When Russian forces first rolled into Ukraine, most thought that President Zelensky would have to flee. Boris Johnson said Britain could host a Ukrainian government in exile. The Americans offered to get Zelensky out of Kyiv to protect him from the hit squads that Moscow had sent to kill or capture him. Zelensky, with the courage and flair that has defined his war leadership, replied: ‘I need ammunition, not a ride.’ Well, the Ukrainians now have the ammunition – and three months in, the war looks very different to how on 24 February anyone imagined it would.

Yes, the Russians have taken Mariupol, opening the way for a land corridor from the Donbas to Crimea, which they annexed in 2014. But having won the battle for Kyiv, the Ukrainians are now driving the Russians away from Kharkiv and frustrating Putin’s forces in the east.

With western arms flooding into Ukraine (ten planes bringing military aid arrived in Ukraine at the start of this week), there is now a chance to go on the offensive. There is $40 billion of US aid on the way. That sum alone is more than the entire Australian defence budget. It means that Ukraine can now aim to retake territory rather than just frustrate the Russian advance.

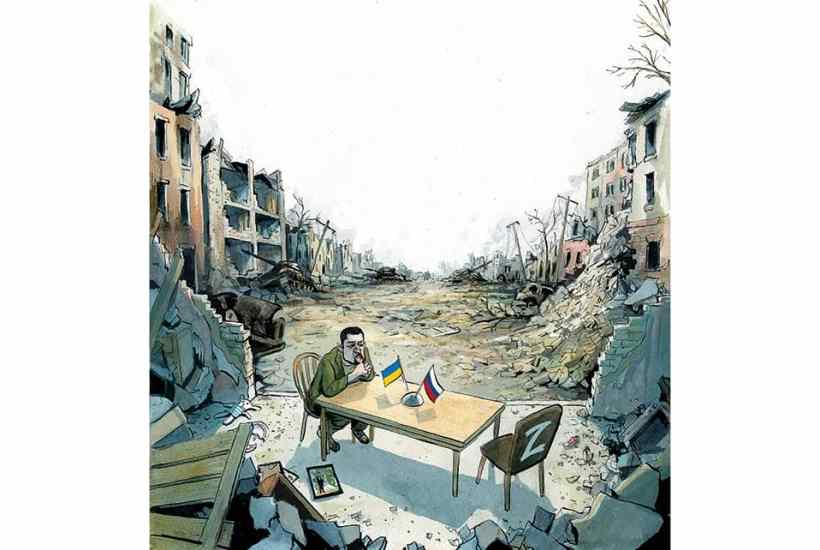

This turn of events raises questions. What should Ukraine’s war aims be? Should they try to push the Russians back to where they were before the invasion – or keep fighting, hold out for Crimea, and attempt to undo all the losses they have suffered since 2014? Should Zelensky be prepared to talk terms with Putin despite the appalling crimes committed by Russian forces? And should Putin be offered some kind of face-saving exit?

Putin’s decision to launch a full-scale invasion and the bravery with which the Ukrainians resisted it has brought the West together. The invasion snapped Nato out of its torpor and the alliance is now expanding, its purpose clear. The G7 has created a new role for itself as a vehicle for coordinating sanctions between the US, the EU, other western economies and the east Asian democracies.

In recent days, this united front has cracked a little. Macron has said that Putin should not be humiliated, while Zelensky has told Italian TV ‘We won’t help Putin save face by paying with our territory.’ Paris has denied that this is what the French President was suggesting, yet it’s clear that he is thinking about how to build new security balances in Europe that factor in Russia.

At the same time, EU firms are now being allowed effectively to pay for their Russian gas in roubles – something that the Commission, which is more hawkish than several of the member states, initially implied would be against the sanctions regime. In Whitehall, influential figures complain about a ‘lot of sliding on the sanctions side’. One British cabinet minister says that the EU ‘will never cut off’ Russian gas. Volkswagen is calling for a return to business as usual with Russia as quickly as possible. So the split is between the more hawkish states, led by the Poles and the Balts, and the French and Germans.

Real negotiations to end the war remain a distant prospect. Any talks that have taken place have been perfunctory. ‘The Russians are nowhere near the negotiating table,’ says one well-placed British source. The capture of Mariupol opens up for Putin the possibility of denying Ukraine freedom of navigation in the Black Sea – which would make it harder for it to function economically as a state. Russia will only be open to negotiation if it loses its recently acquired land corridor to a Ukrainian counter-offensive.

But it is nevertheless significant that the Foreign Office now has a negotiations unit who are coordinating with allies and prepping for what may happen in the medium-term. Peace talks aren’t out of the question. One diplomatic source describes the British position in this way: ‘To be hard on Russia and put Ukraine in the strongest negotiating position.’

There are several parts to this. The first priority is maintaining the sanctions pressure on Russia, which London would like to intensify with a full oil and gas embargo. Second is to continue supplying Ukraine with the weaponry that enables it to change the facts on the ground.

‘We’re helping them come to the negotiating table from a position of strength. What they do with that strength is up to them,’ says one Whitehall source, who goes on to add: ‘The Ukrainians will not do anything without the UK and the US in the room.’

This is a reference to the post-2014 peace talks, the so-called ‘Minsk 2’, when the Russians suffered little for their aggression and the French and Germans took the lead on the peace deal. ‘For that to happen again would be a disaster,’ says a government minister. ‘We cannot allow Putin to re-arm and return.’ The British favour a ceasefire, but only if the Russians withdraw to where they were before the February invasion – at the very least. A ceasefire simply to enable negotiations would be seen in London as a mistake now. ‘Zelensky’s forces have forward momentum, he is not going to want to stop now.’ The idea of allowing Putin some territorial concession is also dismissed: ‘America and Britain are not in that space.’

The more difficult question is what to do about Crimea. The Russians annexed the territory in 2014 and have incorporated it into their own country, but the western world does not recognise this redrawing of inter-national borders by force. Some in the security establishment think Zelensky should keep fighting to get Russia out of Crimea: not because the aim is realistic, but because it would bog Russia down and stop them from recovering and re-arming. But realistically, if Ukraine used western equipment to move into Crimea and retake territory that Russia now claims to be part of its own country, the escalatory risk would be clear.

For now, the UK government is, in the words of one Johnson confidant, content to ‘take our cue’ from Zelensky. (There are some mutterings in Whitehall that in their eagerness to see the Russians defeated, the Poles are in danger of trying to dictate to Kyiv what its war aims should be.) Another

senior British figure says ‘You can’t be more Ukrainian than the Ukrainians’, and it is thought that Zelensky is prepared to negotiate on Crimea, even if other members of his government take a more hardline stance.

In London, the sense is that if the Ukrainians can assume control of the water supply from Ukraine to Crimea, by retaking the north Crimea canal, that will force Putin to the negotiating table. This is a more subtle position than the suggestion by some ministers that Russia should be pushed out of Crimea by force if necessary.

Putin likes to leave chaos behind after an invasion: the so-called ‘frozen conflicts’ which never end are intended to provide a reason for him to restart hostilities if it suits him. His original plan for Ukraine was to create a pretext for invading by claiming a provocation in the two self-declared republics in the Donbas. That plan was thwarted by western intelligence, which issued warnings about the invasion. His aim now will be to occupy eastern Ukraine and ensure unrest.

So Ukraine’s future military capabilities are crucial. Realistically, the country is not going to join Nato – states with outstanding territorial disputes are not permitted to join the alliance, and too many members think it would be too provocative to Russia to admit Ukraine. (It is worth noting, however, that some influential figures in the Ukrainian government are privately critical of Zelensky for accepting that Nato membership is not realistic.)

What Britain wants is for Kyiv’s military to be built up to Nato standards, so Russia could not hope to win a conflict by conventional (i.e. non-nuclear) means. As one source who has discussed the matter with Johnson puts it: ‘It is tooling them up to protect themselves – that is the future for Ukraine. We’ll make sure they are tooled up with intelligence, weapons and training so they are unconquerable.’ Poland and the Baltic states share this aim.

Next comes the question of what relations with Putin will look like post-Ukraine. Macron’s willingness to maintain direct lines of communication with the Russian President is not something London is prepared to do. ‘The sight of anyone negotiating with Putin despite what he’s doing is difficult to stomach, however honourable his motives are,’ says one ally of the Prime Minister. The No. 10 view is that ‘it’s really hard to imagine going back to any resemblance of a normal relationship with him’.

The sanctions on Russia are unprecedented: a G20 economy is effectively being cut out of the world economy. But they are inevitably causing pain to the countries which are levying them. If a peace deal were to be agreed, there would be pressure to lift them. Yet the British government’s view is that the rapid removal of sanctions would be a mistake: ‘Rather than lift the sanctions and live happily ever after, we would want to use them as leverage to secure reparations,’ says this source. So the British favour lifting them only in part, with the option of snapping back at the first sight of any Russian aggression. The idea is that this would help deter any future Russian revanchism.

In private, senior figures in the UK government insist that relations with Russia should never be the same again. They argue that the dependence on Russian gas by Germany and other European countries should be ended, and question the wisdom of allowing again the exportation of crucial bits of technology to Russia. If, as the US defence secretary Lloyd Austin has said, you want to stop Russia from being able to do this kind of thing again, why would you send it what it needs for advanced manufacturing?

When Ronald Reagan was asked what his policy on the Cold War was in 1977, he replied: ‘We win, they lose.’ Reagan was vindicated; but struggles rarely end so simply. However morally right it would be for Putin and the Russian leadership to be tried for war crimes, that is not going to happen. Instead, the West should focus on sending Zelensky into the negotiating chamber in the strongest possible position. If Ukraine repels Putin’s invasion and if after that it continues to be equipped to do so again, that would be the best achievable outcome to the war.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in