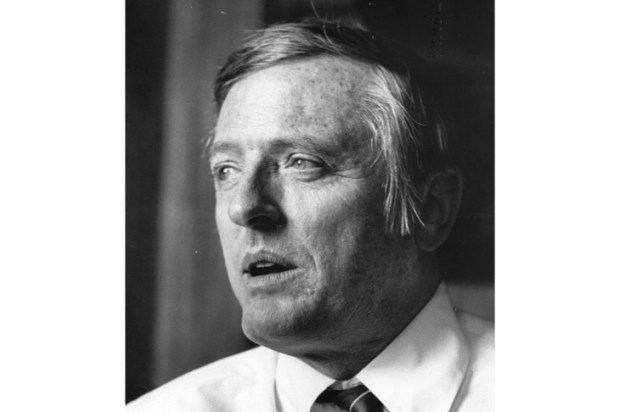

It was sad to see Ray Liotta, that magnificent actor, had died the other week. He was most famous for doing Goodfellas, Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece about rough common or garden gangsters rather than those princes of iniquity in Coppola’s Godfather trilogy. Liotta’s performance in Goodfellas is about as good as film acting gets and he absolutely holds his own with Robert DeNiro and Joe Pesci if he doesn’t in fact act them off the screen. The story goes that DeNiro didn’t exhibit much warmth to Liotta which is a pity if it’s true because Ray Liotta was a natural-born star with Tony Curtis-style good looks who also had the weight and seriousness of an actor of the first rank.

That’s written all over Something Wild, that Jonathan Demme film in which he’s paired with that underrated ditzy blonde Melanie Griffith, and the firepower of her brilliant comic timing and his bewilderment is a wonder to behold, a glory of comic and romantic comedy electricity.

Ray Liotta was an abandoned baby who made his way from doing musicals at the University of Miami to Hollywood.

And if you want to see him in a big-time, old-style, free-to-air bit of television at its most exorbitantly enriched have a look at him in the weird policier Shades of Blue where his co-star is Jennifer Lopez. In this far-fetched but engrossing story of double-dealing and betrayal JLo swoops and rolls her eyes and twirls her body like the sumptuous star she is. But Ray Liotta acts with the fierce embattled dignity of an actor who could play Willy Loman or any of the great roles in the classic American repertoire. He was a prince of an actor and we are diminished by his loss.

It was cheering, given this, that the Astor – who did Pasolini proud with their contextualising retrospective, putting that complex director’s work next to Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris, for instance – have shown a number of Liotta’s films as a memorial to this ‘great one gone’. It’s good to see independent cinemas being downright custodial in this way. If this is a reaction to the attritions of Covid and lockdown it’s a fine footnote to that grim moment.

If custodianship is your caper and if you have been hungering for a really big-time art show you won’t be able to go past the Picasso Century at the National Gallery of Victoria which not only includes a great cavalcade of works by Pablo Picasso, the most towering of all twentieth-century painters, but also complements his work with that of the widest range of his contemporaries from the poet Apollinaire (the man who demonstrated with a stroke of his pen that poetic symbolisme was not over) to the excruciated intensity of Francis Bacon and the very opposite to Picasso tranquillity of his great contemporary Matisse.

The work of Picasso is an alternate world, rivalling and usurping reality: the Rose period, the Blue period, Cubism, the great signature works like ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ and ‘Guernica’, that image of the desolation and horror of war rivalling Goya.

And then there’s the fact that Picasso was such a walking instantiation of the Great Painter that he also seems to have imitated himself and at least on occasions sold his genius out by decoratively toying with his own mannerisms.

In any case the great critical work which puts this particular reservation with the greatest possible cogency and force is John Berger’s The Success and Failure of Pablo Picasso. Berger is a profoundly moral and hence traditional critic and to read him weighing into Picasso while also having a sense of his genuine greatness is an education in aesthetics and the importance of a sense of value.

It’s an interesting coincidence that in the new novel by Geraldine Brooks, Horse – the story of a great racehorse in the antebellum American South – the heroine, an Australian scientist who puts together bones, is dismissive of Berger and her black lover, an art historian, explains to her why she’s wrong.

Beyond this, of course, all sorts of people these days are liable to clamour for the cancellation of Picasso because of his rampant sexuality though it’s hard not to think the greatness of the art will have the last word.

Then again, there are the traditionalists who hate modernism. Was it the poet Philip Larkin who said the respective careers of James Joyce, Pablo Picasso and Charlie Parker showed the falling off of three great talents as they developed? (No prizes for guessing the odd man out but who could begrudge Larkin his love of jazz?)

The other week a film by a much-attacked director Woody Allen, an all-but-unknown film from 2008 Cassandra’s Dream proved dark and compelling. It stars Colin Farrell and Ewan McGregor. And McGregor is a reminder that Virginia Gay’s Cyrano is finally to hit Melbourne. It’s a musical and a lesbian re-write with a happy ending but Gay saw McGregor do that most poignant of swashbuckling French tragicomic dramas and that lit the torch for her.

We associate the role of Cyrano in Rostand’s original play with the sort of actor who plays Falstaff or Iago rather than Hamlet. This is certainly true of Ralph Richardson (the most highly regarded of all Falstaffs) and José Ferrer who was a very snaky New York-accented Iago to Paul Robeson’s Othello. It’s not true of Gerard Depardieu in the French film of Cyrano. Gay who is famous for playing Calamity Jane has turned the story on its head but it’s hard not to believe that great things will come out of this. She and her director Sarah Goodes had the heartbreaking experience of having their Cyrano close on the opening night. It’s the most ghastly instance of what happened to the theatre in Daniel Andrews’ Melbourne. Now the theatres are buzzing again and as people confront an embarrassment of riches a lot of theatre-goers in the know are going to opt for Gay’s transformation of a famous work. She has a sweeping vision and an infectious enthusiasm for the glory of the masterpiece she is tinkering with.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in