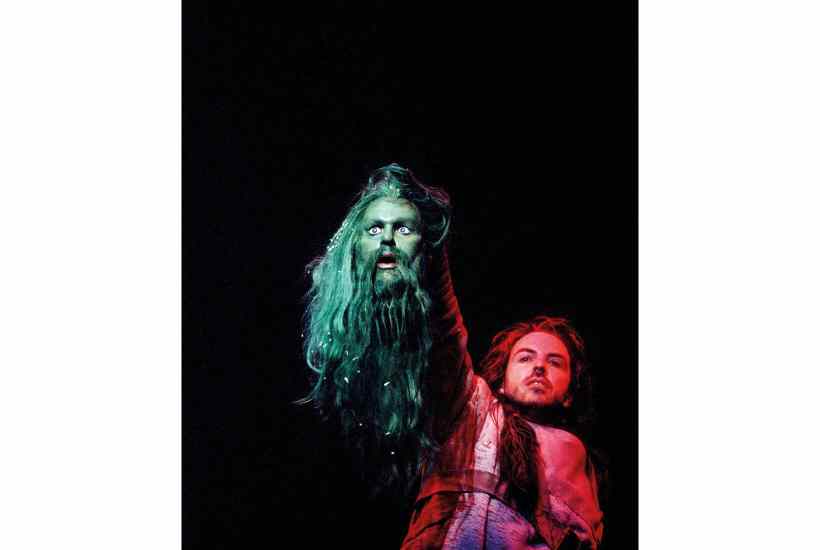

I formed a group called the Romantic Futurists and informed the press that we would boo Birtwistle’s new opera Gawain at the Royal Opera House. Newsnight made a film about us. Having done so they then lined us up – we were mostly in our twenties or early thirties – and said: ‘We’ve spent £20,000 making this film, now you better bloody boo!’ It was a life lesson on how the mainstream media operates but we were undeterred.

And so the big night arrived. Taking part in such a demonstration was not something that came naturally to me. I was a classically trained musician from birth and quiet by nature. Both my parents were orchestral violinists – my father was in the Royal Opera House orchestra – and I was beginning to make headway as a composer myself. As I entered the auditorium of the Royal Opera House my heart was beating fast. By then I knew that a fair range of the media were interested and in attendance. Jeremy Paxman was waiting to conduct an interview with us afterwards. A number of indignant members of the arts establishment had rolled up to counter cheer: Lord Gowrie, Natalie Wheen and Alfred Brendel, no less.

The growling, grinding, thumping score rolled on its slow, monumental way. I should make clear that I have nothing against Birtwistle. I’ve conducted his music. Sonically, it works. But it’s cold, even among atonal music. And in this case it was the necessary iconic exemplar in the iconic institution.

About 20 people were dotted about the auditorium and I had had little or no control over who they were or what they might do. In the brief silence between the end of the performance and the start of applause, a young woman could very clearly be heard shouting: ‘Shame about the score!’ Then came applause; then a cat-call of booing slowly erupted clearly among the counter applause; then a bit of cheering. The hollering by us was later described in the press as a ‘weak English booing’.

All hell broke loose as we exited – a pandemonium of media, cameras and shouty arguments. A Telegraph journalist interviewing me was grabbed by Natalie Wheen and dragged away with the words, ‘Come this way and talk to someone serious, come and talk to Lord Gowrie.’

A confrontation between us and some young Birtwistle supporters was captured by The House, the notorious fly-on-the-wall doc about the Royal Opera House. It’s good-humoured stuff but I was uncomfortable with one of our party shouting ‘down with modernism’, as in my view we were the modernists.

A whole stream of articles and coverage followed. And it gave Birtwistle the most publicity he had ever had. Since then, slowly but surely, the stranglehold of atonalism over music culture has relented. The younger generation of composers have become much more open-minded, without the need to fight the culture wars of the past.

Ultimately, however, the issue was not about me or Birtwistle. What was at stake back then was far more consequential than any one individual, and had to do with the very freedom for music to serve the wider world. Of course through film music, pop and rock, it had continued to do so unimpeded. But for those of us who cared about the classical tradition, and regard it as one of the greatest expressions of the human spirit, the emancipation from the ivory tower of atonalism couldn’t come too soon.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in